FROM adulterous, gun-running missionaries to rapist farmers and disgruntled soldiers, Nigel Penn’s Murderers, Miscreants and Mutineers: Early Cape Colonial Lives is as fascinating as the characters it depicts are disappointing.

"SA is a violent society, in a sense I am trying to explore the roots of that violence," says Penn.

Following on from 1999’s Rogues, Rebels and Runaways, this is the fifth book (two are co-authored) from this University of Cape Town (UCT) historian. That he has won the UCT Book Award three times, and a Choice Award from the American Library Association in 2007, comes as no surprise — his prose is full of meticulous detail and wry humour. For some, the detail will be too much, others will revel in it as much as he does, and Penn’s prose is often entertaining.

...

MURDERERS, Miscreants and Mutineers uses pre-trial records to reveal this detail. This, says Penn, means "my source leads me to the violence". It also leads him to vignettes about daily life that disclose surprising detail down to hair colour or manner of dress.

A prime example is that of the gun-running missionary Johannes Seidenfaden, who is described as "a little laughing round-headed German". Records show Seidenfaden persuaded another man’s wife to trade her body to him for his teaching her how to read the Bible, a delightful bit of hypocrisy from a man of the cloth. "Yes, he was the worst missionary who ever preached the gospel," says Penn. He was a gun-runner, an adulterer, a racist and very exploitative … by telling his story I can reveal the colonial attitudes to interracial marriage, and how far equality extended to Christians of another colour, also the role of religion in colonial society."

It is these threads — attitudes to sex, women, social status, religion, people of other creeds — that make this book a gripping read. "It shows one the rich, complex roots of our society. It illustrates that there was a great deal of interracial mixing and a degree of fluidity between groups, which apartheid tried to stop."

...

PENN notes that the national archive holds few colonial-era diaries as many people of all colours were illiterate. He perused them looking for the "voices" of people who were not usually heard — soldiers, slaves, women, the Khoisan.

"So, using the clues that come (from pre-trial records), I try to elaborate on the context, try to rescue historical characters from the obscurity of history," he says.

Status, he says, was "even more important than race" in the early colonial Cape. It was quite precarious, so it had to be defended at all costs — a social set-up that mirrored Europe at the same time, where "men would quite often resort to violence" to defend their honour.

This, however, is not to say that all races were on an equal footing. The sad story of the 1727 rape of a Khoikhoi woman by a farm manager shows this. Despite there being several witnesses to parts of Theunis Roelofsz’s rape of the "elderly" Khoikhoi woman Crebis, the crime did not go to court. Neither did his murder of her son Casper.

"The trouble was that all the evidence linking Roelofsz to Casper’s death came from the slaves, whose word, by law, had no validity when placed against the word of a Christian or a free-born man.... As for Crebis’s testimony, although she was free-born, she was a heathen and, moreover, had been drunk at the time."

Penn’s books are all exercises in "microhistory", focusing on an individual or an event to draw a picture of the cultural context. "Detail is important, it gives insight into what was happening around them. Landscape is important too. The stories are very much situated in the landscape of the Cape interior."

...

THE importance of landscape is beautifully illustrated in the story of Maria Mouton, married at the age of 16 to a free burgher, "Schurfde Frans" (Rough Frans), and the only woman in the 18th century to be executed at the Cape. Mouton was executed for inciting her slave lover to murder Frans in the horseshoe-shaped valley of the Land van Waveren (Tulbagh). Penn’s telling of the story shows how she might easily have got away with it for longer because of the farm’s isolation.

Penn first pored through the national archives when he was looking into "what happened to the Khoi in the 18th century" for his doctorate. It was a time he describes as "the vital years of their destiny".

"It was hard to master the VOC (Dutch East India Company) archive for the 18th century," he says. "I had very elementary Afrikaans and (the records) are in 18th century Dutch. It took about 10 years."

After gaining his doctorate in history, Penn continued his research, relying heavily on the criminal records, and some trips to archaeological sites, looking into Khoikhoi lifestyles.

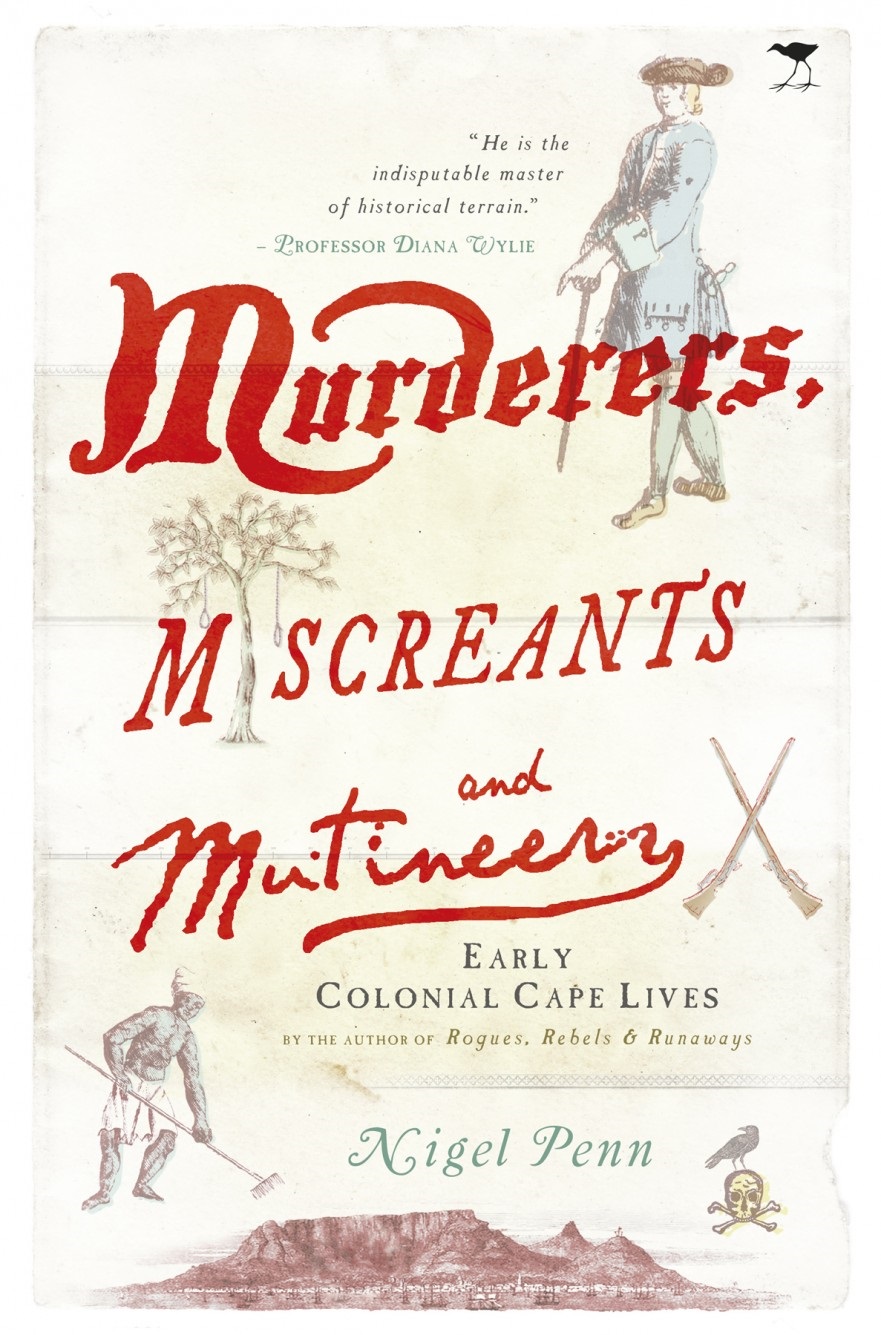

Nigel Penn has written a sequel to Rogues, Rebels and Runaways, focusing on the less salubrious side of life in the Cape in the 18th century. Picture: SUPPLIED

FROM adulterous, gun-running missionaries to rapist farmers and disgruntled soldiers, Nigel Penn’s Murderers, Miscreants and Mutineers: Early Cape Colonial Lives is as fascinating as the characters it depicts are disappointing.

"SA is a violent society, in a sense I am trying to explore the roots of that violence," says Penn.

Following on from 1999’s Rogues, Rebels and Runaways, this is the fifth book (two are co-authored) from this University of Cape Town (UCT) historian. That he has won the UCT Book Award three times, and a Choice Award from the American Library Association in 2007, comes as no surprise — his prose is full of meticulous detail and wry humour. For some, the detail will be too much, others will revel in it as much as he does, and Penn’s prose is often entertaining.

...

MURDERERS, Miscreants and Mutineers uses pre-trial records to reveal this detail. This, says Penn, means "my source leads me to the violence". It also leads him to vignettes about daily life that disclose surprising detail down to hair colour or manner of dress.

A prime example is that of the gun-running missionary Johannes Seidenfaden, who is described as "a little laughing round-headed German". Records show Seidenfaden persuaded another man’s wife to trade her body to him for his teaching her how to read the Bible, a delightful bit of hypocrisy from a man of the cloth. "Yes, he was the worst missionary who ever preached the gospel," says Penn. He was a gun-runner, an adulterer, a racist and very exploitative … by telling his story I can reveal the colonial attitudes to interracial marriage, and how far equality extended to Christians of another colour, also the role of religion in colonial society."

It is these threads — attitudes to sex, women, social status, religion, people of other creeds — that make this book a gripping read. "It shows one the rich, complex roots of our society. It illustrates that there was a great deal of interracial mixing and a degree of fluidity between groups, which apartheid tried to stop."

...

PENN notes that the national archive holds few colonial-era diaries as many people of all colours were illiterate. He perused them looking for the "voices" of people who were not usually heard — soldiers, slaves, women, the Khoisan.

"So, using the clues that come (from pre-trial records), I try to elaborate on the context, try to rescue historical characters from the obscurity of history," he says.

Status, he says, was "even more important than race" in the early colonial Cape. It was quite precarious, so it had to be defended at all costs — a social set-up that mirrored Europe at the same time, where "men would quite often resort to violence" to defend their honour.

This, however, is not to say that all races were on an equal footing. The sad story of the 1727 rape of a Khoikhoi woman by a farm manager shows this. Despite there being several witnesses to parts of Theunis Roelofsz’s rape of the "elderly" Khoikhoi woman Crebis, the crime did not go to court. Neither did his murder of her son Casper.

"The trouble was that all the evidence linking Roelofsz to Casper’s death came from the slaves, whose word, by law, had no validity when placed against the word of a Christian or a free-born man.... As for Crebis’s testimony, although she was free-born, she was a heathen and, moreover, had been drunk at the time."

Penn’s books are all exercises in "microhistory", focusing on an individual or an event to draw a picture of the cultural context. "Detail is important, it gives insight into what was happening around them. Landscape is important too. The stories are very much situated in the landscape of the Cape interior."

...

THE importance of landscape is beautifully illustrated in the story of Maria Mouton, married at the age of 16 to a free burgher, "Schurfde Frans" (Rough Frans), and the only woman in the 18th century to be executed at the Cape. Mouton was executed for inciting her slave lover to murder Frans in the horseshoe-shaped valley of the Land van Waveren (Tulbagh). Penn’s telling of the story shows how she might easily have got away with it for longer because of the farm’s isolation.

Penn first pored through the national archives when he was looking into "what happened to the Khoi in the 18th century" for his doctorate. It was a time he describes as "the vital years of their destiny".

"It was hard to master the VOC (Dutch East India Company) archive for the 18th century," he says. "I had very elementary Afrikaans and (the records) are in 18th century Dutch. It took about 10 years."

After gaining his doctorate in history, Penn continued his research, relying heavily on the criminal records, and some trips to archaeological sites, looking into Khoikhoi lifestyles.

Change: -0.47%

Change: -0.57%

Change: -1.76%

Change: -0.34%

Change: 0.02%

Data supplied by Profile Data

Change: -1.40%

Change: -0.42%

Change: -0.47%

Change: 0.00%

Change: -0.47%

Data supplied by Profile Data

Change: 1.29%

Change: 1.53%

Change: 1.22%

Change: 1.10%

Change: 1.05%

Data supplied by Profile Data

Change: 0.04%

Change: -0.52%

Change: 0.20%

Change: -1.38%

Change: -2.05%

Data supplied by Profile Data