THE world may be generally less violent than in any other time in history, but politically it is "bonkers", says British award-winning investigative journalist Misha Glenny. He has also advised the US and some European countries on policy.

Glenny arrived in South Africa for Christmas and to promote his latest book just as President Jacob Zuma fired Finance Minister Nhlanhla Nene, sending the rand and the bond market into a tailspin.

"I’m speechless," says Glenny, who has seen at least one political nadir — he spent years covering the Yugoslavian wars, fought from 1991 to 2001. "How anyone can be so politically crass?"

But it’s not just South Africa that has Glenny incredulous. There is the US presidential election build-up that has brought the country right-wing contenders such as Donald Trump, the myriad Middle Eastern problems, and Europe is facing a crisis on a scale not seen since the Second World War.

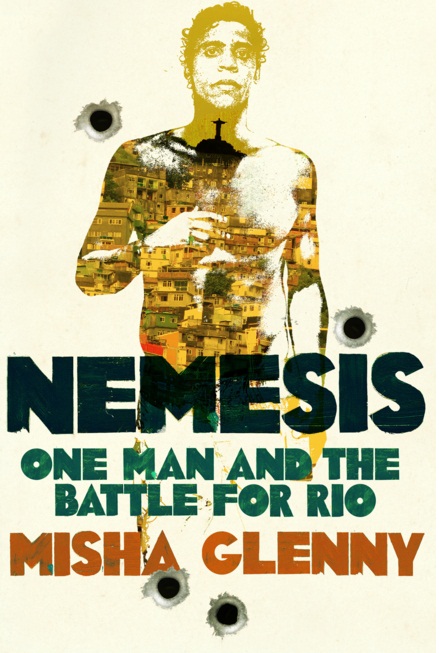

He sees several parallels between South Africa and the country his latest book explores. Nemesis: One Man and the Battle for Rio is the story of how one unremarkable youngster became a criminal kingpin, controlling the largest favela (slum) in Brazil’s Rio de Janeiro. It is also the story of Brazil after the 1985 collapse of military dictatorship.

This is a different tack from his other books, which take a macro view.

"The thing is, how do you get people engaged with complex subjects?" he says. "The best way is to look for interesting characters. I felt with the (other books) there wasn’t that engagement."

Just as the ruling African National Congress is slowly seeing its power crumble, so the Brazilian ruling Worker’s Party’s hegemony is "no longer internally assured". The countries also share an inability to overcome crippling social inequality, which Glenny says in Brazil’s case is holding it back from being the most powerful country in the world.

South Africa may be slightly ahead of Brazil in that it does not have to contend with the scale of drug consumption that goes with being a huge transit route for cocaine, but Brazil has never had institutionalised racism, even though it received 5-million slaves from Africa during the slave trade era. This, however, does not absolve it from race-based social problems.

...

GLENNY’s strategy has worked. Nemesis shows deftly how no one is able to escape the influence of the time and place into which they are born. Antônio Francisco Bonfim Lopes entered life in Rio de Janeiro’s most populous favela, Rocinha, in 1976. By the time he was arrested in November 2011 he was notorious throughout Rio, and — in some circles — the world. He was the city’s most wanted man.

It would be easy to dismiss Lopes’s arrest as simply the end of another bad guy’s rule, but Glenny’s meticulous research and critical yet compassionate writing mean this is a treatise on how life is never simple.

Glenny has made a career of excavating the darker regions of the modern world. His books include McMafia: Seriously Organised Crime; DarkMarket: How Hackers Became the New Mafia; and three books on the Balkan conflicts. This book adds to a formidable repertoire.

He shows how Lopes first stepped into criminal life when he made a Faustian pact with a Rocinha drugs don: money to save a beloved but sickly daughter in exchange for his service, but he does not leave the man off the hook.

"He could have stepped away (from a life of crime), but I think he came to love the power and adulation, the glamorous wife...."

...

LOPES stepped into a vortex powered by cocaine’s rise in popularity during the late ’80s and the ’90s, Brazil’s emergence from military dictatorship and its salvation from runaway inflation, all at a time of increasing urbanisation. Where a similarly talented but more privileged youngster might have used his innate talents to rise in the corporate world, Lopes used his to rise within the favela’s drugs gang, ultimately becoming don.

Growing up in Rocinha had shown Lopes that it was important to win community backing through handing out food parcels, and money for medicines, funerals and other expenses, even dispensing sweets to children. Under Lopes’s rule in Rocinha, murder, domestic violence and petty crime and even drug dealing were relatively rare, yet all was ruled by a drug lord.

Glenny shows how Lopes is part author of his own destiny, part flotsam on broader tides.

Tackling the rise and fall of a Rio de Janeiro druglord, Misha Glenny shows how life is never simple, and that it was not just a matter of the end of another bad guy’s rule. Picture : TED

THE world may be generally less violent than in any other time in history, but politically it is "bonkers", says British award-winning investigative journalist Misha Glenny. He has also advised the US and some European countries on policy.

Glenny arrived in South Africa for Christmas and to promote his latest book just as President Jacob Zuma fired Finance Minister Nhlanhla Nene, sending the rand and the bond market into a tailspin.

"I’m speechless," says Glenny, who has seen at least one political nadir — he spent years covering the Yugoslavian wars, fought from 1991 to 2001. "How anyone can be so politically crass?"

But it’s not just South Africa that has Glenny incredulous. There is the US presidential election build-up that has brought the country right-wing contenders such as Donald Trump, the myriad Middle Eastern problems, and Europe is facing a crisis on a scale not seen since the Second World War.

He sees several parallels between South Africa and the country his latest book explores. Nemesis: One Man and the Battle for Rio is the story of how one unremarkable youngster became a criminal kingpin, controlling the largest favela (slum) in Brazil’s Rio de Janeiro. It is also the story of Brazil after the 1985 collapse of military dictatorship.

This is a different tack from his other books, which take a macro view.

"The thing is, how do you get people engaged with complex subjects?" he says. "The best way is to look for interesting characters. I felt with the (other books) there wasn’t that engagement."

Just as the ruling African National Congress is slowly seeing its power crumble, so the Brazilian ruling Worker’s Party’s hegemony is "no longer internally assured". The countries also share an inability to overcome crippling social inequality, which Glenny says in Brazil’s case is holding it back from being the most powerful country in the world.

South Africa may be slightly ahead of Brazil in that it does not have to contend with the scale of drug consumption that goes with being a huge transit route for cocaine, but Brazil has never had institutionalised racism, even though it received 5-million slaves from Africa during the slave trade era. This, however, does not absolve it from race-based social problems.

...

GLENNY’s strategy has worked. Nemesis shows deftly how no one is able to escape the influence of the time and place into which they are born. Antônio Francisco Bonfim Lopes entered life in Rio de Janeiro’s most populous favela, Rocinha, in 1976. By the time he was arrested in November 2011 he was notorious throughout Rio, and — in some circles — the world. He was the city’s most wanted man.

It would be easy to dismiss Lopes’s arrest as simply the end of another bad guy’s rule, but Glenny’s meticulous research and critical yet compassionate writing mean this is a treatise on how life is never simple.

Glenny has made a career of excavating the darker regions of the modern world. His books include McMafia: Seriously Organised Crime; DarkMarket: How Hackers Became the New Mafia; and three books on the Balkan conflicts. This book adds to a formidable repertoire.

He shows how Lopes first stepped into criminal life when he made a Faustian pact with a Rocinha drugs don: money to save a beloved but sickly daughter in exchange for his service, but he does not leave the man off the hook.

"He could have stepped away (from a life of crime), but I think he came to love the power and adulation, the glamorous wife...."

...

LOPES stepped into a vortex powered by cocaine’s rise in popularity during the late ’80s and the ’90s, Brazil’s emergence from military dictatorship and its salvation from runaway inflation, all at a time of increasing urbanisation. Where a similarly talented but more privileged youngster might have used his innate talents to rise in the corporate world, Lopes used his to rise within the favela’s drugs gang, ultimately becoming don.

Growing up in Rocinha had shown Lopes that it was important to win community backing through handing out food parcels, and money for medicines, funerals and other expenses, even dispensing sweets to children. Under Lopes’s rule in Rocinha, murder, domestic violence and petty crime and even drug dealing were relatively rare, yet all was ruled by a drug lord.

Glenny shows how Lopes is part author of his own destiny, part flotsam on broader tides.

Change: -0.02%

Change: -0.05%

Change: -1.34%

Change: -0.02%

Change: 1.33%

Data supplied by Profile Data

Change: -0.20%

Change: -0.65%

Change: -0.02%

Change: 0.00%

Change: -0.50%

Data supplied by Profile Data

Change: 0.46%

Change: 0.39%

Change: 0.24%

Change: 2.19%

Change: -0.34%

Data supplied by Profile Data

Change: 1.58%

Change: 1.69%

Change: 1.59%

Change: -0.93%

Change: -1.08%

Data supplied by Profile Data