BOOK REVIEW: I Ran For My Life

by Lungile Sojini,

2015-12-11 05:30:00.0

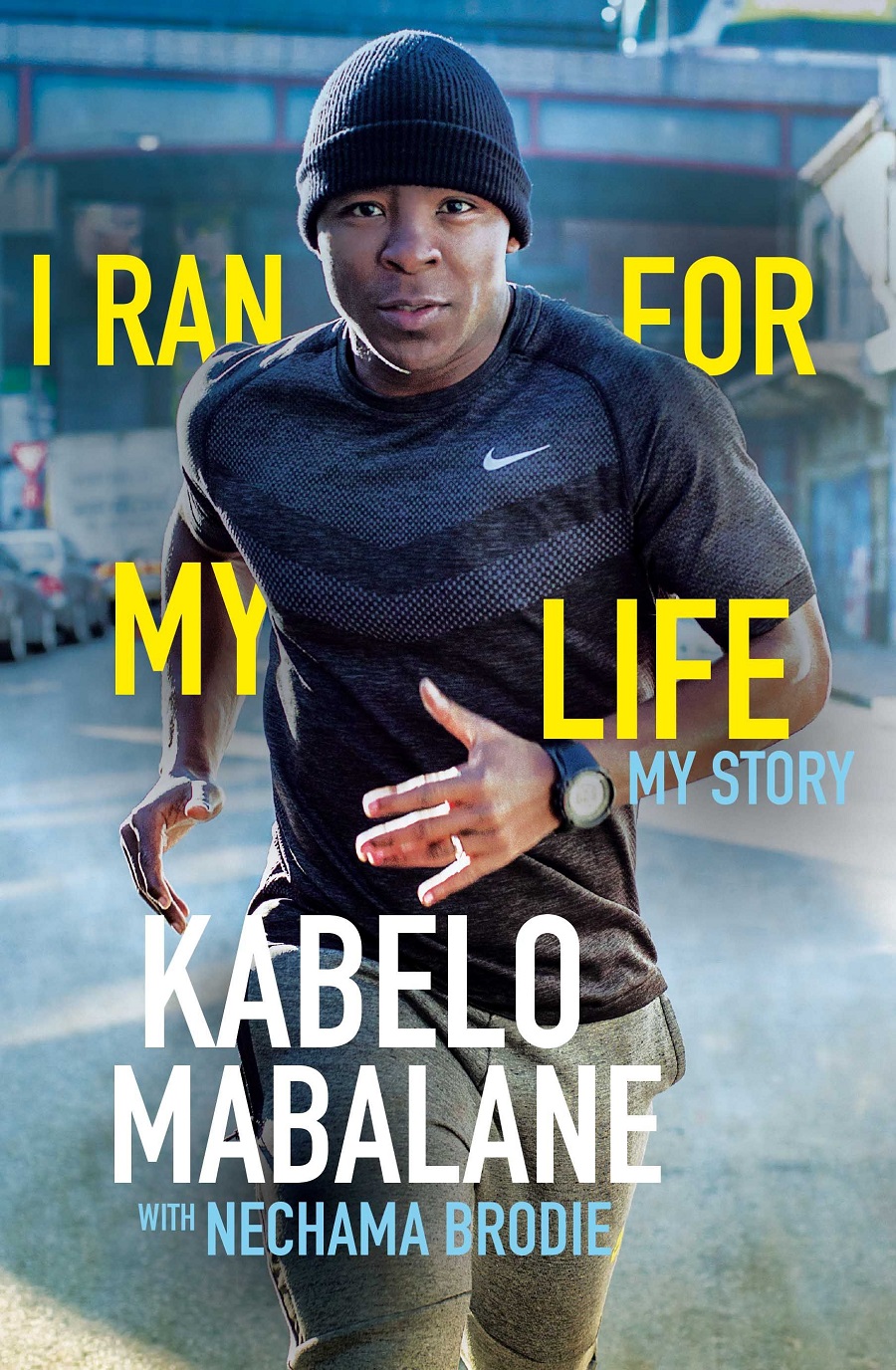

RUNNING for your life takes on new meaning in a book by musician and TV personality Kabelo Mabalane. I Ran For My Life, his 216-page biography, is a collaboration between Mabalane and journalist and author Nechama Brodie.

Brodie has previously written The Cape Town Book and The Joburg Book.

I Ran For My Life is her first biography.

Mabalane and Brodie share the same passions — music and running — but that is where the similarities between them end, and where Mabalane’s conflicted past starts.

The recollections start in 1976, the year of the student uprisings, in Mabalane’s home in Pimville, Soweto. What follows is the journey of a young, innocent kid whose mother instilled in him a fighting spirit.

Pimville is also where Mabalane first fell in love with music. He describes the lessons he learned from his alcoholic father and the tension between them — perhaps a father who never understood his son’s career choice.

Mabalane sketches what it was like learning at the prestigious, predominantly white, Johannesburg private school St Stithians. The school was also the place in which he met Tokollo Tshabalala, with whom he formed TKZee, a kwaito band that made them, and third band member, Zwai Bala, household names.

Just as Mabalane rightly notes in the book that you can’t talk about kwaito without talking about TKZee, you can’t write about Mabalane without talking about Tshabalala and Bala.

This the book seeks to justify as it recounts the stories of their wayward behaviour just as their fame blossomed: stories of getting drunk and taking ecstasy, assault, bribing cops and sleeping in futon beds in fancy Johannesburg suburbs. Of whiskey and cocaine. (As for Tshabalala, he is still unrepentant, and often in the news for the wrong reasons.)

THEY made good music, reckons Mabalane. The drugs, however, set them up for failure, their fallouts scrutinised and documented in the media.

The book also touches on what their individual roles as group members were. These differences (their personalities, skills sets and mentalities), became the seeds of destruction in later years.

Mabalane’s insecurities are laid bare in the book. It was these insecurities, he recounts, that led him to drugs and booze.

Drugs aside, this is also a book about redemption and salvation, perhaps where the phrase "I ran for my life" comes into play.

Mabalane portrays jogging as his saving grace. It was a starting point in his regeneration tale. We see him also as father and husband — his TKZee days long over, his drugs and alcohol days long forgotten, running and religion replacing his former vices.

He carefully scrutinises his choices; even his musical choices are questioned. And his dilemma (now that his intentions to lead a cleaner and more meaningful life): to become a gospel singer or just make kwaito music that has a positive message, despite it being associated with the life he wanted to leave behind.

The book ends with a large batch of articles on running, some by Brodie herself, others by newspaper columnist and sports nutritionist Dr Ross Tucker and official Comrades Marathon coach and biokineticist Lindsey Parry.

Mabalane also lists more than 10 songs he listens when he’s running.

While the book might not excite someone who isn’t into running, Mabalane’s biography is amazing on its own.

Picture: THINKSTOCK

RUNNING for your life takes on new meaning in a book by musician and TV personality Kabelo Mabalane. I Ran For My Life, his 216-page biography, is a collaboration between Mabalane and journalist and author Nechama Brodie.

Brodie has previously written The Cape Town Book and The Joburg Book.

I Ran For My Life is her first biography.

Mabalane and Brodie share the same passions — music and running — but that is where the similarities between them end, and where Mabalane’s conflicted past starts.

The recollections start in 1976, the year of the student uprisings, in Mabalane’s home in Pimville, Soweto. What follows is the journey of a young, innocent kid whose mother instilled in him a fighting spirit.

Pimville is also where Mabalane first fell in love with music. He describes the lessons he learned from his alcoholic father and the tension between them — perhaps a father who never understood his son’s career choice.

Mabalane sketches what it was like learning at the prestigious, predominantly white, Johannesburg private school St Stithians. The school was also the place in which he met Tokollo Tshabalala, with whom he formed TKZee, a kwaito band that made them, and third band member, Zwai Bala, household names.

Just as Mabalane rightly notes in the book that you can’t talk about kwaito without talking about TKZee, you can’t write about Mabalane without talking about Tshabalala and Bala.

This the book seeks to justify as it recounts the stories of their wayward behaviour just as their fame blossomed: stories of getting drunk and taking ecstasy, assault, bribing cops and sleeping in futon beds in fancy Johannesburg suburbs. Of whiskey and cocaine. (As for Tshabalala, he is still unrepentant, and often in the news for the wrong reasons.)

THEY made good music, reckons Mabalane. The drugs, however, set them up for failure, their fallouts scrutinised and documented in the media.

The book also touches on what their individual roles as group members were. These differences (their personalities, skills sets and mentalities), became the seeds of destruction in later years.

Mabalane’s insecurities are laid bare in the book. It was these insecurities, he recounts, that led him to drugs and booze.

Drugs aside, this is also a book about redemption and salvation, perhaps where the phrase "I ran for my life" comes into play.

Mabalane portrays jogging as his saving grace. It was a starting point in his regeneration tale. We see him also as father and husband — his TKZee days long over, his drugs and alcohol days long forgotten, running and religion replacing his former vices.

He carefully scrutinises his choices; even his musical choices are questioned. And his dilemma (now that his intentions to lead a cleaner and more meaningful life): to become a gospel singer or just make kwaito music that has a positive message, despite it being associated with the life he wanted to leave behind.

The book ends with a large batch of articles on running, some by Brodie herself, others by newspaper columnist and sports nutritionist Dr Ross Tucker and official Comrades Marathon coach and biokineticist Lindsey Parry.

Mabalane also lists more than 10 songs he listens when he’s running.

While the book might not excite someone who isn’t into running, Mabalane’s biography is amazing on its own.

Change: 2.48%

Change: 2.53%

Change: 2.08%

Change: 1.97%

Change: 5.33%

Data supplied by Profile Data

Change: 0.00%

Change: 0.00%

Change: 2.48%

Change: 0.00%

Change: 0.00%

Data supplied by Profile Data

Change: 0.44%

Change: 0.11%

Change: -0.76%

Change: -0.92%

Change: -0.23%

Data supplied by Profile Data

Change: 0.00%

Change: 0.00%

Change: 0.00%

Change: 0.00%

Change: 0.00%

Data supplied by Profile Data