Do we want a system that allows a judge to separate justice and the law?

by Steven Friedman,

2016-03-16 05:45:46.0

WHEN a judge tells the widow of a man whose murderer killed him in the hope of starting a civil war that she should "move on" and then orders the release of the killer, who has served less time than Nelson Mandela, people are entitled to ask whether the legal system cares about justice.

A Pretoria judge’s decision to overrule the justice minister and order the release of Janusz Walus, killer of South African Communist Party and African National Congress leader Chris Hani — while delivering the most insensitive judicial comment in years — has outraged a wide political spectrum. It has also questioned three firmly-held beliefs: That the courts are always good, the government is always bad and that the official approach to reconciliation here works.

Anger over the ruling is understandable. Killing someone because you dislike their politics is always horrifying. But Walus and his co-conspirator, Clive Derby-Lewis, also testified at their trial that they did it because they wanted to start a bloodbath that would prevent democracy.

This is why the ruling raises uncomfortable questions about the connection between law and justice here. When Barend Strydom, who gunned down people in a street simply because they were black, was granted amnesty by the apartheid government, one commentator asked how it could ever be moral not to pardon any criminal ever again. What deed could be worse than killing others simply because of their race?

Walus’s parole raises a similar question. If people who murder in the hope of starting a racial war don’t have to serve their full sentence, who does? What deed is worse than his? Inevitably, the judgment is compared with the continued imprisonment of soldiers of the Pan Africanist Congress’s Apla army: why were their deeds worse than Walus’s? Is fighting a guerrilla war to end racial rule worse than killing someone in their driveway because you want racism to continue?

The ruling is a set-back for the justice system first because the ruling was, to many black people, a stark example of how black pain is often treated. Racial progress here is often blocked when blacks are repeatedly told to "move on" when they complain that they are still not treated as equals. But it was also a blow because the wedge between justice and what the judge was allowed to do is so wide that some question whether we want the rule of law if it allows judges to do this. A cornerstone of our democracy, a credible judiciary, is under threat and will remain so unless this anger is heard.

One way to do this is to rely on the system by appealing against the judgment and hoping that higher courts will take justice more seriously. This is the path urged by lawyers who argue that judgments like this can be set to rights by the law’s appeal procedures. But, if that does not work, the country may need an overdue debate on whether we can always trust the judiciary, rather than politics, to ensure that justice is done.

This time, the minister’s political decision to deny parole comes far closer to a sense of justice than the judge’s judicial ruling. And that suggests that, if democratic rules are followed, giving more power to politicians rather than judges may sometimes make justice more likely.

One possibility is a law that tells judges what to take into account when they decide on parole appeals. Another would be a public more active in pressing the Judicial Services Commission to ensure that no-one is appointed to the bench unless their sense of justice is consistent with democratic values.

Many in the mainstream would denounce both as "political" interference with the courts. But we now see that the biases of judges can be as much a problem as those of politicians.

The judgment has also focused attention on the type of reconciliation the elites have favoured since 1994. By allowing anyone who committed abuses amnesty if they told the whole story and there was a clear connection between what they did and their political goal, this approach allowed amnesty for hideous crimes for people who did not even have to say sorry — and certainly did not have to do anything to show remorse.

Besides insulting the memory of the victims and showing as much sensitivity to their families as the judge who freed Walus did, this may have done much to encourage a sense of impunity: if multiple killers can go home without even saying sorry, why should anyone else pay for their crimes?

But its main flaw is that it separated the deeds from their context: in this view, what people did mattered, not why they did it. It is this tunnel vision that cannot see Walus as a man who tried to start a war.

That said, the decision to release Walus could be a blessing in disguise. Precisely because it raises such uncomfortable questions on judges’ roles and the official brand of reconciliation, it may trigger a search for more democratic and humane approaches. If it does, it will accidentally have made a free and just society more likely.

• Friedman is director of the Centre for the Study of Democracy

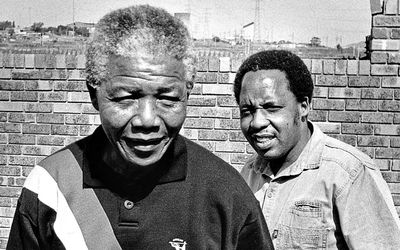

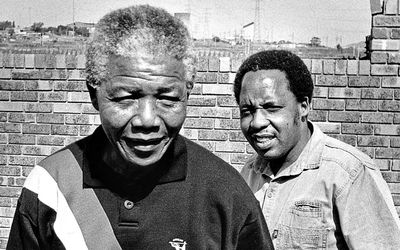

Former president Nelson Mandela and Chris Hani

WHEN a judge tells the widow of a man whose murderer killed him in the hope of starting a civil war that she should "move on" and then orders the release of the killer, who has served less time than Nelson Mandela, people are entitled to ask whether the legal system cares about justice.

A Pretoria judge’s decision to overrule the justice minister and order the release of Janusz Walus, killer of South African Communist Party and African National Congress leader Chris Hani — while delivering the most insensitive judicial comment in years — has outraged a wide political spectrum. It has also questioned three firmly-held beliefs: That the courts are always good, the government is always bad and that the official approach to reconciliation here works.

Anger over the ruling is understandable. Killing someone because you dislike their politics is always horrifying. But Walus and his co-conspirator, Clive Derby-Lewis, also testified at their trial that they did it because they wanted to start a bloodbath that would prevent democracy.

This is why the ruling raises uncomfortable questions about the connection between law and justice here. When Barend Strydom, who gunned down people in a street simply because they were black, was granted amnesty by the apartheid government, one commentator asked how it could ever be moral not to pardon any criminal ever again. What deed could be worse than killing others simply because of their race?

Walus’s parole raises a similar question. If people who murder in the hope of starting a racial war don’t have to serve their full sentence, who does? What deed is worse than his? Inevitably, the judgment is compared with the continued imprisonment of soldiers of the Pan Africanist Congress’s Apla army: why were their deeds worse than Walus’s? Is fighting a guerrilla war to end racial rule worse than killing someone in their driveway because you want racism to continue?

The ruling is a set-back for the justice system first because the ruling was, to many black people, a stark example of how black pain is often treated. Racial progress here is often blocked when blacks are repeatedly told to "move on" when they complain that they are still not treated as equals. But it was also a blow because the wedge between justice and what the judge was allowed to do is so wide that some question whether we want the rule of law if it allows judges to do this. A cornerstone of our democracy, a credible judiciary, is under threat and will remain so unless this anger is heard.

One way to do this is to rely on the system by appealing against the judgment and hoping that higher courts will take justice more seriously. This is the path urged by lawyers who argue that judgments like this can be set to rights by the law’s appeal procedures. But, if that does not work, the country may need an overdue debate on whether we can always trust the judiciary, rather than politics, to ensure that justice is done.

This time, the minister’s political decision to deny parole comes far closer to a sense of justice than the judge’s judicial ruling. And that suggests that, if democratic rules are followed, giving more power to politicians rather than judges may sometimes make justice more likely.

One possibility is a law that tells judges what to take into account when they decide on parole appeals. Another would be a public more active in pressing the Judicial Services Commission to ensure that no-one is appointed to the bench unless their sense of justice is consistent with democratic values.

Many in the mainstream would denounce both as "political" interference with the courts. But we now see that the biases of judges can be as much a problem as those of politicians.

The judgment has also focused attention on the type of reconciliation the elites have favoured since 1994. By allowing anyone who committed abuses amnesty if they told the whole story and there was a clear connection between what they did and their political goal, this approach allowed amnesty for hideous crimes for people who did not even have to say sorry — and certainly did not have to do anything to show remorse.

Besides insulting the memory of the victims and showing as much sensitivity to their families as the judge who freed Walus did, this may have done much to encourage a sense of impunity: if multiple killers can go home without even saying sorry, why should anyone else pay for their crimes?

But its main flaw is that it separated the deeds from their context: in this view, what people did mattered, not why they did it. It is this tunnel vision that cannot see Walus as a man who tried to start a war.

That said, the decision to release Walus could be a blessing in disguise. Precisely because it raises such uncomfortable questions on judges’ roles and the official brand of reconciliation, it may trigger a search for more democratic and humane approaches. If it does, it will accidentally have made a free and just society more likely.

• Friedman is director of the Centre for the Study of Democracy

Change: 1.19%

Change: 1.36%

Change: 2.19%

Change: 1.49%

Change: -0.77%

Data supplied by Profile Data

Change: -0.19%

Change: 0.69%

Change: 1.19%

Change: 0.00%

Change: 0.44%

Data supplied by Profile Data

Change: 0.62%

Change: 0.61%

Change: 0.23%

Change: 0.52%

Change: 0.12%

Data supplied by Profile Data

Change: -0.21%

Change: -1.22%

Change: -0.69%

Change: -0.51%

Change: 0.07%

Data supplied by Profile Data