Hacked 3D printer key to making organs

by John Tozzi,

2015-11-19 06:02:08.0

WHEN Adam Feinberg tried to figure out how to synthesise human tissue four years ago, his supplies were prosaic: a kitchen blender, some gelatin packets from the supermarket baking aisle, and a 3D printer that cost $2,000.

"I had no external funding when I started, so we did it kind of on the cheap," says Feinberg, 38, a biomedical engineer who runs a laboratory at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh, US.

In a paper published in Science Advances, he and his colleagues describe how they refined the technique to print structural replicas of the tissue of arteries, brains, and other organs out of proteins such as collagen and fibrin.

While the forms they created aren’t functioning organs with living cells, they could one day act as a scaffold on which to grow actual tissues. Doctors have already used 3D printing to support an infant’s damaged windpipe, create a titanium jaw replacement, and synthesise tiny livers to test potential drug therapies.

Building functioning, custom organs ready for implant is still many hurdles away. But the new research brings the futuristic promise of bespoke tissues for medical therapies closer to reality.

Feinberg’s fundamental advance is figuring out how to keep the soft structures created by a modified MakerBot 3D printer from collapsing under their own weight. Unlike plastic — the normal material of a 3D printer — collagen won’t hold its shape as it is being synthesised unless it has some support.

The research team started thinking about how jelly moulds can suspend pieces of fruit in a sugary gel. They experimented with gelatin, blending it into a slurry of fine particles. The slurry would support the structure being built, layer by layer, while still allowing the printer’s nozzle — modified with a syringe — to move freely. When the printed object was complete, it would hold together on its own, and the supporting gel could be melted away in water at body temperature.

The relative simplicity of the process means it will allow others to build on the innovation, says Tommy Angelini, a University of Florida professor whose laboratory recently published a similar method for engineering complex tissues. He wasn’t involved in Feinberg’s research.

"It’s a very accessible, versatile method," he says.

Cooking up tissues that can be implanted into patients remains a challenge for the future. "That’s going to happen eventually, but there’s still so much fundamental science to be done," Angelini says.

In the near future, the new method of 3D printing might let doctors test medical treatments on laboratory replicas of patients’ own body parts. Drug companies could use such models to test risky new drugs before they’re used in humans.

"Right now, we have animal models — mice and rats — and we have (human) clinical trials, and not a lot inbetween," Feinberg says. "You can potentially make ... a patient-specific piece of heart muscle."

Feinberg’s research was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health and the National Science Foundation. But the shoestring strategy he started with — hacking an off-the-shelf printer and buying some gelatin packs — still informs how his laboratory works.

Although Carnegie Mellon has applied for a patent on the support bath, his team is releasing information on how to modify the MakerBot printer to handle biological materials under open-source licences. He has also demonstrated the bioprinting technique at a local school, using chocolate frosting instead of collagen.

"We think it’s a lot easier to use these less expensive machines," Feinberg says. "We can essentially modify it any way we need to make it work."

Bloomberg

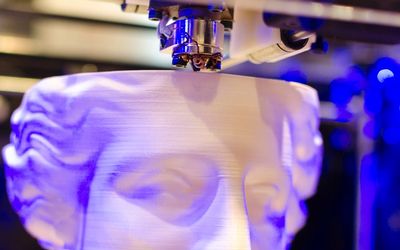

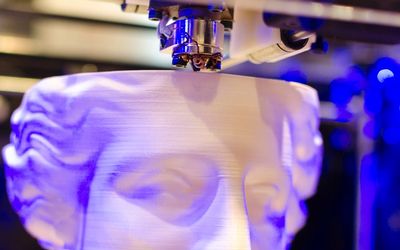

A new 3D printing method might let doctors test treatments on body part replicas. Picture: ISTOCK

WHEN Adam Feinberg tried to figure out how to synthesise human tissue four years ago, his supplies were prosaic: a kitchen blender, some gelatin packets from the supermarket baking aisle, and a 3D printer that cost $2,000.

"I had no external funding when I started, so we did it kind of on the cheap," says Feinberg, 38, a biomedical engineer who runs a laboratory at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh, US.

In a paper published in Science Advances, he and his colleagues describe how they refined the technique to print structural replicas of the tissue of arteries, brains, and other organs out of proteins such as collagen and fibrin.

While the forms they created aren’t functioning organs with living cells, they could one day act as a scaffold on which to grow actual tissues. Doctors have already used 3D printing to support an infant’s damaged windpipe, create a titanium jaw replacement, and synthesise tiny livers to test potential drug therapies.

Building functioning, custom organs ready for implant is still many hurdles away. But the new research brings the futuristic promise of bespoke tissues for medical therapies closer to reality.

Feinberg’s fundamental advance is figuring out how to keep the soft structures created by a modified MakerBot 3D printer from collapsing under their own weight. Unlike plastic — the normal material of a 3D printer — collagen won’t hold its shape as it is being synthesised unless it has some support.

The research team started thinking about how jelly moulds can suspend pieces of fruit in a sugary gel. They experimented with gelatin, blending it into a slurry of fine particles. The slurry would support the structure being built, layer by layer, while still allowing the printer’s nozzle — modified with a syringe — to move freely. When the printed object was complete, it would hold together on its own, and the supporting gel could be melted away in water at body temperature.

The relative simplicity of the process means it will allow others to build on the innovation, says Tommy Angelini, a University of Florida professor whose laboratory recently published a similar method for engineering complex tissues. He wasn’t involved in Feinberg’s research.

"It’s a very accessible, versatile method," he says.

Cooking up tissues that can be implanted into patients remains a challenge for the future. "That’s going to happen eventually, but there’s still so much fundamental science to be done," Angelini says.

In the near future, the new method of 3D printing might let doctors test medical treatments on laboratory replicas of patients’ own body parts. Drug companies could use such models to test risky new drugs before they’re used in humans.

"Right now, we have animal models — mice and rats — and we have (human) clinical trials, and not a lot inbetween," Feinberg says. "You can potentially make ... a patient-specific piece of heart muscle."

Feinberg’s research was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health and the National Science Foundation. But the shoestring strategy he started with — hacking an off-the-shelf printer and buying some gelatin packs — still informs how his laboratory works.

Although Carnegie Mellon has applied for a patent on the support bath, his team is releasing information on how to modify the MakerBot printer to handle biological materials under open-source licences. He has also demonstrated the bioprinting technique at a local school, using chocolate frosting instead of collagen.

"We think it’s a lot easier to use these less expensive machines," Feinberg says. "We can essentially modify it any way we need to make it work."

Bloomberg

Change: -0.47%

Change: -0.57%

Change: -1.76%

Change: -0.34%

Change: 0.02%

Data supplied by Profile Data

Change: -1.40%

Change: -0.42%

Change: -0.47%

Change: 0.00%

Change: -0.47%

Data supplied by Profile Data

Change: 1.29%

Change: 1.53%

Change: 1.22%

Change: 1.10%

Change: 1.05%

Data supplied by Profile Data

Change: 0.04%

Change: -0.52%

Change: 0.20%

Change: -1.38%

Change: -2.05%

Data supplied by Profile Data