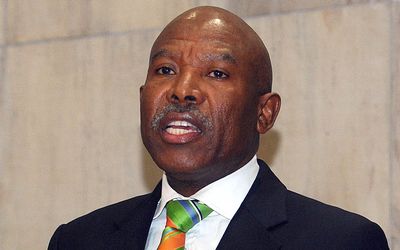

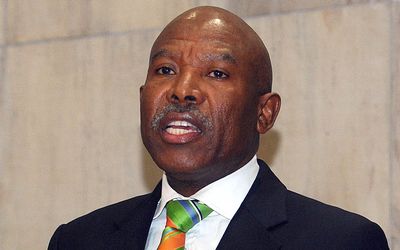

EXPLAINING the monetary policy committee’s decision to raise interest rates last week, Reserve Bank governor Lesetja Kganyago flagged the rand exchange rate as the main risk to the Bank’s inflation forecast, which already sees inflation breaching the top of the 3%-6% target range for the first half of next year.

He talked particularly of the risks to the rand when the US Federal Reserve starts to hike rates as expected — just as capital inflows surged when US interest rates were zero and quantitative easing was in place, so those inflows could reverse when US monetary policy normalises. That meant South African assets would have to reprice, said Kganyago. The rand is the most likely candidate to bear the brunt of that repricing.

The committee’s concern is about the "second round" effects on inflation that could result.

The rand might have been expected to stabilise, or gain, in response to the committee’s firm action. But not a day later it plunged to its lowest level since the December 2001 rand crash. It wasn’t the Fed this time — it was the rout in commodity prices, prompted by more bad news out of China. Commodity currencies and those of emerging markets have been hit across the board by plummeting prices, but the rand has been one of the worst hit.

At a time when the world is a very volatile and uncertain place, global investors tend to become more picky about where they put their money — and SA, as Kganyago said, is particularly vulnerable compared to other emerging markets because of its twin fiscal and balance of payment current account deficits — which have to be financed by uncertain and volatile inflows of foreign cash.

Just how vulnerable is clear from recent research by Standard Bank’s economists, who have found that the rand is more sensitive to the current account deficit than at any time since 2001. The difference: then we had a slight surplus; now we have a deficit wider than most of our emerging market peers. So is our fiscal deficit.

When the world was awash with liquidity after the global financial crisis, no one cared much about the current account deficit. Now they do, and Standard Bank head of SA research Walter de Wet estimates the combination of the high sensitivity and the high current account deficit has had a negative effect of R2.50 on the rand-dollar exchange rate over the past five years. It’s not surprising then that the committee wanted to take pre-emptive action to curb possible inflationary pressures if the rand’s slide feeds through to higher inflation expectations and spiralling prices. Rather than "front-running" the Fed, the committee may even have wanted to send a clear signal that it was serious about inflation now — just in case the Fed waits a bit longer to hike, perhaps making it harder to justify a rate hike in SA, which is already one of only a few countries where the policy interest rate is going up, even if gently.

One can’t help wondering whether the Reserve Bank feels it needs to work particularly hard to ensure it is seen as credible and consistent, in an environment where other economic policy makers are sending such inconsistent signals to investors.

The question is what happens now. One issue is what happens to the current account deficit. The oil price is falling, along with other commodity prices, and SA benefits from that. But oil is only a fifth of our imports while commodities such as iron ore, platinum and coal are more than half of our exports, so the effect on our terms of trade is still negative — which is bad for the current account.

Against that, though, the weaker rand should be good for the deficit and some economists reckon it is already helping to reduce it and would have helped more if commodity prices had been more stable.

The other question is how much the exchange rate affects inflation. The "pass through" (of a weaker rand to higher inflation), has halved since the boom years in 2007, from about 37% to 17.7%, Standard Bank’s researchers estimate. That suggests there might be less reason to worry about an inflationary spiral, but no one is too sure what drives the pass-through rate, which could change.

What is certain is that while we can run a current account deficit, and SA will do so as long as we save less than we invest, and produce less than we consume, we will, increasingly, have to pay the price of doing so.

• Joffe is editor at large

South African Reserve Bank governor Lesetja Kganyago. Picture: PUXLEY MAKGATHO

EXPLAINING the monetary policy committee’s decision to raise interest rates last week, Reserve Bank governor Lesetja Kganyago flagged the rand exchange rate as the main risk to the Bank’s inflation forecast, which already sees inflation breaching the top of the 3%-6% target range for the first half of next year.

He talked particularly of the risks to the rand when the US Federal Reserve starts to hike rates as expected — just as capital inflows surged when US interest rates were zero and quantitative easing was in place, so those inflows could reverse when US monetary policy normalises. That meant South African assets would have to reprice, said Kganyago. The rand is the most likely candidate to bear the brunt of that repricing.

The committee’s concern is about the "second round" effects on inflation that could result.

The rand might have been expected to stabilise, or gain, in response to the committee’s firm action. But not a day later it plunged to its lowest level since the December 2001 rand crash. It wasn’t the Fed this time — it was the rout in commodity prices, prompted by more bad news out of China. Commodity currencies and those of emerging markets have been hit across the board by plummeting prices, but the rand has been one of the worst hit.

At a time when the world is a very volatile and uncertain place, global investors tend to become more picky about where they put their money — and SA, as Kganyago said, is particularly vulnerable compared to other emerging markets because of its twin fiscal and balance of payment current account deficits — which have to be financed by uncertain and volatile inflows of foreign cash.

Just how vulnerable is clear from recent research by Standard Bank’s economists, who have found that the rand is more sensitive to the current account deficit than at any time since 2001. The difference: then we had a slight surplus; now we have a deficit wider than most of our emerging market peers. So is our fiscal deficit.

When the world was awash with liquidity after the global financial crisis, no one cared much about the current account deficit. Now they do, and Standard Bank head of SA research Walter de Wet estimates the combination of the high sensitivity and the high current account deficit has had a negative effect of R2.50 on the rand-dollar exchange rate over the past five years. It’s not surprising then that the committee wanted to take pre-emptive action to curb possible inflationary pressures if the rand’s slide feeds through to higher inflation expectations and spiralling prices. Rather than "front-running" the Fed, the committee may even have wanted to send a clear signal that it was serious about inflation now — just in case the Fed waits a bit longer to hike, perhaps making it harder to justify a rate hike in SA, which is already one of only a few countries where the policy interest rate is going up, even if gently.

One can’t help wondering whether the Reserve Bank feels it needs to work particularly hard to ensure it is seen as credible and consistent, in an environment where other economic policy makers are sending such inconsistent signals to investors.

The question is what happens now. One issue is what happens to the current account deficit. The oil price is falling, along with other commodity prices, and SA benefits from that. But oil is only a fifth of our imports while commodities such as iron ore, platinum and coal are more than half of our exports, so the effect on our terms of trade is still negative — which is bad for the current account.

Against that, though, the weaker rand should be good for the deficit and some economists reckon it is already helping to reduce it and would have helped more if commodity prices had been more stable.

The other question is how much the exchange rate affects inflation. The "pass through" (of a weaker rand to higher inflation), has halved since the boom years in 2007, from about 37% to 17.7%, Standard Bank’s researchers estimate. That suggests there might be less reason to worry about an inflationary spiral, but no one is too sure what drives the pass-through rate, which could change.

What is certain is that while we can run a current account deficit, and SA will do so as long as we save less than we invest, and produce less than we consume, we will, increasingly, have to pay the price of doing so.

• Joffe is editor at large

Post a comment