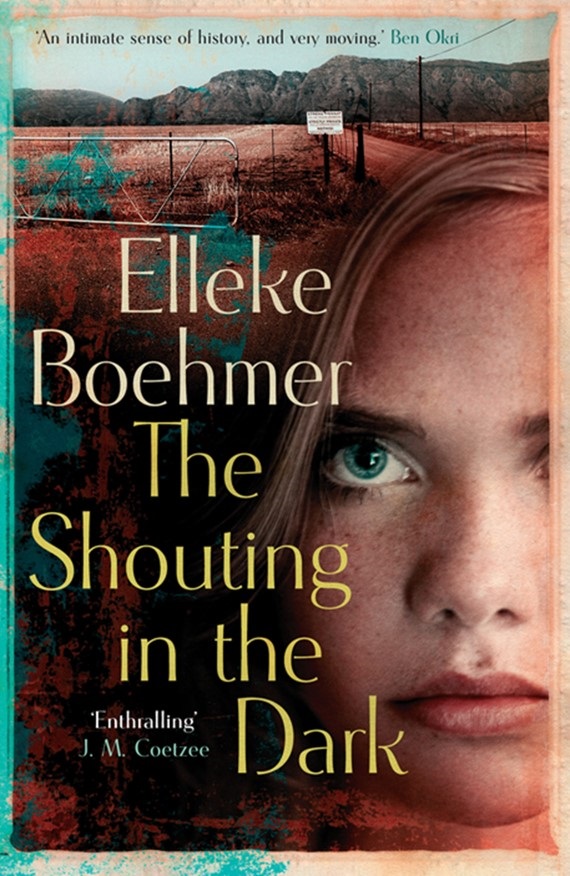

BOOK REVIEW: The Shouting in the Dark

by Sue Grant-Marshall,

2015-10-16 06:25:45.0

ELLEKE Boehmer, professor of World Literature in English at Oxford University, seems as far removed from flowing black graduation gowns and mortarboards as her astounding novel about a deeply dysfunctional South African family is from a donnish tome.

The Shouting in the Dark is her most autobiographical novel yet, though she’s quick to remind us that all writing is autobiographical, "think of JM Coetzee and Charles Dickens".

Boehmer (pronounced Burma) sets the story in 1970s Durban. A Dutch couple is raising their daughter, Ella. It is immediately clear she is regarded as a nuisance by both "the mother" and "the father", terms Boehmer uses to emphasise the stark lack of intimacy.

Ella, who wears a built-up shoe and is clearly clever, is sent to a remedial school. It becomes her refuge from the emotional battleground that is her home life.

Her neurotic, miserable mother feeds her tranquillisers to make her sleep and even straps her daughter to her bed. Ella’s rude, bullying father, who spews invective daily at both the insomniac mother and the terrified Ella — she hides a great deal in the garden — is suffering from post-traumatic stress brought on by his experiences in the Dutch navy in the Second World War. But this disorder was not a recognised condition back then.

Ella, late at night, presses her face up against the bedroom window as she listens to her aging father ranting at the black African sky. She is trying to hear the stories he will not tell her, "probably because she’s not a son", says Boehmer.

Ella wants to understand what so enrages him that it leads to the shouting, which is liberally greased by alcohol.

Ella is also intensely curious about the identity of a beautiful woman in a portrait hanging in the house. This, it emerges, is her dead aunt Ella, her father’s first wife and sister of her mother. The latter, it is clear, is no more than a caretaker wife and Ella the unwanted product of an early union.

As she grows up she gains confidence, mostly because she is extremely well read, and erudite. She fights her abusive father with words when he belittles her, striking back at him by eschewing their home language for the English he so admires.

The author captures, with subtle and haunting descriptive prose, the blossoming young woman and her infatuation with the teenage gardener, Phineas. Boehmer was born and raised in Durban by Dutch parents. She wanted to confront the question of what a young person does, what resources are at their disposal and how they reinforce them, when they are confronted by the kind of domestic emotional abuse Ella experiences.

Resilience is at the heart of Boehmer’s work. She is recognised internationally for her research in postcolonial writing, theory and "the literature of empire". She focuses on issues of migration, identity and resistance, particularly in Africa and India, and has written and co-edited books and essays on the literature of these nations.

"I am fascinated by what resources it takes to resist oppression, whether by Ella or in situations of colonisation and apartheid. And part of that resistance is through words."

Boehmer has for 25 years now been producing what she calls, "materials in fiction and non-fiction" and says "the question of resilience continues to return".

Today, apart from her busy professorial life, she travels the world, as a distinguished visiting fellow at universities ranging from our own University of the Witwatersrand to others in Australia, Canada, Denmark, Sweden and Germany.

She has written about postcolonial authors, including Coetzee, Peter Carey, Tsitsi Dangarembga and Amitav Ghosh, and penned a short biography of Nelson Mandela in 2008.

Picture: THINKSTOCK

ELLEKE Boehmer, professor of World Literature in English at Oxford University, seems as far removed from flowing black graduation gowns and mortarboards as her astounding novel about a deeply dysfunctional South African family is from a donnish tome.

The Shouting in the Dark is her most autobiographical novel yet, though she’s quick to remind us that all writing is autobiographical, "think of JM Coetzee and Charles Dickens".

Boehmer (pronounced Burma) sets the story in 1970s Durban. A Dutch couple is raising their daughter, Ella. It is immediately clear she is regarded as a nuisance by both "the mother" and "the father", terms Boehmer uses to emphasise the stark lack of intimacy.

Ella, who wears a built-up shoe and is clearly clever, is sent to a remedial school. It becomes her refuge from the emotional battleground that is her home life.

Her neurotic, miserable mother feeds her tranquillisers to make her sleep and even straps her daughter to her bed. Ella’s rude, bullying father, who spews invective daily at both the insomniac mother and the terrified Ella — she hides a great deal in the garden — is suffering from post-traumatic stress brought on by his experiences in the Dutch navy in the Second World War. But this disorder was not a recognised condition back then.

Ella, late at night, presses her face up against the bedroom window as she listens to her aging father ranting at the black African sky. She is trying to hear the stories he will not tell her, "probably because she’s not a son", says Boehmer.

Ella wants to understand what so enrages him that it leads to the shouting, which is liberally greased by alcohol.

Ella is also intensely curious about the identity of a beautiful woman in a portrait hanging in the house. This, it emerges, is her dead aunt Ella, her father’s first wife and sister of her mother. The latter, it is clear, is no more than a caretaker wife and Ella the unwanted product of an early union.

As she grows up she gains confidence, mostly because she is extremely well read, and erudite. She fights her abusive father with words when he belittles her, striking back at him by eschewing their home language for the English he so admires.

The author captures, with subtle and haunting descriptive prose, the blossoming young woman and her infatuation with the teenage gardener, Phineas. Boehmer was born and raised in Durban by Dutch parents. She wanted to confront the question of what a young person does, what resources are at their disposal and how they reinforce them, when they are confronted by the kind of domestic emotional abuse Ella experiences.

Resilience is at the heart of Boehmer’s work. She is recognised internationally for her research in postcolonial writing, theory and "the literature of empire". She focuses on issues of migration, identity and resistance, particularly in Africa and India, and has written and co-edited books and essays on the literature of these nations.

"I am fascinated by what resources it takes to resist oppression, whether by Ella or in situations of colonisation and apartheid. And part of that resistance is through words."

Boehmer has for 25 years now been producing what she calls, "materials in fiction and non-fiction" and says "the question of resilience continues to return".

Today, apart from her busy professorial life, she travels the world, as a distinguished visiting fellow at universities ranging from our own University of the Witwatersrand to others in Australia, Canada, Denmark, Sweden and Germany.

She has written about postcolonial authors, including Coetzee, Peter Carey, Tsitsi Dangarembga and Amitav Ghosh, and penned a short biography of Nelson Mandela in 2008.

Change: 0.25%

Change: 0.36%

Change: 0.88%

Change: 0.11%

Change: 0.16%

Data supplied by Profile Data

Change: 0.00%

Change: 0.00%

Change: 0.25%

Change: 0.00%

Change: 0.00%

Data supplied by Profile Data

Change: 0.97%

Change: -0.01%

Change: 0.03%

Change: 1.03%

Change: -0.23%

Data supplied by Profile Data

Change: 0.00%

Change: 0.00%

Change: 0.00%

Change: 0.00%

Change: 0.00%

Data supplied by Profile Data