CAPTURING cruelty, both physical and emotional, in powerful prose that dances with the luminous intensity of a firefly is no mean feat. This is particularly so when the topic at hand — family and women abuse — so often attracts a bored societal yawn.

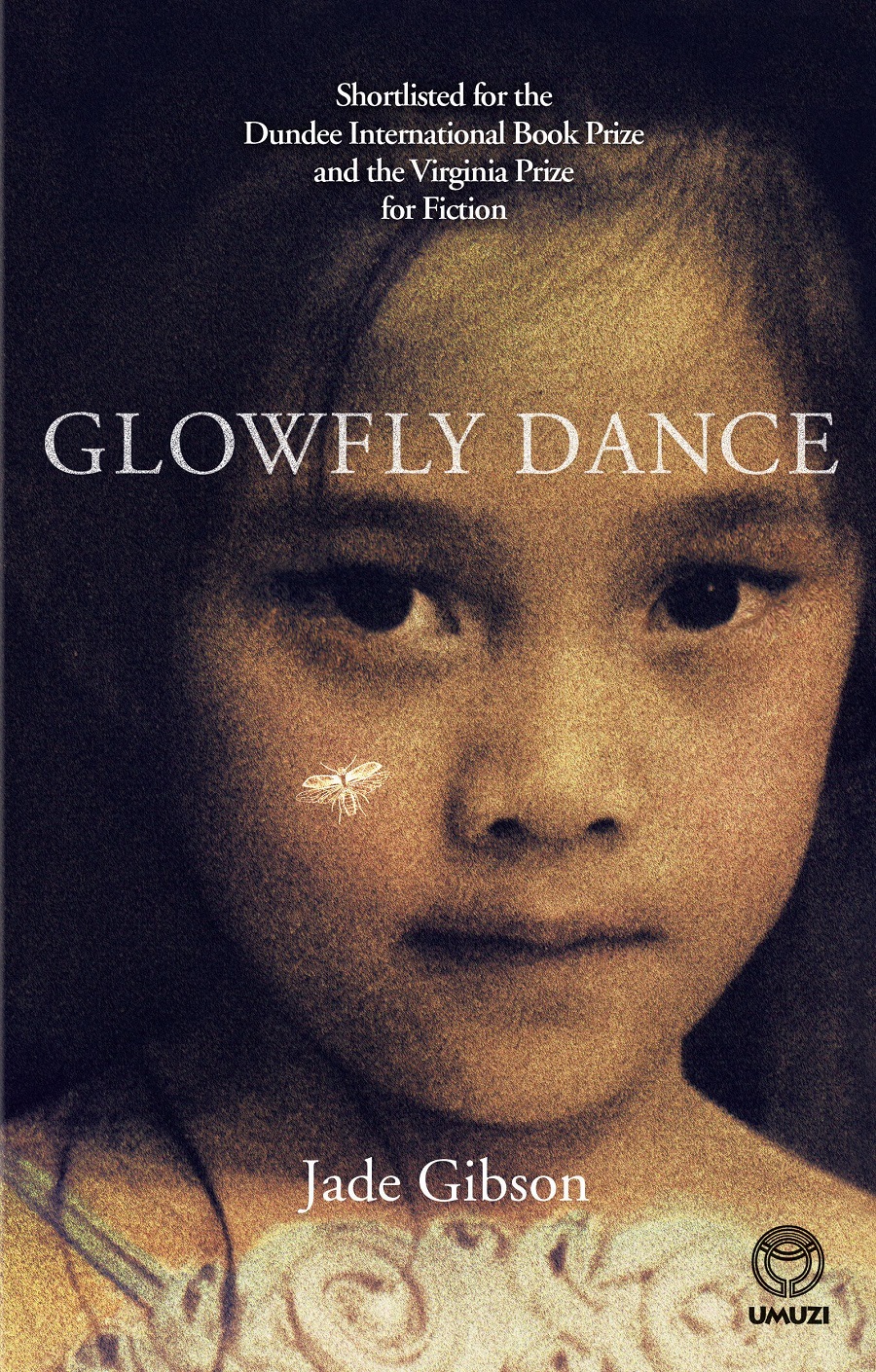

Yet this is what author Jade Gibson has managed with her debut Glowfly Dance, based on a true story. Acknowledgment of her achievement has come in the book being shortlisted for two international awards: the Dundee International Book Prize and the Virginia Prize for Fiction. Both are British prizes for unpublished novels, with the latter created in memory of Virginia Woolf.

Gibson’s tale is written through the eyes, "slanted like the wings of gulls flying in the sky", of a child who has never known her father.

Gibson, who has a doctorate in anthropology and teaches at the universities of Cape Town and the Western Cape, says she wrote the book in the present tense because it is "the only tense children know".

...

WE JOIN the narrator, Mai, in an initially happy Scots childhood when she is three and learns to dance standing on her grandfather’s feet. She and her small sister Amy don’t miss having daddies because they don’t know what they are.

Amy’s father divorces her and Mai’s mother, Elizabeth, when he goes to SA to look for work. Mai’s half-Filipino ancestry would bar her entry to the apartheid state, he says.

Soon, the sinister Rashid with eyes of "pure evil" weds their mother. A brother, Matti, and sister, Babs, are born. When they are still tiny, he abducts them to his home in Morocco, where his brothers hold high positions in the army and police.

Rashid returns to the UK with his children and his physical and mental abuse of Mai continues, as does his emotional and physical torture of the four children’s mother.

When she realises Mai is being set up for sexual predation by Rashid, Elizabeth tells social workers she can take no more.

A small van, protected by policemen, pulls up outside Mai and Amy’s school one day, and they are hurriedly bundled into it with their mother, thumb-sucking Matti and babe-in-arms Babs. Hours later, shocked and bewildered, but glad that they "are running away from Dad", the woman and children arrive at a home for battered wives, one of only two in England back then.

They join other mothers and children in a house where nobody enters through the front door. The back entrance is barred and bolted with access via a code. Rashid is committed to a mental institution for three years.

...

THREE months later, he is out and has tracked down Mai’s family, convincing his wife that he is a changed man with an excellent job and a promising new life awaiting them in Libya. She agrees to return to him.

Within months, however, Rashid is worse than ever. Now he targets his biological children, psychologically torturing Matti and beginning to groom Babs sexually.

Once again Elizabeth flees, her life on the line as several times he tries to kill her. But in a strange land, she can find refuge with a woman friend only for herself, Mai and Amy.

When Elizabeth hears that Rashid has little Babs sleeping in his bed, she fears the worst. She obtains a court order to set up a meeting, with police protection, with her children and Rashid. But on the day set for the confrontation, the police cannot provide an escort because "no one is free".

Despite Mai’s and Amy’s vociferous protests ringing in her ears, the desperately worried Elizabeth returns to the family home to see for herself what is going on.

Matti, we learn from Mai, sees his father kill their mother. Later, in the court case in which Rashid is tried for murder, the youngster takes to the stand to testify on the act, because he is told that it will convict his father.

Elizabeth is buried in an unmarked grave, the ultimate symbol of her invisibility as a battered woman.

Horrendously, Rashid is acquitted and, even worse, is allowed to keep Matti and Babs. They all disappear from Mai’s and Amy’s life.

Halfway through our interview, Gibson reveals that she is Mai, and has been writing this book since she was eight years old. "It’s a form of release. When people ask about my past, I find it almost impossible to relate so complex a matter. Maybe by putting readers into the body of this girl, so they can feel what she feels, they will understand her experience."

Gibson hopes this may lead to a change in approach to battered women and their families. "Society helps these dangerous men get away with really terrible things. So many children are orphaned."

...

STUDIES show that in SA, a woman dies every six hours at the hands of her male partner. In the US, the most dangerous place for a woman to be is in her home.

"I think my mother went back to Rashid, as do so many battered women, because she thought there was a glimmer of hope that he would stop the abuse. She weighed this hope against the certainty that he would find her again and she’d lose her children or her life."

Gibson, now in her forties, notes that "something like 70% of women who are in the process of leaving their (abusive) partners are killed".

The orphaned Gibson lived with foster families in England and came to SA, "for family reasons and to do my PhD".

Glowfly Dance is her life’s work, "in spite of my being petrified when it was published. It’s the scariest thing I’ve done."

All names and places have been changed for protection.

She emphasises that the book is not about creating a profile for her, "but to explain what is going on in abusive homes from the inside".

People tell Gibson her book is harrowing and beautiful. "The beauty is that I am here. I have a PhD. I have survived."

She is working on a sequel at her publisher’s insistence.

You won’t yawn about battered women after reading a book that is poetry, a thriller and a paean to their desperate resilience.

Jade Gibson tells the harrowing tale of her childhood. Picture: JURGEN MARX

CAPTURING cruelty, both physical and emotional, in powerful prose that dances with the luminous intensity of a firefly is no mean feat. This is particularly so when the topic at hand — family and women abuse — so often attracts a bored societal yawn.

Yet this is what author Jade Gibson has managed with her debut Glowfly Dance, based on a true story. Acknowledgment of her achievement has come in the book being shortlisted for two international awards: the Dundee International Book Prize and the Virginia Prize for Fiction. Both are British prizes for unpublished novels, with the latter created in memory of Virginia Woolf.

Gibson’s tale is written through the eyes, "slanted like the wings of gulls flying in the sky", of a child who has never known her father.

Gibson, who has a doctorate in anthropology and teaches at the universities of Cape Town and the Western Cape, says she wrote the book in the present tense because it is "the only tense children know".

...

WE JOIN the narrator, Mai, in an initially happy Scots childhood when she is three and learns to dance standing on her grandfather’s feet. She and her small sister Amy don’t miss having daddies because they don’t know what they are.

Amy’s father divorces her and Mai’s mother, Elizabeth, when he goes to SA to look for work. Mai’s half-Filipino ancestry would bar her entry to the apartheid state, he says.

Soon, the sinister Rashid with eyes of "pure evil" weds their mother. A brother, Matti, and sister, Babs, are born. When they are still tiny, he abducts them to his home in Morocco, where his brothers hold high positions in the army and police.

Rashid returns to the UK with his children and his physical and mental abuse of Mai continues, as does his emotional and physical torture of the four children’s mother.

When she realises Mai is being set up for sexual predation by Rashid, Elizabeth tells social workers she can take no more.

A small van, protected by policemen, pulls up outside Mai and Amy’s school one day, and they are hurriedly bundled into it with their mother, thumb-sucking Matti and babe-in-arms Babs. Hours later, shocked and bewildered, but glad that they "are running away from Dad", the woman and children arrive at a home for battered wives, one of only two in England back then.

They join other mothers and children in a house where nobody enters through the front door. The back entrance is barred and bolted with access via a code. Rashid is committed to a mental institution for three years.

...

THREE months later, he is out and has tracked down Mai’s family, convincing his wife that he is a changed man with an excellent job and a promising new life awaiting them in Libya. She agrees to return to him.

Within months, however, Rashid is worse than ever. Now he targets his biological children, psychologically torturing Matti and beginning to groom Babs sexually.

Once again Elizabeth flees, her life on the line as several times he tries to kill her. But in a strange land, she can find refuge with a woman friend only for herself, Mai and Amy.

When Elizabeth hears that Rashid has little Babs sleeping in his bed, she fears the worst. She obtains a court order to set up a meeting, with police protection, with her children and Rashid. But on the day set for the confrontation, the police cannot provide an escort because "no one is free".

Despite Mai’s and Amy’s vociferous protests ringing in her ears, the desperately worried Elizabeth returns to the family home to see for herself what is going on.

Matti, we learn from Mai, sees his father kill their mother. Later, in the court case in which Rashid is tried for murder, the youngster takes to the stand to testify on the act, because he is told that it will convict his father.

Elizabeth is buried in an unmarked grave, the ultimate symbol of her invisibility as a battered woman.

Horrendously, Rashid is acquitted and, even worse, is allowed to keep Matti and Babs. They all disappear from Mai’s and Amy’s life.

Halfway through our interview, Gibson reveals that she is Mai, and has been writing this book since she was eight years old. "It’s a form of release. When people ask about my past, I find it almost impossible to relate so complex a matter. Maybe by putting readers into the body of this girl, so they can feel what she feels, they will understand her experience."

Gibson hopes this may lead to a change in approach to battered women and their families. "Society helps these dangerous men get away with really terrible things. So many children are orphaned."

...

STUDIES show that in SA, a woman dies every six hours at the hands of her male partner. In the US, the most dangerous place for a woman to be is in her home.

"I think my mother went back to Rashid, as do so many battered women, because she thought there was a glimmer of hope that he would stop the abuse. She weighed this hope against the certainty that he would find her again and she’d lose her children or her life."

Gibson, now in her forties, notes that "something like 70% of women who are in the process of leaving their (abusive) partners are killed".

The orphaned Gibson lived with foster families in England and came to SA, "for family reasons and to do my PhD".

Glowfly Dance is her life’s work, "in spite of my being petrified when it was published. It’s the scariest thing I’ve done."

All names and places have been changed for protection.

She emphasises that the book is not about creating a profile for her, "but to explain what is going on in abusive homes from the inside".

People tell Gibson her book is harrowing and beautiful. "The beauty is that I am here. I have a PhD. I have survived."

She is working on a sequel at her publisher’s insistence.

You won’t yawn about battered women after reading a book that is poetry, a thriller and a paean to their desperate resilience.

Change: 0.80%

Change: 0.61%

Change: -0.25%

Change: 0.13%

Change: 4.02%

Data supplied by Profile Data

Change: 1.13%

Change: 0.37%

Change: 0.80%

Change: 0.00%

Change: 0.33%

Data supplied by Profile Data

Change: -2.03%

Change: -1.51%

Change: -1.45%

Change: -2.26%

Change: -0.91%

Data supplied by Profile Data

Change: 0.07%

Change: 3.71%

Change: 2.65%

Change: 3.36%

Change: 4.99%

Data supplied by Profile Data