RACIST ranting — explicit, alarming and the hot topic of the day — is somewhat surprisingly not the main focus in Run Racist Run, the third book from author, philosopher and debater Eusebius McKaiser.

He addresses the invective of the Steve Hofmeyr and Penny Sparrow types, but the author’s primary targets are English-speaking white South Africans, "who self-identity as liberal or progressive and see themselves as allies of black people".

They think of themselves, "as decent, and a completed project", he says. For them, he says, it will be a shock to learn "that they have work to do".

Many of his friends in the media, or those who studied with him at the universities of Rhodes in Grahamstown and Oxford in England (he didn’t graduate from the latter), fall into this category. He expects they will say with an injured air: "F… you Eusebius, we came to your launch, we’re buying the book, we’re fighting with our racist cousin at the family braai."

The book is a collection of essays. McKaiser argues that victims of racism have a right to display anger, and says he is not grateful to those who want to work on their bigotry. "You are simply doing what is morally decent," he says. He is also amazed that a phenomenon as common as racism can still be so poorly understood.

In one chapter he skewers, "the pathetic demands of some white liberals who ask black people to tell them how they can undo the legacy of the past. They must go it alone."

It is the liberals, "with unearned privileges, sometimes a lack of awareness or an unconscious bias", whom he concentrates on the most. "This was not by design," he says. "I wrote the essays and this is how the book turned out."

He has written off locking horns with blunt racists, "who won’t read it anyway", preferring to engage with readers open to persuasion.

Some black readers have told him that the book, already in its second printing, gave them the language with which to articulate their angst and experiences of racism.

And, no, he is not surprised by the seeming upsurge of racism in 2016. Asked "But why now?" he responds that it is neither exceptional nor new.

"We have never dealt with our racism as a society, in spite of what President Jacob Zuma said to the contrary recently. The prominence given to these incidents will lull us into a belief that we’re dealing with a limited-edition racist. We are not."

...

MCKAISER wants South Africans to open themselves to noticing the daily racism that exists in every level of society and not just when the k-word is used or black people are beaten up.

However, he makes it clear that there’s no such thing as subtle racism, "as victims of it know all too well. All racism is inherently violent."

In his first book, A Bantu in My Bathroom, he focused on overt racist actions. In this one, he examines attitudinal racism, and its physical expression. In so doing, McKaiser has not only targeted liberals, he also writes that, "xenophobia is not disconnected from racism".

Xenophobia and Afrophobia (a fear of other Africans) are intimately connected, he says, to the legacies of colonialism and racism. Even if white people disappeared, "we would still not be free of racism’s history, one we cannot undo".

He posits that black people have become clones of racists, "who taught us how to hate on the basis of arbitrary differences between us".

Other topics the author addresses include the black middle class being more upset when let down by white liberals than by outright racists.

"The approval of liberal whites secretly matters for many black middle-class people," he adds.

He challenges two notions about the so-called born free generation — that they are blind to race, and that they are politically apathetic.

He also devotes several pages to "our black, taxed lives", explaining that the first-generation black lawyer or accountant pays for all her siblings’ education and otherwise supports her extended family, putting off personal financial advancement.

Violence against women is a strong thread throughout the book. Misogyny, like racism, occurs daily yet attracts attention only when a woman is killed.

He devotes one chapter to coloured people, explaining he does not know how to write about them, nor does he find them interesting in spite of his being born coloured.

"I am black and I self-identify politically as black. I am also coloured. Yes, it is confusing."

...

HE IS not surprised that coloured voters are generally "floating voters", not being at home anywhere politically.

He is doubtful that his book, with its challenging, opportunistic title and thought-provoking content, might help to move SA forward and away from racism. "This won’t happen anytime soon. There is a direct correlation between racism decreasing and the rate at which our economy becomes a more just and equitable one."

McKaiser believes that in SA’s capitalist society, it is only when black people have work and money that they will feel a sense of self-worth, and in psychological terms, "self-actualise".

The prospects for that are low, "because the drivers of racism are high unemployment, deep levels of poverty, income inequality and the education crisis".

The book has been deliberately written in an easily accessible and chatty style so anyone can absorb it. It almost comes across as a debate, although the author has kept the often-lofty words he uses in those to a minimum.

McKaiser is so alarmed by racism that he deferred another book he was working on to pen this one.

He questions and challenges himself throughout and hopes readers will do the same.

I did, and while not agreeing with all of it, I reassessed several of my beliefs.

There is a direct correlation between racism decreasing and the rate at which our economy becomes a more just and equitable one.

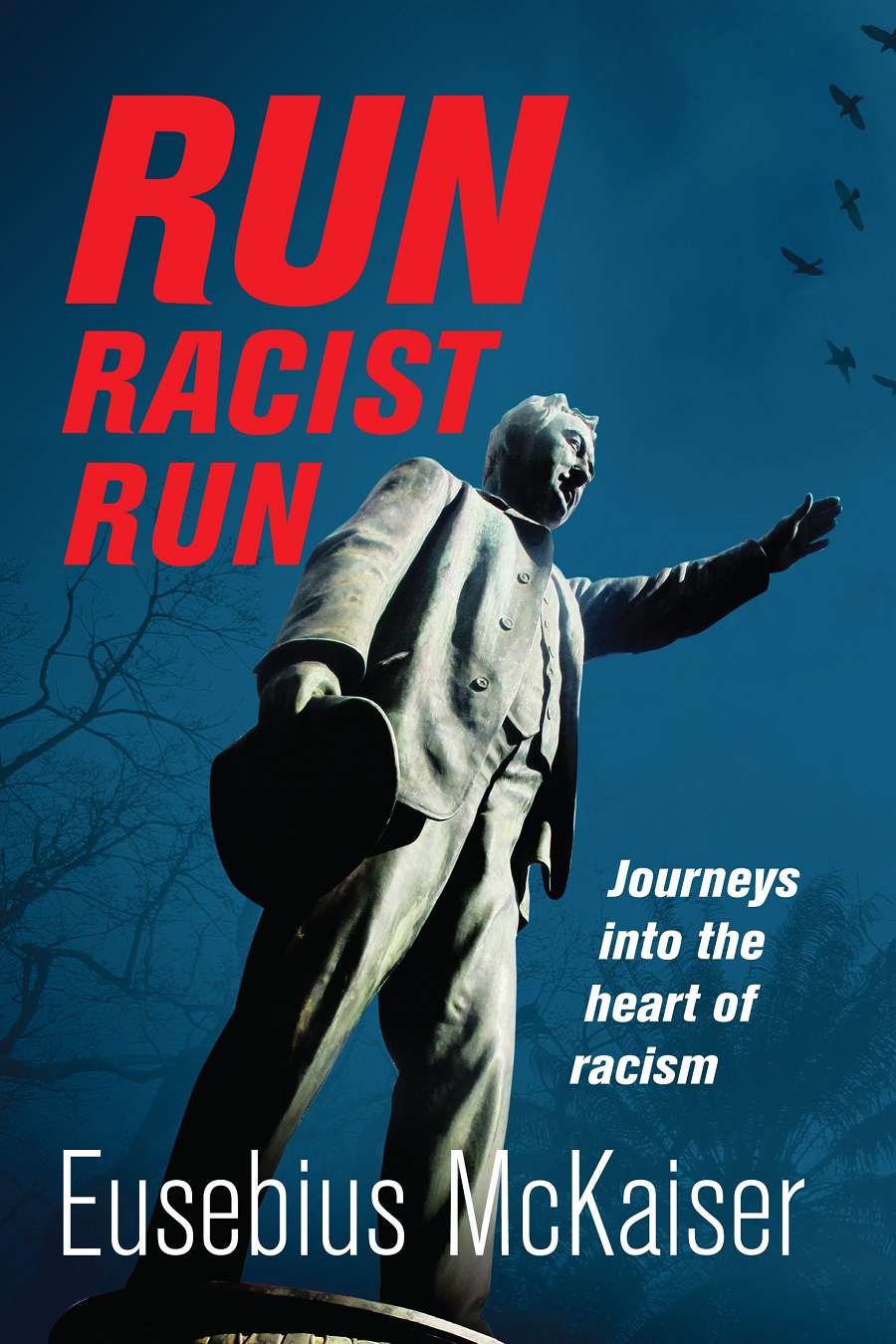

Eusebius McKaiser’s third book dissects the unearned privileges that even well-meaning white South Africans take for granted, and looks into misogyny and xenophobia. Picture: SUPPLIED

RACIST ranting — explicit, alarming and the hot topic of the day — is somewhat surprisingly not the main focus in Run Racist Run, the third book from author, philosopher and debater Eusebius McKaiser.

He addresses the invective of the Steve Hofmeyr and Penny Sparrow types, but the author’s primary targets are English-speaking white South Africans, "who self-identity as liberal or progressive and see themselves as allies of black people".

They think of themselves, "as decent, and a completed project", he says. For them, he says, it will be a shock to learn "that they have work to do".

Many of his friends in the media, or those who studied with him at the universities of Rhodes in Grahamstown and Oxford in England (he didn’t graduate from the latter), fall into this category. He expects they will say with an injured air: "F… you Eusebius, we came to your launch, we’re buying the book, we’re fighting with our racist cousin at the family braai."

The book is a collection of essays. McKaiser argues that victims of racism have a right to display anger, and says he is not grateful to those who want to work on their bigotry. "You are simply doing what is morally decent," he says. He is also amazed that a phenomenon as common as racism can still be so poorly understood.

In one chapter he skewers, "the pathetic demands of some white liberals who ask black people to tell them how they can undo the legacy of the past. They must go it alone."

It is the liberals, "with unearned privileges, sometimes a lack of awareness or an unconscious bias", whom he concentrates on the most. "This was not by design," he says. "I wrote the essays and this is how the book turned out."

He has written off locking horns with blunt racists, "who won’t read it anyway", preferring to engage with readers open to persuasion.

Some black readers have told him that the book, already in its second printing, gave them the language with which to articulate their angst and experiences of racism.

And, no, he is not surprised by the seeming upsurge of racism in 2016. Asked "But why now?" he responds that it is neither exceptional nor new.

"We have never dealt with our racism as a society, in spite of what President Jacob Zuma said to the contrary recently. The prominence given to these incidents will lull us into a belief that we’re dealing with a limited-edition racist. We are not."

...

MCKAISER wants South Africans to open themselves to noticing the daily racism that exists in every level of society and not just when the k-word is used or black people are beaten up.

However, he makes it clear that there’s no such thing as subtle racism, "as victims of it know all too well. All racism is inherently violent."

In his first book, A Bantu in My Bathroom, he focused on overt racist actions. In this one, he examines attitudinal racism, and its physical expression. In so doing, McKaiser has not only targeted liberals, he also writes that, "xenophobia is not disconnected from racism".

Xenophobia and Afrophobia (a fear of other Africans) are intimately connected, he says, to the legacies of colonialism and racism. Even if white people disappeared, "we would still not be free of racism’s history, one we cannot undo".

He posits that black people have become clones of racists, "who taught us how to hate on the basis of arbitrary differences between us".

Other topics the author addresses include the black middle class being more upset when let down by white liberals than by outright racists.

"The approval of liberal whites secretly matters for many black middle-class people," he adds.

He challenges two notions about the so-called born free generation — that they are blind to race, and that they are politically apathetic.

He also devotes several pages to "our black, taxed lives", explaining that the first-generation black lawyer or accountant pays for all her siblings’ education and otherwise supports her extended family, putting off personal financial advancement.

Violence against women is a strong thread throughout the book. Misogyny, like racism, occurs daily yet attracts attention only when a woman is killed.

He devotes one chapter to coloured people, explaining he does not know how to write about them, nor does he find them interesting in spite of his being born coloured.

"I am black and I self-identify politically as black. I am also coloured. Yes, it is confusing."

...

HE IS not surprised that coloured voters are generally "floating voters", not being at home anywhere politically.

He is doubtful that his book, with its challenging, opportunistic title and thought-provoking content, might help to move SA forward and away from racism. "This won’t happen anytime soon. There is a direct correlation between racism decreasing and the rate at which our economy becomes a more just and equitable one."

McKaiser believes that in SA’s capitalist society, it is only when black people have work and money that they will feel a sense of self-worth, and in psychological terms, "self-actualise".

The prospects for that are low, "because the drivers of racism are high unemployment, deep levels of poverty, income inequality and the education crisis".

The book has been deliberately written in an easily accessible and chatty style so anyone can absorb it. It almost comes across as a debate, although the author has kept the often-lofty words he uses in those to a minimum.

McKaiser is so alarmed by racism that he deferred another book he was working on to pen this one.

He questions and challenges himself throughout and hopes readers will do the same.

I did, and while not agreeing with all of it, I reassessed several of my beliefs.

There is a direct correlation between racism decreasing and the rate at which our economy becomes a more just and equitable one.

Change: -1.54%

Change: -1.49%

Change: -2.02%

Change: -0.73%

Change: -4.01%

Data supplied by Profile Data

Change: 0.10%

Change: -0.45%

Change: -1.54%

Change: 0.00%

Change: -0.64%

Data supplied by Profile Data

Change: 0.37%

Change: 0.23%

Change: 0.21%

Change: -0.15%

Change: 0.12%

Data supplied by Profile Data

Change: -0.23%

Change: -0.21%

Change: -0.07%

Change: -0.69%

Change: -0.32%

Data supplied by Profile Data