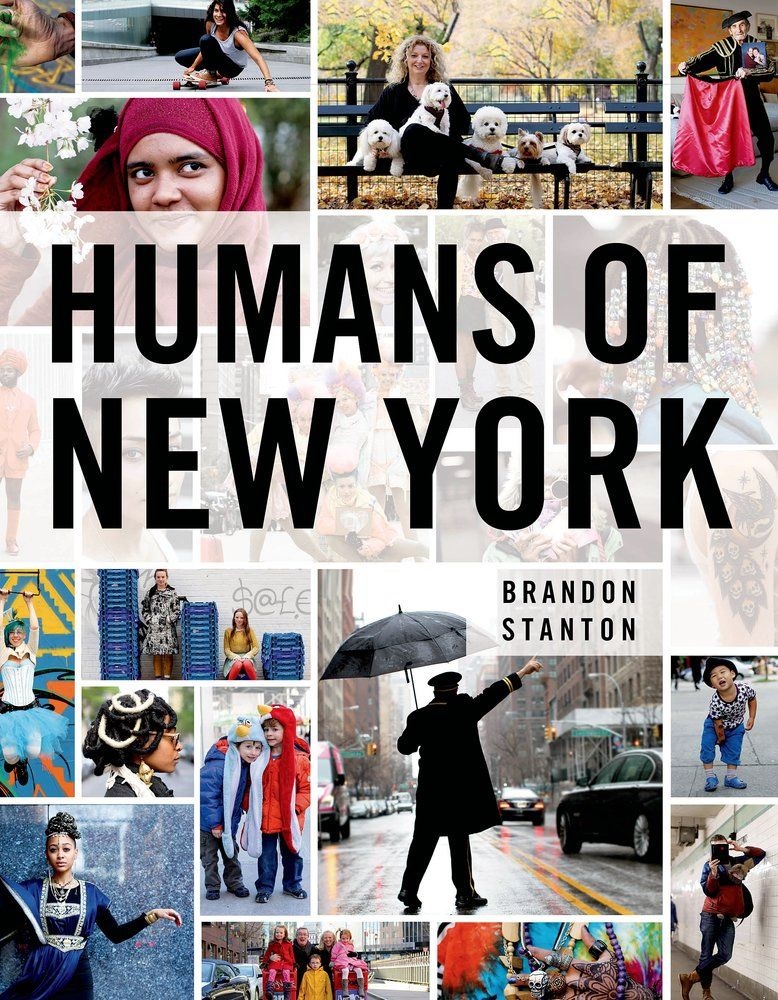

BOOK REVIEW: Humans of New York

by Karin Schimke,

2016-01-15 06:04:52.0

EMPATHY as a field of scientific study — rather than a touchy-feely religion-infused area of undefinables — is fascinating. Turns out we’re hardwired to "feel with" or "feel into" and that it has an important social function.

One could even go so far as to say that the old notions of "dog eats dog" and "survival of the toughest" are losing, among the world’s thinkers, some cachet as the primary way in which we survive. Empathy, in fact, is thought to be integral to social survival.

Brandon Stanton steps into this growing area of scientific interest. He’s not a scientist. Neither is he, by training, a photographer, storyteller, social worker or psychologist. But within a mere five years, he has provided possibly the most visible, most engaging and most talked about empathy experiments the world has ever seen.

Stanton is the creator of Humans of New York (Hony), a blog started in 2010, in which he planned to photograph 10,000 New Yorkers and plot their photos on a map.

The idea morphed away from the initial goal as Stanton started collecting quotes and stories from his subjects.

There are now almost 16.5-million followers of Hony on Facebook and 4.4-million on Instagram. The "humans of" has had spin-offs around the world, but nothing so far has had the effect that Hony has had in terms of spread, popularity and social muscle.

Hony, for instance, has raised millions upon millions of dollars for a variety of causes and Stanton has met US President Barack Obama and travelled to Pakistan, Iran, Iraq, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (among other countries). This year, he went to Europe to record the stories of migrants and refugees seeking asylum from their devastated homelands.

None of this is what Stanton set out to do. He simply wanted to escape having to do a job he disliked (bond trading) and find a way to make his time his own and do what he really liked doing.

Humans of New York Stories is his third book. The first one (2013) spent 29 weeks on the New York Times Bestsellers list.

What chord has Stanton struck? One commentator has gone to great lengths to explain that Stanton’s work is emotionally manipulative, that all his subjects end up being "same-ish" and that they conform to stereotypes.

I find that hard to swallow as I page through this 400-plus-page book of recent humans and their stories. Each story is so entirely unexpected and at the same time recognisable — which is where the magic mushroom of empathy can be plucked. Empathy does not require you to obviously resemble another person in looks or circumstance.

Empathy is just that sweet spot created by stories that are at once narrowly individual and peculiarly universal.

Of course, one can be cynical about Hony, but my sense is that even as it is imbued with a schmaltzy sheen because of how it lands so softly and welcomingly for so many millions of people, it fulfils a human hankering towards what is "share-able", what is common, what is recognisable.

Stanton has an astonishing ability to "get the quote". The stories people share — from the mundane and prosaic to the disturbing, the hilarious, the thought-challenging, the ridiculous and the joyous — are never predictable.

In combination with the photographs, it provides a picture of a person that is at once exceedingly narrow (they become, for the viewer, just that one picture and that one story) and enormously vivid.

One must bear in mind — if you’re going to be crabby about Hony at all — that every person allows their picture to be taken and tells Stanton something of their own free will.

He is pointing a camera at them, not a gun, and every person participates freely in Stanton’s minuscule record of them. From years of journalism, I can attest to the fact that people do like to be seen, to be heard, to be reckoned. As much as empathy is part of the human story, so is the desire to "share my story".

Hony Stories is a production of high values, which reflects coffee-table book standards in a tome that is a bit more transportable. Although it is thick and heavy (thanks to the hard cover and the quality paper), it is not so unwieldy that it cannot be read in bed or on a park bench.

It is a book of value.

And Stanton, who has perhaps become the face of American do-goodery and feel-goodery in a way that might annoy some grumps, keeps — to my eye — an unobtrusive integrity, and demonstrates the power and thrall of empathy.

Picture: THINKSTOCK

EMPATHY as a field of scientific study — rather than a touchy-feely religion-infused area of undefinables — is fascinating. Turns out we’re hardwired to "feel with" or "feel into" and that it has an important social function.

One could even go so far as to say that the old notions of "dog eats dog" and "survival of the toughest" are losing, among the world’s thinkers, some cachet as the primary way in which we survive. Empathy, in fact, is thought to be integral to social survival.

Brandon Stanton steps into this growing area of scientific interest. He’s not a scientist. Neither is he, by training, a photographer, storyteller, social worker or psychologist. But within a mere five years, he has provided possibly the most visible, most engaging and most talked about empathy experiments the world has ever seen.

Stanton is the creator of Humans of New York (Hony), a blog started in 2010, in which he planned to photograph 10,000 New Yorkers and plot their photos on a map.

The idea morphed away from the initial goal as Stanton started collecting quotes and stories from his subjects.

There are now almost 16.5-million followers of Hony on Facebook and 4.4-million on Instagram. The "humans of" has had spin-offs around the world, but nothing so far has had the effect that Hony has had in terms of spread, popularity and social muscle.

Hony, for instance, has raised millions upon millions of dollars for a variety of causes and Stanton has met US President Barack Obama and travelled to Pakistan, Iran, Iraq, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (among other countries). This year, he went to Europe to record the stories of migrants and refugees seeking asylum from their devastated homelands.

None of this is what Stanton set out to do. He simply wanted to escape having to do a job he disliked (bond trading) and find a way to make his time his own and do what he really liked doing.

Humans of New York Stories is his third book. The first one (2013) spent 29 weeks on the New York Times Bestsellers list.

What chord has Stanton struck? One commentator has gone to great lengths to explain that Stanton’s work is emotionally manipulative, that all his subjects end up being "same-ish" and that they conform to stereotypes.

I find that hard to swallow as I page through this 400-plus-page book of recent humans and their stories. Each story is so entirely unexpected and at the same time recognisable — which is where the magic mushroom of empathy can be plucked. Empathy does not require you to obviously resemble another person in looks or circumstance.

Empathy is just that sweet spot created by stories that are at once narrowly individual and peculiarly universal.

Of course, one can be cynical about Hony, but my sense is that even as it is imbued with a schmaltzy sheen because of how it lands so softly and welcomingly for so many millions of people, it fulfils a human hankering towards what is "share-able", what is common, what is recognisable.

Stanton has an astonishing ability to "get the quote". The stories people share — from the mundane and prosaic to the disturbing, the hilarious, the thought-challenging, the ridiculous and the joyous — are never predictable.

In combination with the photographs, it provides a picture of a person that is at once exceedingly narrow (they become, for the viewer, just that one picture and that one story) and enormously vivid.

One must bear in mind — if you’re going to be crabby about Hony at all — that every person allows their picture to be taken and tells Stanton something of their own free will.

He is pointing a camera at them, not a gun, and every person participates freely in Stanton’s minuscule record of them. From years of journalism, I can attest to the fact that people do like to be seen, to be heard, to be reckoned. As much as empathy is part of the human story, so is the desire to "share my story".

Hony Stories is a production of high values, which reflects coffee-table book standards in a tome that is a bit more transportable. Although it is thick and heavy (thanks to the hard cover and the quality paper), it is not so unwieldy that it cannot be read in bed or on a park bench.

It is a book of value.

And Stanton, who has perhaps become the face of American do-goodery and feel-goodery in a way that might annoy some grumps, keeps — to my eye — an unobtrusive integrity, and demonstrates the power and thrall of empathy.

Change: 1.19%

Change: 1.36%

Change: 2.19%

Change: 1.49%

Change: -0.77%

Data supplied by Profile Data

Change: -0.08%

Change: 0.12%

Change: 1.19%

Change: 0.00%

Change: 0.10%

Data supplied by Profile Data

Change: 0.32%

Change: 0.38%

Change: 0.36%

Change: 0.22%

Change: 0.23%

Data supplied by Profile Data

Change: -0.02%

Change: -0.51%

Change: -0.19%

Change: -0.33%

Change: -0.15%

Data supplied by Profile Data