ANYONE wishing to counter the bleakness of Wednesday’s budget and feel wistful about the way things once were could start by reading the budget speech then finance minister Trevor Manuel delivered in February 2006.

The economy had grown 5% in 2005 and it was expected to continue growing at that pace for the foreseeable future. Commodity prices were reaching record highs, capital was flowing in, and SA was reaping the benefits of its tax-reform efforts and its success in bringing down debt levels and the cost of debt.

Mr Manuel could announce a R41bn revenue overrun and a budget deficit that had shrunk to 0.5% of gross domestic product (GDP), far below the 3.1% he had budgeted for just a year before. "The economic outlook is exceedingly favourable," Mr Manuel said in his inimitable way, as he upped spending, cut taxes — and proceeded to budget for a deficit of 1.5% for the next fiscal year (2006-07), falling to 1.2% in 2008-09.

In the event, even that proved to be too pessimistic, and 2006-07 turned out to be the first of two halcyon years in which SA ran a budget surplus but continued to boost spending, especially social spending, in real terms and to grant some generous tax concessions.

In retrospect, the budget surplus should have been much larger. Treasury officials at the time estimated that SA should have been running a surplus of 6% or more, reflecting cyclical (as opposed to structural) revenues of 6%-8%. That the revenue overruns were indeed purely cyclical and not more durable structural increases proved to be the case when the economy went into recession in 2008-09 and the deficit ballooned to that 6%-8% range.

There has been much debate about just how much of SA’s growth dividend at the time was thanks to its own efforts in opening up the economy and pursuing sound macroeconomic policies, and a good deal of it clearly was.

But, in retrospect, it is clear that the rising global tide over that period lifted all boats and SA sailed along with it.

Budgeting in the good times is in many ways more difficult that it is when times are tough, because when the money is rolling in everyone wants their share and it is very difficult for a finance minister to say no, especially a finance minister in a developing democracy such as SA, with its pressing social and economic needs.

So while it may be easy with hindsight to argue that Mr Manuel and his team should have budgeted for larger surpluses, at the time it was a huge stretch politically to make the case even for small surpluses.

In his February 2007 budget speech, Mr Manuel hailed SA’s economic good fortune, which was projected to continue with the commodity price rally continuing and economic growth expected to average just more than 5% a year over the following three years. Revenue for the 2006-07 fiscal year had come in R29bn over budget, so the outcome for the year was a R5bn surplus rather than the projected deficit.

This time, Mr Manuel budgeted for a fiscal surplus — of 0.6% of GDP for 2007-08, which came out at 1% in the end, thanks in part to yet another revenue overrun, of R15bn.

By the time of his budget speech in early 2008, the global storm clouds were just starting to gather, and he did warn that the course ahead would be somewhat tougher.

But the fiscal stance SA had adopted would help it weather the global storm, he said, and the budget he tabled not only pencilled in a 1% surplus for the 2008-09 fiscal year, but saw the surpluses continuing, at about 0.7% a year, over the following three years — all while the government continued to grow spending by 6% in real, inflation-adjusted terms.

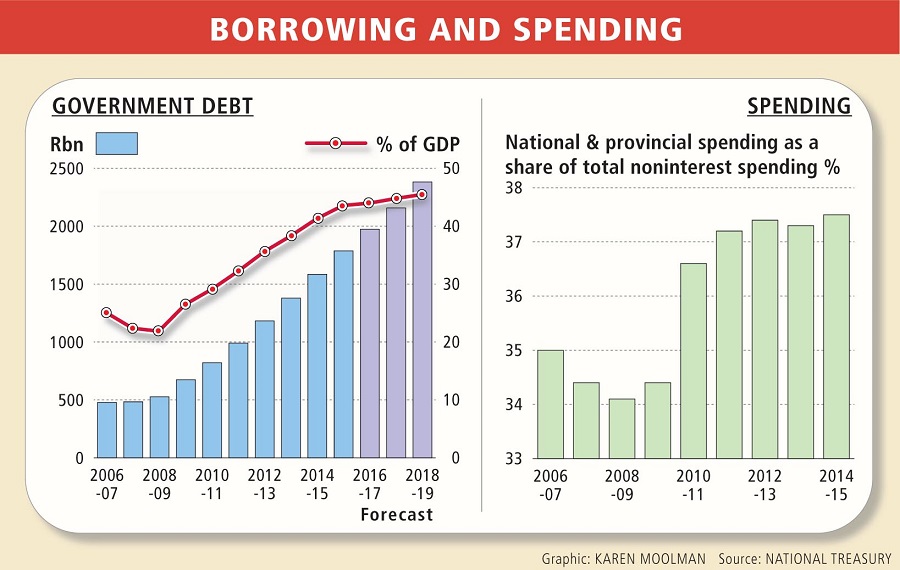

The government debt ratio was projected to fall to just 16% of GDP by 2011. We can but wish that it had. For when Mr Manuel came to table what turned out to be his last budget speech, not long before the 2009 elections, he had to announce: "The storm that we spoke of last year has broken and it is more severe than anyone anticipated."

Presciently, he commented, too, "In a very short period, what started off as a financial crisis may become a second great depression."

It did not quite show in the numbers yet — SA’s economic growth rate had slowed to 3.1% for 2008 and the budget outcome was a small deficit, with revenue having fallen about R14bn short of budget.

But the public debt ratio had fallen to 23% of GDP, down from 48% in 1996, and though Mr Manuel warned against running up debt and imposing on future generations the burden of having to repay it with interest, he emphasised that SA was able to run a countercyclical fiscal stimulus on the strength of the secure and sustainable fiscal policies it had put in place.

With the economy at that stage still expected to grow 1.2% in 2009, he budgeted for strong real spending growth and a budget deficit of 3.8%, which would fall to 1.9% by 2011-12, when growth was expected to pick up again to the 4% range.

Pity Finance Minister Pravin Gordhan, who never again had it that good. Based on his 2009 and December 2015 record, Mr Gordhan seems to be the guy who is appointed finance minister only when there is real trouble in the economy. In 2009 the economy was headed into recession by the time President Jacob Zuma put him in place to deal with the crisis.

Fortunately, he inherited the fiscal space that had been created in the Manuel era, so SA could spend its way out of recession, which was fairly shallow in our case. Unfortunately, it’s clear with hindsight that the space he inherited was not nearly enough, nor did the government use it in the way it should have. As it turned out, the economy never did return to the 4% growth it had averaged between 2000 and 2008. For the past three years, it has not managed to hit even 2% and, as a Treasury presentation put it last year, "A structural deficit has now become entrenched."

While Mr Manuel had presided over a virtuous cycle in which the fiscal balances became better and better and the debt ratio and debt-servicing costs kept falling, Mr Gordhan’s first term as finance minister between 2009 and 2014 saw the public debt and its cost sharply rising.

It would be hard to find anyone who would argue that he was wrong to pursue a countercyclical fiscal policy stance that would support the economy and underpin living standards, especially for poor people, through the crisis. But a few things went wrong.

One was that the global economy never recovered from the crisis.

Advanced countries’ expansive monetary policies and continued strong growth in China meant that SA and other emerging markets did have a halcyon few post-crisis years in which capital flowed inwards in search of higher yields and commodity prices boomed, but by 2014 it was all coming apart and the turbulence in commodity and financial markets only became worse.

The second problem for SA was that while the global uptick between 2010 and 2013, along with the fiscal stimulus and the 2010 Soccer World Cup boost, may have given an illusion that the economy was not that bad, the underlying structural factors were becoming worse, with little in government economic policy to attract investment or enhance the economy’s longer-term growth potential. Once the commodities and capital booms ended, it was the proverbial case of the tide going out and SA’s economic growth nakedness being revealed.

That in turn related to a third problem, possibly the most significant one from a fiscal point of view, which was that we had largely the wrong kind of fiscal stimulus. Ideally, a government would run up the deficit and the debt level to help the economy through a temporary trough — but in a way that would help it to enhance its growth potential more permanently for future years.

Investing in infrastructure and in skills would be a major way to do that, and the argument for deficit spending at the time SA went into the crisis was that the government would spend to cushion the poor, as well as to support the expansion of SA’s growth potential, making capital spending a priority, with about R800bn in infrastructure investment on the drawing board. That did not happen.

Instead, too much of the spending increase went on the public sector payroll, thanks initially to pay increases granted at the height of the crisis in 2009-10 that were above inflation and more than the Treasury had agreed, as well as strong growth in the number of public servants.

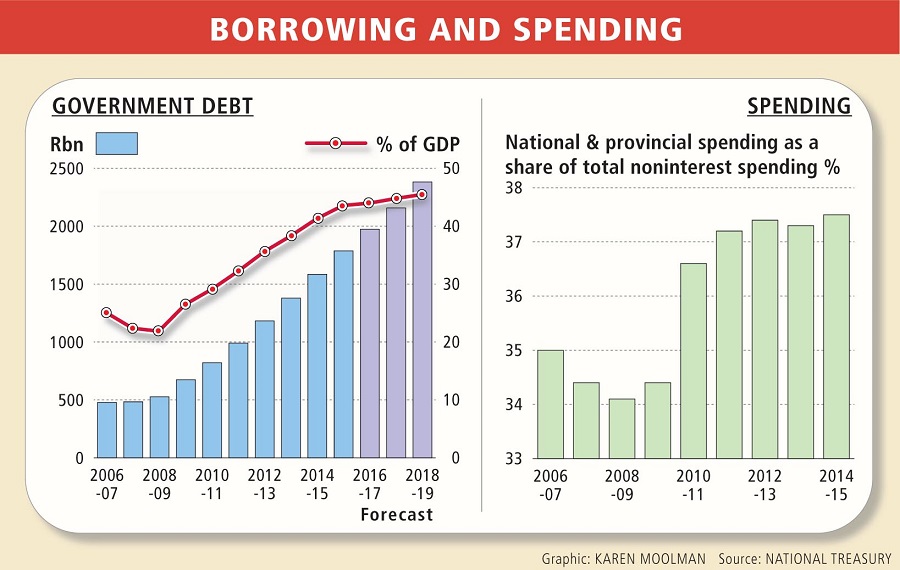

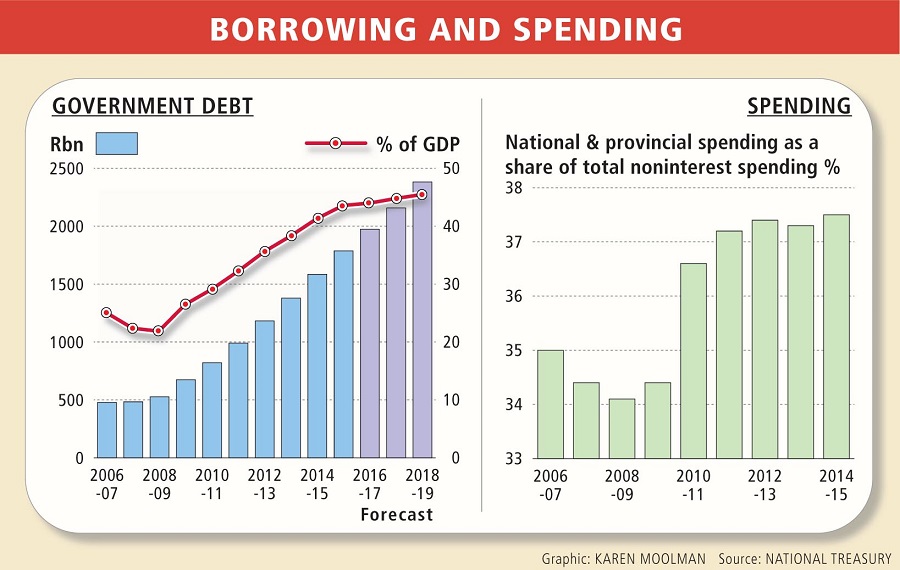

In the five years to 2011, the size of the public sector payroll doubled, to take up almost 40% of noninterest spending.

In his 2010 budget speech, Mr Gordhan announced revenue had fallen R69bn short of budget estimates, with the economy shrinking 1.8% during 2009. The budget balance, he pointed out, had gone from a 1% surplus to a 7.3% deficit in just two years. But that had cushioned the economy against a larger decline in output and jobs, and had ensured that the government could maintain spending on social and economic services despite the decline in revenue.

With growth expected to pick up as the world recovered from recession, Mr Gordhan pencilled in slower but still significant real growth of 2% in government spending and higher borrowing in what he said was a temporary solution. The public debt ratio was seen blowing out to 40% by 2013 before stabilising last year.

It was not looking too bad by the time of his 2011 budget speech. Economic growth had picked up to 2.8% in 2010 and tax revenue had once again come in about 12% above budget. The original budget deficit estimate of 6.2% was revised to a less steep 5.3%, and the budget framework envisaged this falling to 4.8% and 3.8% in the following two years, with economic growth seen picking up to more than 4% in 2012 and 2013.

To his credit, Mr Gordhan had managed to extract about R30bn of savings from government departments. He used the budget speech to announce new measures to curb irregularities in public procurement and to prevent corruption.

There were concerns, however, about the growing level of government debt, which was heading towards a projected R1.3-trillion by 2013-14 — more than double the level at the end of 2008-09 — with debt costs now the fastest rising budget item. Mr Gordhan announced that guidelines had been proposed on long-term fiscal sustainability and debt management. He also expressed concern about the effect of the 2010 public sector pay settlement and the rapid rise in the public sector salary bill, which had doubled over five years.

There was much in his 2010 and 2011 budget speeches about the government’s commitment to a new growth path and a higher economic growth rate. By the time of the 2012 budget, the third of the Zuma administration, SA’s growth story was still seen as being on the rise, despite a global environment that Mr Gordhan described as "hugely uncertain", with the economy having grown 3% a year on average since 2009 — even though the 2012 growth rate was expected to fall to 2.7% before recovering.

"SA’s finances are in good health," Mr Gordhan told Parliament. Tax revenues had recovered since the crisis and the deficit was budgeted at 4.6% of GDP for 2012-13 but was planned to return to 3% in 2014-15, with the public debt ratio stabilising at about 38% of GDP.

It was in that budget that Mr Gordhan introduced an expenditure ceiling, which would cap government spending in nominal terms over three years — but the move did not receive a lot of emphasis in the speech, and attracted hardly any notice at the time.

It gained a higher profile the next year, with the extent of the fiscal challenge and SA’s growth challenge becoming ever more evident. "SA’s economic outlook is improving but requires that we actively pursue a different trajectory if we are to address the challenges ahead," Mr Gordhan said in his 2013 budget speech, which had the promise of the National Development Plan (NDP), which the Cabinet had approved. The speech had the NDP as its point of departure, Mr Gordhan emphasised.

With growth of only 2.5% in 2012, the budget deficit had come out rather higher than anticipated, at 5.2% for 2012-13, and was seen falling to 3.1% in 2015-16, but growth prospects had weakened over the next three years, Mr Gordhan said.

Real growth in government spending had been trimmed back to 2.3%. And there was a strong emphasis again on getting value for the money government spends and curbing corruption, but by now Mr Gordhan was becoming more despondent, it seemed, about how endemic it had become. Speaking of efforts to get value for money, he said, "Let me be frank. This is a difficult task, with too many points of resistance."

His 2014 budget speech, Mr Gordhan’s last before Mr Zuma unexpectedly replaced him with Nhlanhla Nene after the elections, was an even more sober affair. Mr Gordhan used the speech to recount what had been achieved since the crisis, with government spending having doubled in real terms over the past decade, and 57% of the budget now going on the "social wage". The government had borrowed R1-trillion over the past five years, he noted, as he again pushed the targets for stabilising the debt ratio outwards and upwards, with net debt now expected to stabilise at 45% only in 2016-17.

But he was still relatively optimistic about economic growth, which was projected to increase from 2.7% to 3.5% this year. We wish. Now we know the economy will not get close to even 1% this year. And by the time Mr Nene presented his first — and, as it turned out, his only — February budget speech last year, there was no getting away from the fact that growth estimates had consistently been undershot and debt stabilisation targets overshot.

Presenting his February budget speech a year ago, a realistic Mr Nene came straight to the point: "Today’s budget is constrained by the need to consolidate our public finances in the context of slower growth and rising debt."

It was, arguably, too little too late to prevent the rating agencies gearing up to downgrade. And Mr Nene’s abrupt firing by Mr Zuma in December did nothing to improve SA’s already damaged fiscal credibility.

-

Pravin Gordhan. Picture: BLOOMBERG/JASON ALDEN

-

Nhlanhla Nene. Picture: BLOOMBERG/SIMON DAWSON

-

Planning Minister Trevor Manuel. Picture: SUNDAY TIMES

ANYONE wishing to counter the bleakness of Wednesday’s budget and feel wistful about the way things once were could start by reading the budget speech then finance minister Trevor Manuel delivered in February 2006.

The economy had grown 5% in 2005 and it was expected to continue growing at that pace for the foreseeable future. Commodity prices were reaching record highs, capital was flowing in, and SA was reaping the benefits of its tax-reform efforts and its success in bringing down debt levels and the cost of debt.

Mr Manuel could announce a R41bn revenue overrun and a budget deficit that had shrunk to 0.5% of gross domestic product (GDP), far below the 3.1% he had budgeted for just a year before. "The economic outlook is exceedingly favourable," Mr Manuel said in his inimitable way, as he upped spending, cut taxes — and proceeded to budget for a deficit of 1.5% for the next fiscal year (2006-07), falling to 1.2% in 2008-09.

In the event, even that proved to be too pessimistic, and 2006-07 turned out to be the first of two halcyon years in which SA ran a budget surplus but continued to boost spending, especially social spending, in real terms and to grant some generous tax concessions.

In retrospect, the budget surplus should have been much larger. Treasury officials at the time estimated that SA should have been running a surplus of 6% or more, reflecting cyclical (as opposed to structural) revenues of 6%-8%. That the revenue overruns were indeed purely cyclical and not more durable structural increases proved to be the case when the economy went into recession in 2008-09 and the deficit ballooned to that 6%-8% range.

There has been much debate about just how much of SA’s growth dividend at the time was thanks to its own efforts in opening up the economy and pursuing sound macroeconomic policies, and a good deal of it clearly was.

But, in retrospect, it is clear that the rising global tide over that period lifted all boats and SA sailed along with it.

Budgeting in the good times is in many ways more difficult that it is when times are tough, because when the money is rolling in everyone wants their share and it is very difficult for a finance minister to say no, especially a finance minister in a developing democracy such as SA, with its pressing social and economic needs.

So while it may be easy with hindsight to argue that Mr Manuel and his team should have budgeted for larger surpluses, at the time it was a huge stretch politically to make the case even for small surpluses.

In his February 2007 budget speech, Mr Manuel hailed SA’s economic good fortune, which was projected to continue with the commodity price rally continuing and economic growth expected to average just more than 5% a year over the following three years. Revenue for the 2006-07 fiscal year had come in R29bn over budget, so the outcome for the year was a R5bn surplus rather than the projected deficit.

This time, Mr Manuel budgeted for a fiscal surplus — of 0.6% of GDP for 2007-08, which came out at 1% in the end, thanks in part to yet another revenue overrun, of R15bn.

By the time of his budget speech in early 2008, the global storm clouds were just starting to gather, and he did warn that the course ahead would be somewhat tougher.

But the fiscal stance SA had adopted would help it weather the global storm, he said, and the budget he tabled not only pencilled in a 1% surplus for the 2008-09 fiscal year, but saw the surpluses continuing, at about 0.7% a year, over the following three years — all while the government continued to grow spending by 6% in real, inflation-adjusted terms.

The government debt ratio was projected to fall to just 16% of GDP by 2011. We can but wish that it had. For when Mr Manuel came to table what turned out to be his last budget speech, not long before the 2009 elections, he had to announce: "The storm that we spoke of last year has broken and it is more severe than anyone anticipated."

Presciently, he commented, too, "In a very short period, what started off as a financial crisis may become a second great depression."

It did not quite show in the numbers yet — SA’s economic growth rate had slowed to 3.1% for 2008 and the budget outcome was a small deficit, with revenue having fallen about R14bn short of budget.

But the public debt ratio had fallen to 23% of GDP, down from 48% in 1996, and though Mr Manuel warned against running up debt and imposing on future generations the burden of having to repay it with interest, he emphasised that SA was able to run a countercyclical fiscal stimulus on the strength of the secure and sustainable fiscal policies it had put in place.

With the economy at that stage still expected to grow 1.2% in 2009, he budgeted for strong real spending growth and a budget deficit of 3.8%, which would fall to 1.9% by 2011-12, when growth was expected to pick up again to the 4% range.

Pity Finance Minister Pravin Gordhan, who never again had it that good. Based on his 2009 and December 2015 record, Mr Gordhan seems to be the guy who is appointed finance minister only when there is real trouble in the economy. In 2009 the economy was headed into recession by the time President Jacob Zuma put him in place to deal with the crisis.

Fortunately, he inherited the fiscal space that had been created in the Manuel era, so SA could spend its way out of recession, which was fairly shallow in our case. Unfortunately, it’s clear with hindsight that the space he inherited was not nearly enough, nor did the government use it in the way it should have. As it turned out, the economy never did return to the 4% growth it had averaged between 2000 and 2008. For the past three years, it has not managed to hit even 2% and, as a Treasury presentation put it last year, "A structural deficit has now become entrenched."

While Mr Manuel had presided over a virtuous cycle in which the fiscal balances became better and better and the debt ratio and debt-servicing costs kept falling, Mr Gordhan’s first term as finance minister between 2009 and 2014 saw the public debt and its cost sharply rising.

It would be hard to find anyone who would argue that he was wrong to pursue a countercyclical fiscal policy stance that would support the economy and underpin living standards, especially for poor people, through the crisis. But a few things went wrong.

One was that the global economy never recovered from the crisis.

Advanced countries’ expansive monetary policies and continued strong growth in China meant that SA and other emerging markets did have a halcyon few post-crisis years in which capital flowed inwards in search of higher yields and commodity prices boomed, but by 2014 it was all coming apart and the turbulence in commodity and financial markets only became worse.

The second problem for SA was that while the global uptick between 2010 and 2013, along with the fiscal stimulus and the 2010 Soccer World Cup boost, may have given an illusion that the economy was not that bad, the underlying structural factors were becoming worse, with little in government economic policy to attract investment or enhance the economy’s longer-term growth potential. Once the commodities and capital booms ended, it was the proverbial case of the tide going out and SA’s economic growth nakedness being revealed.

That in turn related to a third problem, possibly the most significant one from a fiscal point of view, which was that we had largely the wrong kind of fiscal stimulus. Ideally, a government would run up the deficit and the debt level to help the economy through a temporary trough — but in a way that would help it to enhance its growth potential more permanently for future years.

Investing in infrastructure and in skills would be a major way to do that, and the argument for deficit spending at the time SA went into the crisis was that the government would spend to cushion the poor, as well as to support the expansion of SA’s growth potential, making capital spending a priority, with about R800bn in infrastructure investment on the drawing board. That did not happen.

Instead, too much of the spending increase went on the public sector payroll, thanks initially to pay increases granted at the height of the crisis in 2009-10 that were above inflation and more than the Treasury had agreed, as well as strong growth in the number of public servants.

In the five years to 2011, the size of the public sector payroll doubled, to take up almost 40% of noninterest spending.

In his 2010 budget speech, Mr Gordhan announced revenue had fallen R69bn short of budget estimates, with the economy shrinking 1.8% during 2009. The budget balance, he pointed out, had gone from a 1% surplus to a 7.3% deficit in just two years. But that had cushioned the economy against a larger decline in output and jobs, and had ensured that the government could maintain spending on social and economic services despite the decline in revenue.

With growth expected to pick up as the world recovered from recession, Mr Gordhan pencilled in slower but still significant real growth of 2% in government spending and higher borrowing in what he said was a temporary solution. The public debt ratio was seen blowing out to 40% by 2013 before stabilising last year.

It was not looking too bad by the time of his 2011 budget speech. Economic growth had picked up to 2.8% in 2010 and tax revenue had once again come in about 12% above budget. The original budget deficit estimate of 6.2% was revised to a less steep 5.3%, and the budget framework envisaged this falling to 4.8% and 3.8% in the following two years, with economic growth seen picking up to more than 4% in 2012 and 2013.

To his credit, Mr Gordhan had managed to extract about R30bn of savings from government departments. He used the budget speech to announce new measures to curb irregularities in public procurement and to prevent corruption.

There were concerns, however, about the growing level of government debt, which was heading towards a projected R1.3-trillion by 2013-14 — more than double the level at the end of 2008-09 — with debt costs now the fastest rising budget item. Mr Gordhan announced that guidelines had been proposed on long-term fiscal sustainability and debt management. He also expressed concern about the effect of the 2010 public sector pay settlement and the rapid rise in the public sector salary bill, which had doubled over five years.

There was much in his 2010 and 2011 budget speeches about the government’s commitment to a new growth path and a higher economic growth rate. By the time of the 2012 budget, the third of the Zuma administration, SA’s growth story was still seen as being on the rise, despite a global environment that Mr Gordhan described as "hugely uncertain", with the economy having grown 3% a year on average since 2009 — even though the 2012 growth rate was expected to fall to 2.7% before recovering.

"SA’s finances are in good health," Mr Gordhan told Parliament. Tax revenues had recovered since the crisis and the deficit was budgeted at 4.6% of GDP for 2012-13 but was planned to return to 3% in 2014-15, with the public debt ratio stabilising at about 38% of GDP.

It was in that budget that Mr Gordhan introduced an expenditure ceiling, which would cap government spending in nominal terms over three years — but the move did not receive a lot of emphasis in the speech, and attracted hardly any notice at the time.

It gained a higher profile the next year, with the extent of the fiscal challenge and SA’s growth challenge becoming ever more evident. "SA’s economic outlook is improving but requires that we actively pursue a different trajectory if we are to address the challenges ahead," Mr Gordhan said in his 2013 budget speech, which had the promise of the National Development Plan (NDP), which the Cabinet had approved. The speech had the NDP as its point of departure, Mr Gordhan emphasised.

With growth of only 2.5% in 2012, the budget deficit had come out rather higher than anticipated, at 5.2% for 2012-13, and was seen falling to 3.1% in 2015-16, but growth prospects had weakened over the next three years, Mr Gordhan said.

Real growth in government spending had been trimmed back to 2.3%. And there was a strong emphasis again on getting value for the money government spends and curbing corruption, but by now Mr Gordhan was becoming more despondent, it seemed, about how endemic it had become. Speaking of efforts to get value for money, he said, "Let me be frank. This is a difficult task, with too many points of resistance."

His 2014 budget speech, Mr Gordhan’s last before Mr Zuma unexpectedly replaced him with Nhlanhla Nene after the elections, was an even more sober affair. Mr Gordhan used the speech to recount what had been achieved since the crisis, with government spending having doubled in real terms over the past decade, and 57% of the budget now going on the "social wage". The government had borrowed R1-trillion over the past five years, he noted, as he again pushed the targets for stabilising the debt ratio outwards and upwards, with net debt now expected to stabilise at 45% only in 2016-17.

But he was still relatively optimistic about economic growth, which was projected to increase from 2.7% to 3.5% this year. We wish. Now we know the economy will not get close to even 1% this year. And by the time Mr Nene presented his first — and, as it turned out, his only — February budget speech last year, there was no getting away from the fact that growth estimates had consistently been undershot and debt stabilisation targets overshot.

Presenting his February budget speech a year ago, a realistic Mr Nene came straight to the point: "Today’s budget is constrained by the need to consolidate our public finances in the context of slower growth and rising debt."

It was, arguably, too little too late to prevent the rating agencies gearing up to downgrade. And Mr Nene’s abrupt firing by Mr Zuma in December did nothing to improve SA’s already damaged fiscal credibility.

News, views and analysis of Finance Minister Pravin Gordhan's 2016 budget

News, views and analysis of Finance Minister Pravin Gordhan's 2016 budget

Change: 0.83%

Change: 0.93%

Change: 0.95%

Change: 0.73%

Change: 1.91%

Data supplied by Profile Data

Change: 0.58%

Change: 0.43%

Change: 0.83%

Change: 0.00%

Change: 0.56%

Data supplied by Profile Data

Change: 0.18%

Change: 0.04%

Change: 0.11%

Change: -0.07%

Change: -0.12%

Data supplied by Profile Data

Change: -0.06%

Change: 0.51%

Change: 0.26%

Change: 0.34%

Change: 0.99%

Data supplied by Profile Data