THE life of a black person in SA is contaminated with a nervous condition. This is true for all black people at the University of Cape Town (UCT) — from a high-profile and prolific professor to a first-year student who is accepted to study, but is on a waiting list for accommodation and financial aid.

The condition drives me and many others to either go mad or commit suicide.

Much has been written in SA’s political and academic arenas about the event of March 9 2015. That day, I threw poo on the statue of Cecil John Rhodes on the UCT campus. That catalytic act was a political protest whose possible effect I understood very well. What I did not anticipate were the events that, as a consequence of our action, unfolded at UCT and other local universities as well as those abroad including Oxford University.

The event was part of the well-established history of resistance and political protest by black people that goes back to 1600. It was political, and informed by Black Consciousness philosophy.

When I formally registered at last at UCT in February 2011, I was aware of the institutional culture of the university from the point of view of an outsider who had some perspective from the inside. I had worked as a third-party unpaid researcher in the sociology department.

The department registered me so I could borrow library books and use its internet. In this third-party arrangement, I followed in the footsteps of Nat Nakasa, the prolific journalist for Drum magazine under apartheid. Nakasa was a third-party associate with the University of the Witwatersrand, while he worked as a journalist in Johannesburg.

This position introduced me rather rudely to the lived realities of being black in the white world. I went through the agonies of being black at UCT during the public lectures and public seminars, all of which seemed to be about the lived black realities in South Africa and around the world: and yet all these public lectures and symposiums were presented by white old men and women.

I realised there was something wrong about UCT, but I did not know what it was. When I finally registered at UCT, I made it my goal to search for and articulate it.

The first experience that reminded me of my previous black realities in public lectures and symposiums came during my first lectures for registered students in February 2011. I realised the problem at UCT was that most registered students in my political science lectures were white. Most, if not all, of my lecturers in political science were white, and my political studies department was full of white lecturers and professors. I asked many people about these lived realities and no one seemed to know why things were the way they were.

They still continue to be so. And no one seemed to be keen to discuss the matters of race and racism at UCT.

...

DURING my time at UCT, a lot has taken place in relation to the political debates of racial exclusion of black students, either on financial grounds, or on academic grounds. In September 2010, I took part in an admissions policy debate at the university. UCT decided that year to use race as a proxy for admission of students. Many people in and outside the academy criticised the university’s decision. Four years later, the institution backtracked.

In October 2014, UCT vice-chancellor Max Price called a public symposium on Transformation in Higher Education in SA, with a particular focus on UCT. Other university leaders, such as Prof Jonathan Jansen and Prof Mamokgethi Phakeng, were on the panel. During this talk, I realised something needed to be done, and that there was no form of meaningful debate in lecture halls and symposium rooms that would ever change the status quo at UCT without a radical and revolutionary act that would criticise the university and call to account its institutional racism.

Before the October transformation debate, few people had spoken or written critically about the institutional racism at UCT, notwithstanding that they were part of the institution. One person who did speak out was the newly arrived Prof Xolela Mangcu, who wrote as part of his first articles at the university, that the problem at UCT was its council, the highest decision-making body, which was full of white old men.

Mangcu said the senate, the second-highest decision-making body that is exclusively formed of full professors, was equally a problem. This meant that UCT was — and is — full of old white professors.

By the end of 2014, I was clear about the problem and what needed to be done about it. However, I did not know what I needed to target as the symbol that represented the institutional racism at UCT, let alone the personal racism. Just before the end of 2014, I attended a symposium at UCT that was addressed by Dr Shose Kessi, one of the prominent and vocal black scholars at UCT today.

She spoke about research she was conducting with students from her psychology department. At that symposium, Price was asked when the statue of Rhodes would be removed from campus. Price said he was not there as a panellist and the topic under discussion was not the statues.

After the symposium, Wandile Kasibe, Baxolele Zono, Zabelo Mcinzima and I discussed how frustrated we all were that Price had refused to answer the question. We discussed doing something about the statue, and talked about whether it ought to be brought down violently as a form of political protest.

Kasibe said, "The statue is the right target of protest. However, the way in which you remove the statue is what will count. The last thing you want is to be seen to be involved in an act of criminality."

KASIBE’s reasoning alerted us to the possibility of being seen as criminals, and thus endangering our individual and collective opportunity of being students.

In Kasibe’s case, he risked both his job as an employee of the Iziko South African Museum and as a strong future doctoral candidate at UCT. He was enrolled to start this in a few months.

Kasibe said we needed to engage in a psychological fight with the white liberals that were keeping Rhodes as the face of the university. He said we had to leave the pain of the psychological effect lingering in the minds and souls of white liberals. We decided to consult trusted black lawyers for advice. I did not hear from Sabelo or Baxolele for a while. The lived reality of our nervous conditions always relates back to our lived realities as black people.

Baxolele was due to hand in his master’s thesis soon, and Sabelo was about to start his new job.

Kasibe was busy with his work, and I had just finished one more precious year of study. The state of our nervous conditions has imprisoned us all, like any other black person in SA. From a full-time black academic to a first-year black student, our nervous condition is the same. We are fearful of what will happen to us while we are in the white world, that if we too disrupt white power radically, we will find ourselves in the wilderness of a cold white world like Zimbabwean novelist and poet, Dambudzo Marechera.

I spent the whole of December 2014 thinking about the statue as a symbol of white power at UCT. And I thought about how it could be removed from campus.

I met Kasibe again to discuss the plan of action, focusing on more concrete action, with a time and date as well as what exactly would be done. He suggested that we use human excrement that runs exposed through Khayelitsha so that we could speak to the urgent need for human dignity for the black people living in shacks in Khayelitsha in inhumane conditions and indignity. Kasibe said that, by throwing poo at the statue of Rhodes, we would symbolise the filthy way in which Rhodes mistreated our people in the past. Equally, we would show disgust at the manner in which UCT, as a leading South African institution of learning, celebrates the genocidal Rhodes. In short, the poo would be an institutional appraisal of UCT.

WHAT was left to do was to decide who would do the act, how the act would be done, for how long, and at what time. By January last year, I was already thinking about the consequences of the political protest. My ideas were informed by courage, and yet fear was part of them almost simultaneously.

The fear was informed by the possibility that the university would take disciplinary action against me. By the end of January, I was already thinking about the ways and means of making the political art less punishable in the event that I got caught. I knew the act would have to take place at the beginning of the year, when everyone was back on campus. By February, I had decided that I would be using poo as the tool of my political protest. I was thinking about the logistics, the date and timing of the event.

As the fear kicked in, I had to identify exactly what caused it. I realised it was because of my nervous condition due to my existence in the white world.

I feared that if I acted without being registered as a student for that academic year, I might lose my financial aid. Thus, I had to wait until I was registered and had received financial aid. After I had fulfilled all the necessary requirements for being a student, I was confronted with the reality of the character that the protest would take. I struggled with the fear of what I would say I was doing with the statue if I was caught.

While experiencing this dread, I discovered that the annual Infecting the City live art performance festival at which artists perform their art work in and around Cape Town, was scheduled to take place in March.

The opening date of Infecting the City was to be on March 9 2015. I decided this was the right date for my own protest performance. I decided that I would do it in the morning.

On the night of March, 8 I asked my friend, the artist Dathini Mzayiya, to make placards for my political performance. I had decided that if I was caught, I would say I was participating in the Infecting the City art project organised by an institute associated with UCT. I would say that, as an artist, I did not need to be on the formal list of performing artists to produce art works that speak directly to the university’s challenges of racism. With this sound justification, my fear evaporated. My placards were to read, "Exhibit White Arrogance @ UCT" and "Exhibit Black Assimilation @ UCT".

I borrowed a drum from one of the very few black lecturers at UCT’s music school. I had my pink makarapa (hard hat) and a whistle. I decided to perform topless in running tights and running shoes. This had to be a true performance.

On March 9, I took a cab to Khayelitsha. Close to Mew Way Hall, I got out of the car and took portable containers with poo inside them obtained the night before, and put them inside the car boot.

We drove to UCT, stopping on the way to collect the placards.

While I was in Woodstock, at Mzayiya’s studio, I phoned the Cape Times and e.tv to inform them about the performance.

The cab driver dropped me at UCT’s upper campus. I asked a group of students gathered round the statue with their lecturer to move aside, as a political protest was about to start. They did so readily.

I put safety tape around the statue. And then I started to throw the poo on the statue, simultaneously blowing the whistle and beating the drum.

Campus security arrived and asked what was happening. I told them it was performance art, and they let me continue.

Suddenly, the Cape Times and e.tv were there, and people started gathering around, asking questions about the political art.

It was a performance that was to last the whole day. By midday, other black students had joined me and there, on that day, March 9, 2015, the #RhodesMustFall student movement was born out of pain and frustration — what we later called Black Pain.

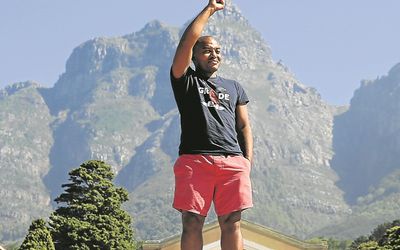

• Maxwele is a political activist, and a registered student at UCT

Change: 0.26%

Change: 0.41%

Change: 0.74%

Change: 0.41%

Change: -0.46%

Data supplied by Profile Data

Change: -0.01%

Change: 0.90%

Change: 0.26%

Change: 0.00%

Change: 0.66%

Data supplied by Profile Data

Change: 0.82%

Change: 0.68%

Change: 0.64%

Change: 1.03%

Change: 0.82%

Data supplied by Profile Data

Change: 0.17%

Change: -0.31%

Change: 0.94%

Change: 0.17%

Change: -0.05%

Data supplied by Profile Data