EGYPTIAN scholar-diplomat Boutros Boutros-Ghali, who died at the age of 93 last month, served as the first African and first Arab United Nations (UN) secretary-general between 1992 and 1996.

He was steeped in the intricacies of Third World diplomacy, having served as Egypt’s minister of state for foreign affairs between 1977 and 1991. He had a profound and intuitive grasp of the global South and was deeply involved in both the Arab-Israeli dispute and the politics of the Organisation of African Unity.

Having obtained a doctorate in international law from the Sorbonne in Paris and taught at Cairo University for 28 years, Boutros-Ghali was the most intellectually accomplished secretary-general in the history of the post.

The scion of a Coptic Christian family, his assassinated grandfather had served as Egypt’s prime minister, while his father served as finance minister. Boutros-Ghali was aloof, and UN staff referred to him as "the pharaoh" due to his authoritarian leadership style. He did not endear himself to them when he noted that the only way to run a bureaucracy was "by stealth and sudden violence".

He broke with tradition by failing to attend the informal meetings of the powerful 15-member UN Security Council, which he found tedious.

The introverted, workaholic Boutros-Ghali sought to play the role of "the pope on the East River". He bluntly condemned the double standards of Western powers in selectively authorising UN interventions in "rich men’s wars" in the Balkans, while ignoring Africa’s "orphan conflicts".

During his tenure in office, the Egyptian displayed a fierce and often courageous independence: he insisted on maintaining a veto over airstrikes in Bosnia; he refused Washington’s demand to approve a UN deployment in Haiti until troop contributors and time frames had been agreed; he consistently complained about the undemocratic nature of the UN Security Council; chastised his political masters for manipulating the UN over Iraq and Libya; and berated them for dumping impossible tasks on the world body without providing it with the resources to do the job.

All of this was recorded in a bitter 1999 memoir, Unvanquished.

Boutros-Ghali also criticised Washington relentlessly for refusing to pay its $1.3bn debt to the UN, while domineeringly seeking to set its agenda.

Nativist US politicians eventually turned on him, erroneously blaming Boutros-Ghali for everything from the death of US soldiers in Somalia to the failure to protect "safe havens" in Bosnia and obstruction of the reform of the UN bureaucracy.

The Egyptian complained prophetically that he felt like a man condemned to execution. His nemesis, US ambassador to the UN, Madeleine Albright, whom he deemed a diplomatic novice, would eventually act as former president Bill Clinton’s willing executioner in vetoing his re-election in 1996.

Although he focused much of his venom on the US, the Egyptian often failed to criticise some of the shortcomings of other powerful members of the UN. For example, he was often soft on France, the closest ally of this Sorbonne-educated intellectual, who headed La Francophonie after 1996.

Despite a discredited Gallic role in the 1994 Rwandan genocide, Boutros-Ghali supported France’s controversial military intervention in the country.

Like the Shakespearean Iago’s hatred of the black Othello, the venom of the attacks on Boutros-Ghali by his western critics was often irrational. He complained that the British media was unhappy with him over the Bosnian crisis "because I am a wog". He often expressed the southern criticism that the rich North was too focused on security issues to the detriment of socioeconomic development. He frequently decried the lack of democratisation in the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund.

Boutros-Ghali’s enduring legacy to the UN will be An Agenda for Peace, a landmark document published in 1992 on the tools and techniques of peacemaking, peacekeeping, and peacebuilding for a post-Cold War era that still remains an indispensable guide for conflict management efforts.

His tenure as UN secretary-general also witnessed peacekeeping successes in Cambodia, El Salvador and Mozambique. Contrary to claims by his critics, he cut the UN bureaucracy from 12,000 to 9,000 while freezing the budget, saving $100m a year.

However, for all his undoubted achievements, the pompous pharaoh eventually earned himself the unenviable distinction of being the only UN secretary-general to have been denied a second term in office.

• Dr Adebajo is executive director of the Centre for Conflict Resolution in Cape Town, and visiting professor at the University of Johannesburg

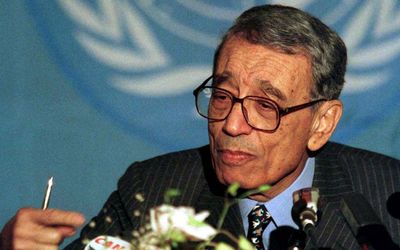

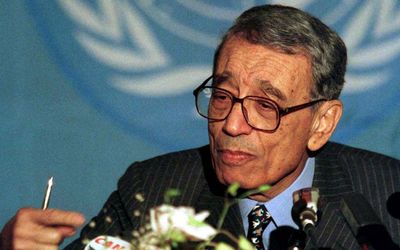

Boutros Boutros-Ghali. Picture: REUTERS/PAULO COCCO

EGYPTIAN scholar-diplomat Boutros Boutros-Ghali, who died at the age of 93 last month, served as the first African and first Arab United Nations (UN) secretary-general between 1992 and 1996.

He was steeped in the intricacies of Third World diplomacy, having served as Egypt’s minister of state for foreign affairs between 1977 and 1991. He had a profound and intuitive grasp of the global South and was deeply involved in both the Arab-Israeli dispute and the politics of the Organisation of African Unity.

Having obtained a doctorate in international law from the Sorbonne in Paris and taught at Cairo University for 28 years, Boutros-Ghali was the most intellectually accomplished secretary-general in the history of the post.

The scion of a Coptic Christian family, his assassinated grandfather had served as Egypt’s prime minister, while his father served as finance minister. Boutros-Ghali was aloof, and UN staff referred to him as "the pharaoh" due to his authoritarian leadership style. He did not endear himself to them when he noted that the only way to run a bureaucracy was "by stealth and sudden violence".

He broke with tradition by failing to attend the informal meetings of the powerful 15-member UN Security Council, which he found tedious.

The introverted, workaholic Boutros-Ghali sought to play the role of "the pope on the East River". He bluntly condemned the double standards of Western powers in selectively authorising UN interventions in "rich men’s wars" in the Balkans, while ignoring Africa’s "orphan conflicts".

During his tenure in office, the Egyptian displayed a fierce and often courageous independence: he insisted on maintaining a veto over airstrikes in Bosnia; he refused Washington’s demand to approve a UN deployment in Haiti until troop contributors and time frames had been agreed; he consistently complained about the undemocratic nature of the UN Security Council; chastised his political masters for manipulating the UN over Iraq and Libya; and berated them for dumping impossible tasks on the world body without providing it with the resources to do the job.

All of this was recorded in a bitter 1999 memoir, Unvanquished.

Boutros-Ghali also criticised Washington relentlessly for refusing to pay its $1.3bn debt to the UN, while domineeringly seeking to set its agenda.

Nativist US politicians eventually turned on him, erroneously blaming Boutros-Ghali for everything from the death of US soldiers in Somalia to the failure to protect "safe havens" in Bosnia and obstruction of the reform of the UN bureaucracy.

The Egyptian complained prophetically that he felt like a man condemned to execution. His nemesis, US ambassador to the UN, Madeleine Albright, whom he deemed a diplomatic novice, would eventually act as former president Bill Clinton’s willing executioner in vetoing his re-election in 1996.

Although he focused much of his venom on the US, the Egyptian often failed to criticise some of the shortcomings of other powerful members of the UN. For example, he was often soft on France, the closest ally of this Sorbonne-educated intellectual, who headed La Francophonie after 1996.

Despite a discredited Gallic role in the 1994 Rwandan genocide, Boutros-Ghali supported France’s controversial military intervention in the country.

Like the Shakespearean Iago’s hatred of the black Othello, the venom of the attacks on Boutros-Ghali by his western critics was often irrational. He complained that the British media was unhappy with him over the Bosnian crisis "because I am a wog". He often expressed the southern criticism that the rich North was too focused on security issues to the detriment of socioeconomic development. He frequently decried the lack of democratisation in the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund.

Boutros-Ghali’s enduring legacy to the UN will be An Agenda for Peace, a landmark document published in 1992 on the tools and techniques of peacemaking, peacekeeping, and peacebuilding for a post-Cold War era that still remains an indispensable guide for conflict management efforts.

His tenure as UN secretary-general also witnessed peacekeeping successes in Cambodia, El Salvador and Mozambique. Contrary to claims by his critics, he cut the UN bureaucracy from 12,000 to 9,000 while freezing the budget, saving $100m a year.

However, for all his undoubted achievements, the pompous pharaoh eventually earned himself the unenviable distinction of being the only UN secretary-general to have been denied a second term in office.

• Dr Adebajo is executive director of the Centre for Conflict Resolution in Cape Town, and visiting professor at the University of Johannesburg

Change: -0.04%

Change: 0.05%

Change: -0.02%

Change: 0.44%

Change: -1.58%

Data supplied by Profile Data

Change: -1.00%

Change: 0.40%

Change: -0.04%

Change: 0.00%

Change: 0.09%

Data supplied by Profile Data

Change: 1.23%

Change: 0.93%

Change: 1.16%

Change: 1.79%

Change: 0.69%

Data supplied by Profile Data

Change: 0.48%

Change: 0.20%

Change: -0.26%

Change: -1.91%

Change: -0.37%

Data supplied by Profile Data