THE June consumer price inflation rate of 4.7% released last week proved the market wrong by an unusually large margin — the consensus forecast had been 5%.

That did not persuade the Reserve Bank’s monetary policy committee to hold back on hiking interest rates, as some had hoped. Nor should it have — the committee must look forward, not backward, and the new figure would not even have been incorporated in its forecast by the time it made its decision on Thursday.

However, the new inflation number prompted the committee to pen a carefully argued statement to explain its "finely balanced" decision to lift the benchmark repo rate by 25 basis points to 6% — a level last seen in late 2010.

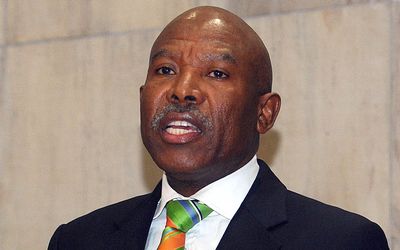

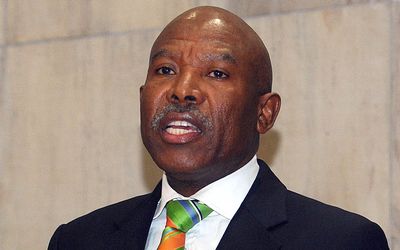

The committee directly countered the notion that the latest inflation number made any material difference. It said the respite was expected to be temporary and Reserve Bank governor Lesetja Kganyago pointed out, too, that June’s figure was still higher than May’s 4.6%.

And the medium-term outlook is the committee’s concern, with inflation expected to breach the top of the target range for the first two quarters of next year, and "upside risk" to the forecast from electricity prices and the rand exchange rate in particular.

However, the committee also made a point of responding to the critics on the argument that hiking interest rates is the wrong tool to use when the drivers of inflation are from the supply side rather than the demand side — what economists call "cost push" rather than "demand pull".

Several economists have raised this issue lately. The argument would be that higher interest rates can curb inflation only through the effect they have in reducing demand and hence the pricing power of retailers and others.

If demand is not the problem — and in an economy as weak as SA’s, with consumer confidence so low it doesn’t seem to be — then raising the repo rate would be the wrong way to go. It would further damp consumer confidence and spending without a discernible effect on inflation.

In SA’s case, the pressure on prices is coming from factors such as administered prices (especially electricity), food prices and the weak exchange rate and, so the argument goes, monetary policy makers can’t affect any of that.

The committee last week took on that argument explicitly. It said it was cognisant of the fact that domestic inflation was not driven by demand factors, and that household spending was subdued, as was the economy.

However, it emphasised, firstly, that it was wary of "second-round effects" — of the risk; in other words, that businesses, trade unions and other price setters will react to all these higher costs by upping their own prices, so setting inflation spiralling. Secondly, the committee expressed its concern that if it did not act against inflationary pressures — from wherever they come — that would "cause inflation expectations to become entrenched at higher levels".

As it is, the second quarter inflation expectations survey — which is new since the committee last met in May — shows a deterioration in inflation expectations, especially those of business people.

The committee reminded us that one of the most important tools in an inflation targeting the central bank’s toolkit is its ability to manage expectations and so influence behaviour.

The Bank last week did just that, making it clear that it would act, as it has said for months that it would, to combat an inflation rate that is climbing to the top of the target range.

It has flagged the risk that inflation could climb even faster if the exchange rate crashes — and last week’s events in the commodities and currency markets seem to heighten that risk. And that’s even before the US Federal Reserve starts to hike rates, posing another risk to currencies such as the rand.

That suggests even if the view through the rearview mirror isn’t so bad, the view ahead could get a lot worse — and the committee’s choice was the right one.

South African Reserve Bank governor Lesetja Kganyago announces the decision on interest rates in Pretoria on Thursday. Picture: PUXLEY MAKGATHO

THE June consumer price inflation rate of 4.7% released last week proved the market wrong by an unusually large margin — the consensus forecast had been 5%.

That did not persuade the Reserve Bank’s monetary policy committee to hold back on hiking interest rates, as some had hoped. Nor should it have — the committee must look forward, not backward, and the new figure would not even have been incorporated in its forecast by the time it made its decision on Thursday.

However, the new inflation number prompted the committee to pen a carefully argued statement to explain its "finely balanced" decision to lift the benchmark repo rate by 25 basis points to 6% — a level last seen in late 2010.

The committee directly countered the notion that the latest inflation number made any material difference. It said the respite was expected to be temporary and Reserve Bank governor Lesetja Kganyago pointed out, too, that June’s figure was still higher than May’s 4.6%.

And the medium-term outlook is the committee’s concern, with inflation expected to breach the top of the target range for the first two quarters of next year, and "upside risk" to the forecast from electricity prices and the rand exchange rate in particular.

However, the committee also made a point of responding to the critics on the argument that hiking interest rates is the wrong tool to use when the drivers of inflation are from the supply side rather than the demand side — what economists call "cost push" rather than "demand pull".

Several economists have raised this issue lately. The argument would be that higher interest rates can curb inflation only through the effect they have in reducing demand and hence the pricing power of retailers and others.

If demand is not the problem — and in an economy as weak as SA’s, with consumer confidence so low it doesn’t seem to be — then raising the repo rate would be the wrong way to go. It would further damp consumer confidence and spending without a discernible effect on inflation.

In SA’s case, the pressure on prices is coming from factors such as administered prices (especially electricity), food prices and the weak exchange rate and, so the argument goes, monetary policy makers can’t affect any of that.

The committee last week took on that argument explicitly. It said it was cognisant of the fact that domestic inflation was not driven by demand factors, and that household spending was subdued, as was the economy.

However, it emphasised, firstly, that it was wary of "second-round effects" — of the risk; in other words, that businesses, trade unions and other price setters will react to all these higher costs by upping their own prices, so setting inflation spiralling. Secondly, the committee expressed its concern that if it did not act against inflationary pressures — from wherever they come — that would "cause inflation expectations to become entrenched at higher levels".

As it is, the second quarter inflation expectations survey — which is new since the committee last met in May — shows a deterioration in inflation expectations, especially those of business people.

The committee reminded us that one of the most important tools in an inflation targeting the central bank’s toolkit is its ability to manage expectations and so influence behaviour.

The Bank last week did just that, making it clear that it would act, as it has said for months that it would, to combat an inflation rate that is climbing to the top of the target range.

It has flagged the risk that inflation could climb even faster if the exchange rate crashes — and last week’s events in the commodities and currency markets seem to heighten that risk. And that’s even before the US Federal Reserve starts to hike rates, posing another risk to currencies such as the rand.

That suggests even if the view through the rearview mirror isn’t so bad, the view ahead could get a lot worse — and the committee’s choice was the right one.

Post a comment