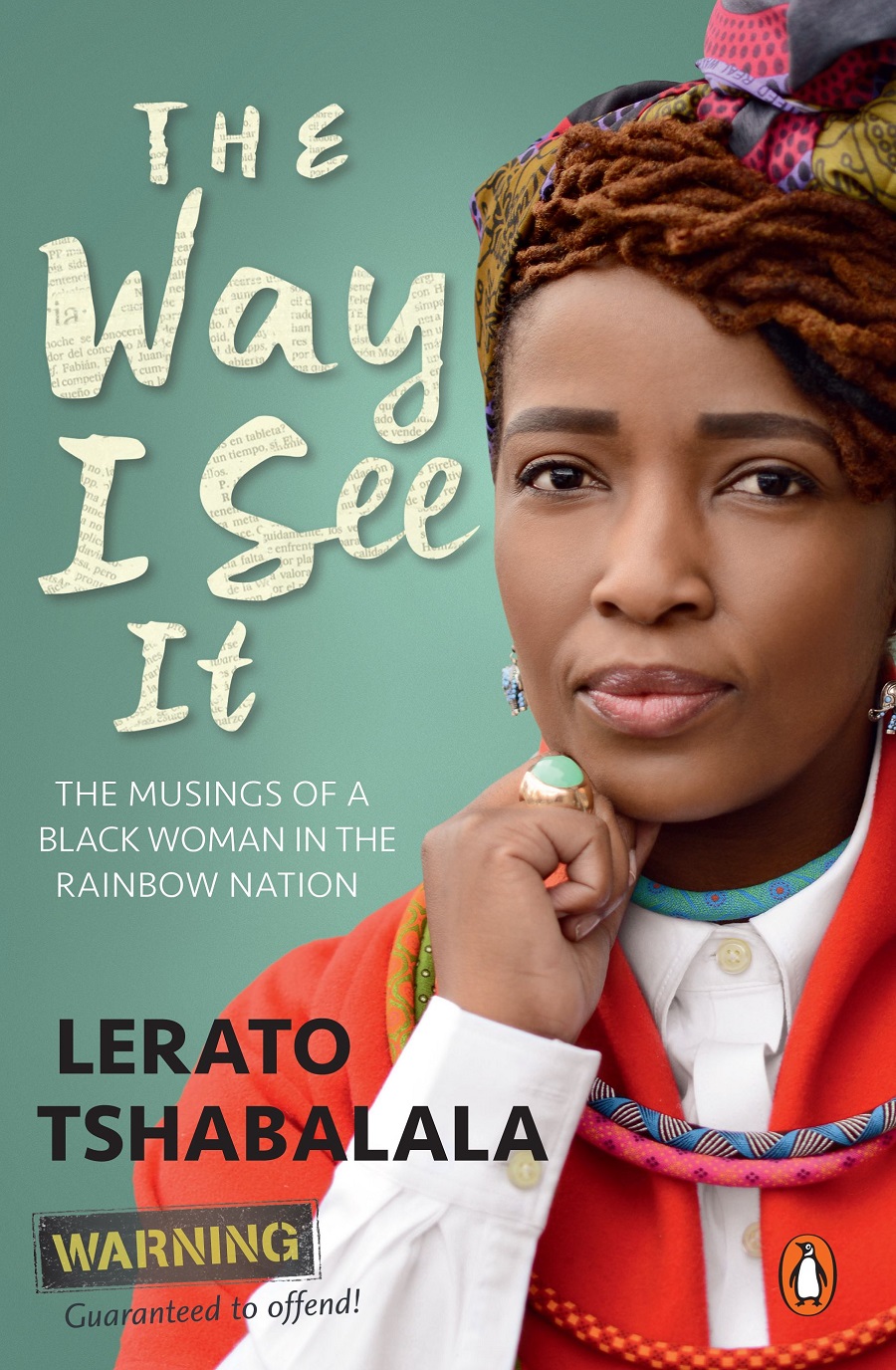

BOOK REVIEW: The Way I See it: Musings Of A Black Woman In the Rainbow Nation

by Lungile Sojini

2016-08-19 06:01:51.0

WRITING about race relations is a tricky challenge. More so when you take sides — and are seen as depicting one race as more desirable than others in certain aspects.

Former magazine editor Lerato Tshabalala must have wrestled with this dilemma as she penned her controversial new book, The Way I See It: Musings of a Black Woman in the Rainbow Nation. But she went ahead, risking making enemies.

Her publisher, Penguin Random House, has come in for a beating, being accused of publishing material that conforms to white people’s unpleasant view of black people. Not that Tshabalala hasn’t written about all SA’s races, nor angered her own.

One chapter that has not gone down well with her racial peers deals with the poor service Tshabalala has had from black providers. So she "switched races" and brands black providers as unprofessional, uncommitted, and unworthy of her business.

Several people have argued the book is fuelled by Tshabalala’s own self-hate.

The problem, obviously, is painting an entire race with the same brush. Black people often joke among themselves about their (generalised) shortcomings, such as adhering to "African time" — the notion that black people are relaxed in their attitudes towards punctuality. But this makes white people seem beyond reproach on this issue, when, naturally, not all are.

Even so, Tshabalala has written a lighthearted take on many contemporary social issues. She tackles politics, friendship and dating, beauty, sex, and tenders.

She’s outspoken about the things that rile her, and her language is peppered with her favourite expletives. "I’m going to curse/swear in this book," she warns in the preface.

In a chapter titled "The top five reality checks for everydamnbody" (proving her vitriol is unbiased), she tears into the prejudices of blacks, whites, Indians, and coloureds.

None of this is preachy. It’s entertaining, but somewhat condescending, perhaps even patronising — Tshabalala tells blacks when to eat, Indians who to have as role models, whites who to have as friends, and coloureds how they ought to relate to other races.

Luckily for Tshabalala, there is a topic she is qualified to comment on: the media, particularly social media. Here she flourishes. She attempts to paint a picture of how social media has changed human behaviour, sometimes for the worse.

Nostalgia is a notable theme: how things used to be better, or simpler, in the past. This is Tshabalala at her best — at least where readers won’t desert her for her antiblack "self-hate".

Born in Soweto, Tshabalala attended Model C schools. Her career in journalism had a pinnacle in her editorship of True Love, one of the largest (in terms of readership) women’s magazines in SA. In 2013 the Mail & Guardian listed her as one of its 200 young people to watch in SA.

The book exposes a deadly feature of modern society: the need to be flattered. Unless the other parties dwell on our more positive sides, we are reluctant to launch ourselves into self-introspection, seems to be the viewpoint favoured by Tshabalala’s critics.

So, instead of regarding The Way I See It as antiblack, critics should look at it as a goad to see how far the black race (and every other race in the Rainbow Nation) can travel in terms of bettering its work ethic and professionalism.

Tshabalala’s wish must have been to criticise her targets, not alienate them, while delivering the truth the way she sees it, no matter how uncool. But her message risks being lost in the noise of dissenting voices.

As an attempt to win the hearts and respect of South Africans, The Way I See It makes for an explosive debut.

Picture: THINKSTOCK

WRITING about race relations is a tricky challenge. More so when you take sides — and are seen as depicting one race as more desirable than others in certain aspects.

Former magazine editor Lerato Tshabalala must have wrestled with this dilemma as she penned her controversial new book, The Way I See It: Musings of a Black Woman in the Rainbow Nation. But she went ahead, risking making enemies.

Her publisher, Penguin Random House, has come in for a beating, being accused of publishing material that conforms to white people’s unpleasant view of black people. Not that Tshabalala hasn’t written about all SA’s races, nor angered her own.

One chapter that has not gone down well with her racial peers deals with the poor service Tshabalala has had from black providers. So she "switched races" and brands black providers as unprofessional, uncommitted, and unworthy of her business.

Several people have argued the book is fuelled by Tshabalala’s own self-hate.

The problem, obviously, is painting an entire race with the same brush. Black people often joke among themselves about their (generalised) shortcomings, such as adhering to "African time" — the notion that black people are relaxed in their attitudes towards punctuality. But this makes white people seem beyond reproach on this issue, when, naturally, not all are.

Even so, Tshabalala has written a lighthearted take on many contemporary social issues. She tackles politics, friendship and dating, beauty, sex, and tenders.

She’s outspoken about the things that rile her, and her language is peppered with her favourite expletives. "I’m going to curse/swear in this book," she warns in the preface.

In a chapter titled "The top five reality checks for everydamnbody" (proving her vitriol is unbiased), she tears into the prejudices of blacks, whites, Indians, and coloureds.

None of this is preachy. It’s entertaining, but somewhat condescending, perhaps even patronising — Tshabalala tells blacks when to eat, Indians who to have as role models, whites who to have as friends, and coloureds how they ought to relate to other races.

Luckily for Tshabalala, there is a topic she is qualified to comment on: the media, particularly social media. Here she flourishes. She attempts to paint a picture of how social media has changed human behaviour, sometimes for the worse.

Nostalgia is a notable theme: how things used to be better, or simpler, in the past. This is Tshabalala at her best — at least where readers won’t desert her for her antiblack "self-hate".

Born in Soweto, Tshabalala attended Model C schools. Her career in journalism had a pinnacle in her editorship of True Love, one of the largest (in terms of readership) women’s magazines in SA. In 2013 the Mail & Guardian listed her as one of its 200 young people to watch in SA.

The book exposes a deadly feature of modern society: the need to be flattered. Unless the other parties dwell on our more positive sides, we are reluctant to launch ourselves into self-introspection, seems to be the viewpoint favoured by Tshabalala’s critics.

So, instead of regarding The Way I See It as antiblack, critics should look at it as a goad to see how far the black race (and every other race in the Rainbow Nation) can travel in terms of bettering its work ethic and professionalism.

Tshabalala’s wish must have been to criticise her targets, not alienate them, while delivering the truth the way she sees it, no matter how uncool. But her message risks being lost in the noise of dissenting voices.

As an attempt to win the hearts and respect of South Africans, The Way I See It makes for an explosive debut.