EVERY now and then the world throws up a maverick, someone ready to sacrifice health, love and personal happiness for a cause. Emily Hobhouse was one.

"Her message crosses decades," says Elsabé Brits, author of Emily Hobhouse: Beloved Traitor, the first full biography of the Englishwoman who is most famous for pointing out the appalling conditions in the British-run Anglo Boer War concentration camps.

"She didn’t come to SA to defend the Boer cause, she came with a message for all wars: it is always the women and children that suffer the most," Brits says.

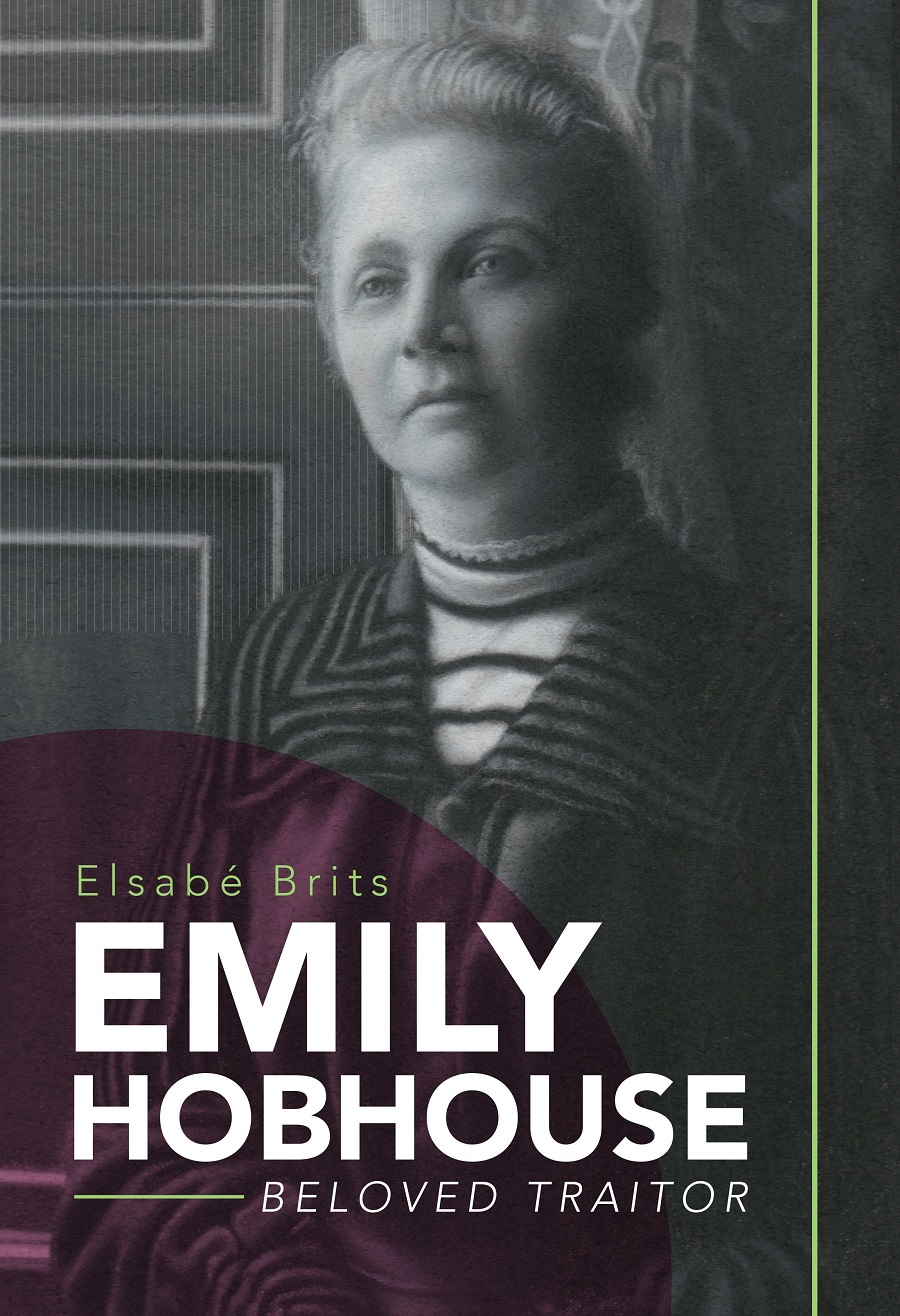

History, of course, has mostly been written by men, about men. Brits’s gorgeously illustrated book brings Hobhouse to life through a large quantity of photographs, some until now unpublished, copies of letters, telegrams, personal notes and even receipts for items such as oxen and ploughs.

Brits’s interest in Hobhouse was sparked in mid-2013 when she picked up a short biography of Hobhouse in a bric-a-brac shop in Prince Albert in the Karoo. "There was something about a ploughing scheme… She ploughed the whole of the Transvaal and the Free State and I thought, ‘There’s something more to this woman’."

In the aftermath of the Anglo-Boer War, the Afrikaners were reluctant to make use of the £3m in reparations money — Hobhouse argued there was a psychological barrier because of the effectiveness of Herbert Kitchener’s Scorched Earth policy in which anything that might be of use to the Boer forces in the field was destroyed, and the women and children moved to camps. In the end about 30,000 white people and 25,000 black people died in the camps, while 21,144 British soldiers and 7,894 Boer soldiers lost their lives.

Hobhouse campaigned for the rights of white and black equally.

...

BY THE time Hobhouse died in 1926 she was a lonely woman who had often been vilified for her humanitarian work in SA, and also in Germany during the First World War. She had narrowly missed being charged with treason for meeting with German officials during the First World War, and she yearned for acknowledgement. That she only got posthumously.

Hobhouse is still the only foreigner to have had a state funeral in SA, and she was made an honorary South African citizen for her humanitarian work here.

Pretty much everything was against Hobhouse, right from the start. Born in April 1860 to an upper middle-class British family, she was expected only to be a dutiful wife.

Yet, even as a 16-year-old, Hobhouse realised what mattered to her was unlike what mattered to others. She yearned to see humanity working in harmonious tandem, despite differences.

Not until she was 35 and her very conservative father dead was she able to start the work for which she became famous and notorious.

"What surprised me the most," Brits says, "is the wonderful endurance she had. There were times when she was hungry, when she couldn’t wash for five days. She had no significant other to confide in. She did write letters, but they took three to four weeks to get there, yet she didn’t at a point say, ‘Listen, I’ve had enough.’

"There are very few people in the world who are brave enough to do that (campaign, against popular sentiment, for the rights of the supposed enemy), and she did it again in another war."

Courage, as has often been pointed out, is not the absence of fear, it is carrying on despite fear. Hobhouse had courage in spades. She continued her battle despite the social mores of the time, personal depression, other health problems, and the opprobrium of friends, family, and compatriots.

Humanity needs people such as Hobhouse, prepared to walk their own path, determined to point out society’s flaws and work to fix them. They don’t come around often.

Hobhouse was often afraid, yet her concern for the underdog was always bigger than her personal needs. Starting with her teenage visits to people her father wanted ostracised, she went on to campaign for the rights of Boer women and children, and the rights of German women and children during the First World War, and worked for women’s suffrage.

Ironically, she missed out on being allowed to vote in the UK after the passing of legislation in 1918 granting the vote to women over 30 who were married, owned property, or were graduates.

...

DYING in 1926, Hobhouse wrote: "Little life remains in me, (and) I do feel some sort of reinstitution in the public mind of England and documentary evidence of it, would do more than anything else to brighten the remaining time. Few know what a heavy burden it has been to carry for quarter of a century."

"It’s a sad story," Brits says. "She was fiercely patriotic towards England… She has been misunderstood from so many sides, and by so many people. The last six letters she wrote I transcribed. They made me quite sad."

Sad it might be, but it is also a story of phenomenal courage. The truth is Hobhouse was remarkable, but there is another truth too — there are other unsung female heroes from yesteryear whose stories need to be told. Some crossed the Sahara at a time when few Europeans had done so; some developed mathematics we use today. Brits has been bitten by the bug. She foresees more on Hobhouse coming from her hand, and then perhaps something on one of these other female achievers.

• August is Women’s Month. August 19 is World Humanitarian Day

In Emily Hobhouse: Beloved Traitor, Elsabé Brits delves into the life of this courageous woman. Picture: LIZA VAN DEVENTER

EVERY now and then the world throws up a maverick, someone ready to sacrifice health, love and personal happiness for a cause. Emily Hobhouse was one.

"Her message crosses decades," says Elsabé Brits, author of Emily Hobhouse: Beloved Traitor, the first full biography of the Englishwoman who is most famous for pointing out the appalling conditions in the British-run Anglo Boer War concentration camps.

"She didn’t come to SA to defend the Boer cause, she came with a message for all wars: it is always the women and children that suffer the most," Brits says.

History, of course, has mostly been written by men, about men. Brits’s gorgeously illustrated book brings Hobhouse to life through a large quantity of photographs, some until now unpublished, copies of letters, telegrams, personal notes and even receipts for items such as oxen and ploughs.

Brits’s interest in Hobhouse was sparked in mid-2013 when she picked up a short biography of Hobhouse in a bric-a-brac shop in Prince Albert in the Karoo. "There was something about a ploughing scheme… She ploughed the whole of the Transvaal and the Free State and I thought, ‘There’s something more to this woman’."

In the aftermath of the Anglo-Boer War, the Afrikaners were reluctant to make use of the £3m in reparations money — Hobhouse argued there was a psychological barrier because of the effectiveness of Herbert Kitchener’s Scorched Earth policy in which anything that might be of use to the Boer forces in the field was destroyed, and the women and children moved to camps. In the end about 30,000 white people and 25,000 black people died in the camps, while 21,144 British soldiers and 7,894 Boer soldiers lost their lives.

Hobhouse campaigned for the rights of white and black equally.

...

BY THE time Hobhouse died in 1926 she was a lonely woman who had often been vilified for her humanitarian work in SA, and also in Germany during the First World War. She had narrowly missed being charged with treason for meeting with German officials during the First World War, and she yearned for acknowledgement. That she only got posthumously.

Hobhouse is still the only foreigner to have had a state funeral in SA, and she was made an honorary South African citizen for her humanitarian work here.

Pretty much everything was against Hobhouse, right from the start. Born in April 1860 to an upper middle-class British family, she was expected only to be a dutiful wife.

Yet, even as a 16-year-old, Hobhouse realised what mattered to her was unlike what mattered to others. She yearned to see humanity working in harmonious tandem, despite differences.

Not until she was 35 and her very conservative father dead was she able to start the work for which she became famous and notorious.

"What surprised me the most," Brits says, "is the wonderful endurance she had. There were times when she was hungry, when she couldn’t wash for five days. She had no significant other to confide in. She did write letters, but they took three to four weeks to get there, yet she didn’t at a point say, ‘Listen, I’ve had enough.’

"There are very few people in the world who are brave enough to do that (campaign, against popular sentiment, for the rights of the supposed enemy), and she did it again in another war."

Courage, as has often been pointed out, is not the absence of fear, it is carrying on despite fear. Hobhouse had courage in spades. She continued her battle despite the social mores of the time, personal depression, other health problems, and the opprobrium of friends, family, and compatriots.

Humanity needs people such as Hobhouse, prepared to walk their own path, determined to point out society’s flaws and work to fix them. They don’t come around often.

Hobhouse was often afraid, yet her concern for the underdog was always bigger than her personal needs. Starting with her teenage visits to people her father wanted ostracised, she went on to campaign for the rights of Boer women and children, and the rights of German women and children during the First World War, and worked for women’s suffrage.

Ironically, she missed out on being allowed to vote in the UK after the passing of legislation in 1918 granting the vote to women over 30 who were married, owned property, or were graduates.

...

DYING in 1926, Hobhouse wrote: "Little life remains in me, (and) I do feel some sort of reinstitution in the public mind of England and documentary evidence of it, would do more than anything else to brighten the remaining time. Few know what a heavy burden it has been to carry for quarter of a century."

"It’s a sad story," Brits says. "She was fiercely patriotic towards England… She has been misunderstood from so many sides, and by so many people. The last six letters she wrote I transcribed. They made me quite sad."

Sad it might be, but it is also a story of phenomenal courage. The truth is Hobhouse was remarkable, but there is another truth too — there are other unsung female heroes from yesteryear whose stories need to be told. Some crossed the Sahara at a time when few Europeans had done so; some developed mathematics we use today. Brits has been bitten by the bug. She foresees more on Hobhouse coming from her hand, and then perhaps something on one of these other female achievers.

• August is Women’s Month. August 19 is World Humanitarian Day