Elections in Africa usher in positive changes

by Paul Clark

2016-08-02 05:50:37.0

IN 2015, several key elections took place across Africa that provided hope that politics on the continent had matured, and future changes would come via the ballot box. The most momentous of these was the peaceful transition of power from the People’s Democratic Party to the All Progressives Congress in Nigeria, when former president Goodluck Jonathan conceded defeat to Muhammadu Buhari. This transition came in only the fourth election since the end of military rule in 1999.

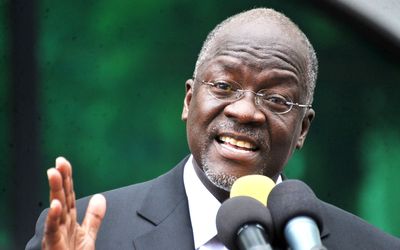

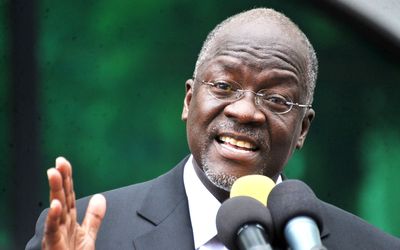

In East Africa, we saw a change of administration in Tanzania when John Magufuli, the surprise candidate of the governing Chama Cha Mapinduzi party, won a hotly contested race against former prime minister Edward Lowassa, who had crossed the floor to the opposition. Like Buhari in Nigeria, Magufuli’s campaign was focused strongly on a commitment to reduce corruption, and so far, he appears to be acting on his election promise.

Zambia held a presidential by-election in January 2015 after the death in office of president Michael Sata. The opposition performed strongly, but its candidate, Hakainde Hichilema, lost to the governing party’s Edgar Lungu by 1.7%. Given this tight race, we could well see a change in government when Zambians go to the polls on August 11.

By contrast, 2016 has seen some setbacks in smaller and less well-run countries. In Burundi, President Pierre Nkurunziza used a legal loophole to stand for a third term in office after failing to rally sufficient support for a constitutional amendment.

During the Ugandan poll in February, a social media "blackout" was imposed on Facebook, Twitter and WhatsApp, a move President Yoweri Museveni called a "security measure to avert lies".

The Republic of the Congo also saw internet and cellphone coverage blocked as citizens headed to the polls in March. President Denis Sassou-Nguesso was re-elected for a further five-year term after changes to the constitution removed age and term limits for the president. Next door, Rwanda’s Paul Kagame, called for a referendum to change term limits. The referendum, held in December 2015, saw more than 98% of voters approve the changes.

Not surprisingly, President Kagame announced after this endorsement that he would run for office again in elections that are due to be held in 2017.

READ THIS: Tips for the US on how to court Africa’s democracies

Despite these setbacks, we have also seen some positive changes. President Macky Sall convinced Senegalese voters to approve changes to their constitution during a referendum in March. Changes included reducing his term of office from seven years to five, as well as strengthening the rights of citizens and opposition party members. We have also seen citizens reject constitutional changes in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and, as mentioned above, in Burundi.

There is a general sense that democracy is improving across the continent, aided by improved communication and a younger generation that hankers after better economic management. The Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) Democracy Index, rates 167 countries on 60 indicators grouped in five categories.

In terms of this analysis, even countries that hold elections can be classified as authoritarian regimes if the environment is not conducive to a fair vote. Examples include Zimbabwe and Egypt. Based on the index’s 2015 calculations, Mauritius — regarded as a full democracy — is Africa’s most democratic country, ranking 18th out of 167 countries, ahead of the US at 20. Botswana (28), Cape Verde (32), SA (37) and Ghana (53) make up the rest of the top five African states. All are classified as "flawed democracies".

In the past five years the improvement in democracy means that less than 50% of Africans now live in authoritarian regimes, down from 73% in 2010. Africa’s average score is also improving, although more than half of the world’s 51 authoritarian regimes — at 27 — are still found on the continent.

• Clark is Africa equity specialist at Ashburton Investments

Tanzanian President John Magufuli has put his energies into revitalising and developing the country. Picture: REUTERS/SADI SAID

IN 2015, several key elections took place across Africa that provided hope that politics on the continent had matured, and future changes would come via the ballot box. The most momentous of these was the peaceful transition of power from the People’s Democratic Party to the All Progressives Congress in Nigeria, when former president Goodluck Jonathan conceded defeat to Muhammadu Buhari. This transition came in only the fourth election since the end of military rule in 1999.

In East Africa, we saw a change of administration in Tanzania when John Magufuli, the surprise candidate of the governing Chama Cha Mapinduzi party, won a hotly contested race against former prime minister Edward Lowassa, who had crossed the floor to the opposition. Like Buhari in Nigeria, Magufuli’s campaign was focused strongly on a commitment to reduce corruption, and so far, he appears to be acting on his election promise.

Zambia held a presidential by-election in January 2015 after the death in office of president Michael Sata. The opposition performed strongly, but its candidate, Hakainde Hichilema, lost to the governing party’s Edgar Lungu by 1.7%. Given this tight race, we could well see a change in government when Zambians go to the polls on August 11.

By contrast, 2016 has seen some setbacks in smaller and less well-run countries. In Burundi, President Pierre Nkurunziza used a legal loophole to stand for a third term in office after failing to rally sufficient support for a constitutional amendment.

During the Ugandan poll in February, a social media "blackout" was imposed on Facebook, Twitter and WhatsApp, a move President Yoweri Museveni called a "security measure to avert lies".

The Republic of the Congo also saw internet and cellphone coverage blocked as citizens headed to the polls in March. President Denis Sassou-Nguesso was re-elected for a further five-year term after changes to the constitution removed age and term limits for the president. Next door, Rwanda’s Paul Kagame, called for a referendum to change term limits. The referendum, held in December 2015, saw more than 98% of voters approve the changes.

Not surprisingly, President Kagame announced after this endorsement that he would run for office again in elections that are due to be held in 2017.

READ THIS: Tips for the US on how to court Africa’s democracies

Despite these setbacks, we have also seen some positive changes. President Macky Sall convinced Senegalese voters to approve changes to their constitution during a referendum in March. Changes included reducing his term of office from seven years to five, as well as strengthening the rights of citizens and opposition party members. We have also seen citizens reject constitutional changes in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and, as mentioned above, in Burundi.

There is a general sense that democracy is improving across the continent, aided by improved communication and a younger generation that hankers after better economic management. The Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) Democracy Index, rates 167 countries on 60 indicators grouped in five categories.

In terms of this analysis, even countries that hold elections can be classified as authoritarian regimes if the environment is not conducive to a fair vote. Examples include Zimbabwe and Egypt. Based on the index’s 2015 calculations, Mauritius — regarded as a full democracy — is Africa’s most democratic country, ranking 18th out of 167 countries, ahead of the US at 20. Botswana (28), Cape Verde (32), SA (37) and Ghana (53) make up the rest of the top five African states. All are classified as "flawed democracies".

In the past five years the improvement in democracy means that less than 50% of Africans now live in authoritarian regimes, down from 73% in 2010. Africa’s average score is also improving, although more than half of the world’s 51 authoritarian regimes — at 27 — are still found on the continent.

• Clark is Africa equity specialist at Ashburton Investments