THERE are some things better left alone. A wasp nest, for example, is a fine thing to leave alone. A rabid dog fits right into that category.

Funny I should mention wasps being left alone because that’s exactly what David Lagercrantz should have done when approached to write a sequel to the Millennium trilogy by Stieg Larsson. To be blunt, when Larsson died aged 50 in 2004 his publishers should have let the series die with him instead of finding another author to crank out another book in a similar vein.

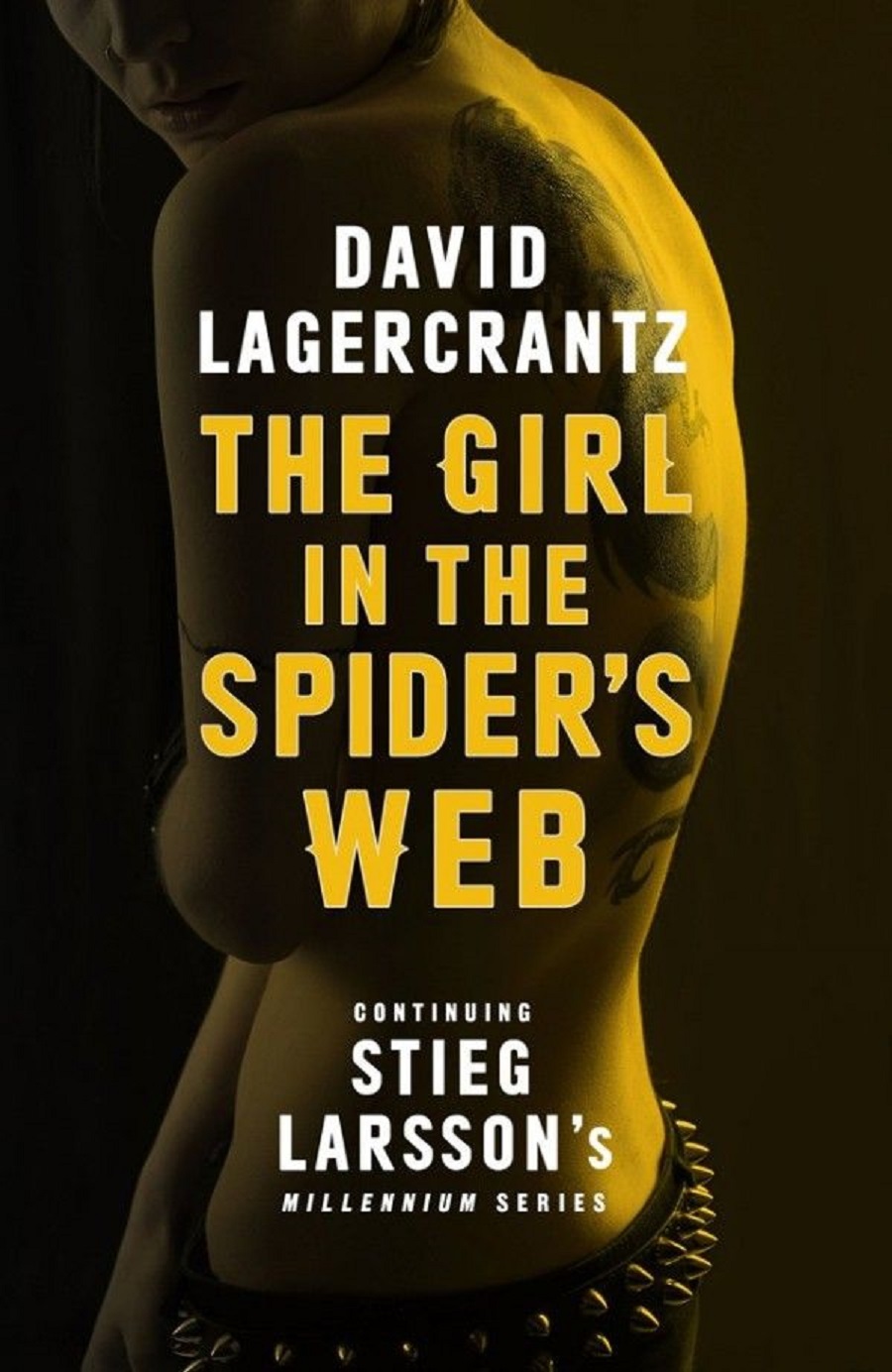

The book, The Girl in the Spider’s Web, which follows on from three others with similar titles in that they all started with "The Girl … ", was just not as gripping a read as Larsson’s efforts. In fact, in some instances, it was clumsy.

The Spider’s Web story starts with a cast of characters beautifully constructed by Larsson. Helpfully, it also has a map of part of Stockholm. It was as if the publishers gave Lagercrantz a blueprint of names and places and told him to write something to milk the Mikael Blomkvist and Lisbeth Salander money teat just a little more.

Lagercrantz made a valiant effort, but much of the book comes across as interminable lectures on various things he’d researched ahead of writing the Spider’s Web. If you’re into computers, hacking and sophisticated maths you’ll have a fun read. Otherwise, you’ll find yourself skimming the page to get to the bits where the story advances.

Lagercrantz introduces the obvious avenue for a sequel as subtly as the makers of the Spiderman movie franchises set up their next flicks.

There’s a part of the book that jars and this reviewer found himself rolling his eyes and saying "ja, right" at a point at which an eight-year-old autistic boy, who witnessed the murder of a father who saved him from years of neglect at the hands of his mother’s boyfriend, turns out to be a savant with incredible mathematical abilities that leads Salander (whose hacker name is Wasp) to crack an impossibly difficult code.

Now, you tell me how a little boy who was deprived of real education and grew up in a home in which all he was given was puzzles to keep him occupied between beatings manages to understand Salander’s curt instruction to find the prime number factors of very, very large numbers using elliptical curves.

I looked these curves up on the internet and, granted, I’m no savant, but this is serious maths and not something you’d just know or immediately grasp and apply in a single evening after watching your dad being shot dead in front of you and then narrowly escaping an assassination attempt. No.

I don’t mind fiction, but when it is clumsily bent into an unnatural yet convenient shape to give the author the outcome he wants, then it’s just annoying. I’m one of the last in my circle of friends who still reads fiction and after ploughing through nonsense such as this, I find myself pondering the wisdom of my reading habits.

An attempt to introduce a killer — a Russian military veteran — as a man with a conscience just didn’t work but it, again, introduced a handy plot point that allowed the book to build around the child, who is not only a maths genius, but an artist at a level that allowed for the hitherto anonymous assassin to be identified and for his mother’s boyfriend and his mate to meet some justice. How convenient. How lame.

Blomkvist, the star journalist, and Salander, the misfit who is the smartest person ever to lay hands on a keyboard, are thinly sketched in the story, with Lagercrantz using Salander’s brutalised past as another key story point.

There are the almost obligatory passages in which the book’s protagonists walk the streets of Stockholm, with Lagercrantz clearly using the map so thoughtfully provided in the front of the book to give us each twist and turn.

Another map is provided later on in the book for the reader to follow a frantic dash to rescue the boy.

Lagercrantz brings in a misfit American computer boffin and there was a nagging feeling this was done as a way, possibly, of attracting a US audience for the book.

This book turned out to be a poor and flimsy echo of what was a gripping trilogy.

Here’s hoping the publishers are smart enough to draw a line under it and leave it alone, but money talks — never mind it adding absolutely nothing to what was an enthralling series and, arguably, detracting from it.

Change: 2.98%

Change: 3.39%

Change: 2.94%

Change: 3.00%

Change: 5.00%

Data supplied by Profile Data

Change: 2.19%

Change: 1.30%

Change: 2.98%

Change: 0.00%

Change: 1.73%

Data supplied by Profile Data

Change: -0.61%

Change: -0.22%

Change: -1.46%

Change: -1.57%

Change: -0.58%

Data supplied by Profile Data

Change: -0.35%

Change: 1.50%

Change: -0.57%

Change: 0.09%

Change: 7.81%

Data supplied by Profile Data