Nelson Mandela: a life remembered

by Nicky Oppenheimer

2013-12-10 07:05:16.0

HOW will we remember Nelson Mandela not only today when we are a nation in grief, but in the months and years ahead? As the man who at the most dangerous moment in our turbulent history, with our future balanced on a knife edge, and the decades-long prophecies of rage and conflict about to erupt in dreadful reality, saved us from ourselves? As the leader whose grace and generosity so embodied the very essence of his message of reconciliation that in those dangerous days leading to the birth of the new South Africa, he made us all willing slaves to his will?

Or as the president who gave us back our honour as a nation so that after years of international opprobrium we were once again proud and happy to proclaim that we were South Africans?

We will, of course, continue to wonder at these achievements of a man, already elderly, who had emerged from 27 years of imprisonment for his beliefs and been reviled for years by a vindictive state as a revolutionary and a terrorist, to lead a country that became under his transforming leadership a model and a lesson for other divided nations that the dream of reconciliation could become a reality. This alone will surely strain the credulity of future historians for they will not know, as we know, that what he did was rooted in what he was; that his actions were informed by the one quality that defines great leaders and that is so lacking in today’s war-torn and troubled world: moral authority.

I first met Nelson Mandela shortly after his release from prison and count myself exceptionally lucky and privileged to have been counted among his friends. I observed his remarkable ability to walk with kings and keep the common touch, his dignity at occasions of much pomp and circumstance coupled with a determination to meet and delight the “ordinary” men and women who make such occasions possible. I saw and wondered at the total lack of bitterness in a man who had more excuse than any of his fellows to be bitter; the genuine humility of one who had more reason to be proud than any other leader in the world today.

I admired his persistent refusal to deploy the race card as a means to garner popular support, his recognition that to do so would divide once again those whom he has united.

And I fell frequent and willing victim to his charm and his implacable will when he deployed these to enlist my support for a favourite cause or charity.

No one, I learned, could say “no” to Madiba. I enjoyed his infectious sense of fun and his simple love of life. Above all, I admired the determination of a man with more reason than anyone to look back in anger, to instead look forward in hope.

Much has been written over the years about the “Madiba magic” that helped to bring peace to South Africa, and many countries around the world have sought the healing touch of a man internationally regarded, like Gandhi, as a secular saint of our time. By definition, however, magic and sainthood defy imitation; they imply unique qualities to which lesser mortals and lesser leaders cannot possibly aspire.

But this is too easy and undemanding a route; it exonerates us from even trying, as we must, to learn the lessons of his life and his leadership. History — and his story — demands more of us if we are to remember him as we must and as he would wish, not in sculptures in stone or bronze or in words, but by following his example and remembering his message that the new South Africa was forged not in conflict, but in reconciliation.

Twenty-three years ago, fortune smiled on South Africa when Nelson Mandela emerged at last from prison to prove that sometimes, very occasionally, when the hour comes so does the man.

A country so prodigal in its prejudices and fears could hardly be said to have deserved its luck.

If in the years ahead we squander that remarkable inheritance on ancient grievances and prejudices, we will deface his memory no matter how often we invoke his name.

We will remember him best by continuing to forge the country he wanted; only then will we be able to say: if you seek his monument, look around — at a people at peace with each other and with themselves.

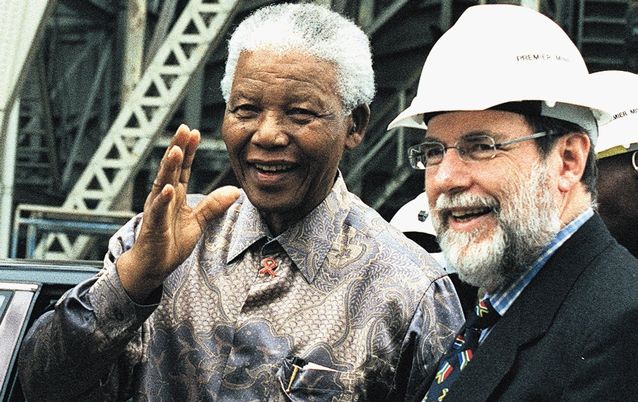

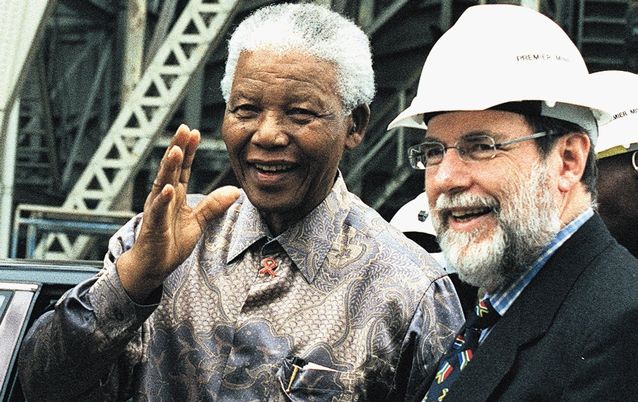

Nelson Mandela and De Beers chairman Nicky Oppenheimer. Picture: BONILE BAM

HOW will we remember Nelson Mandela not only today when we are a nation in grief, but in the months and years ahead? As the man who at the most dangerous moment in our turbulent history, with our future balanced on a knife edge, and the decades-long prophecies of rage and conflict about to erupt in dreadful reality, saved us from ourselves? As the leader whose grace and generosity so embodied the very essence of his message of reconciliation that in those dangerous days leading to the birth of the new South Africa, he made us all willing slaves to his will?

Or as the president who gave us back our honour as a nation so that after years of international opprobrium we were once again proud and happy to proclaim that we were South Africans?

We will, of course, continue to wonder at these achievements of a man, already elderly, who had emerged from 27 years of imprisonment for his beliefs and been reviled for years by a vindictive state as a revolutionary and a terrorist, to lead a country that became under his transforming leadership a model and a lesson for other divided nations that the dream of reconciliation could become a reality. This alone will surely strain the credulity of future historians for they will not know, as we know, that what he did was rooted in what he was; that his actions were informed by the one quality that defines great leaders and that is so lacking in today’s war-torn and troubled world: moral authority.

I first met Nelson Mandela shortly after his release from prison and count myself exceptionally lucky and privileged to have been counted among his friends. I observed his remarkable ability to walk with kings and keep the common touch, his dignity at occasions of much pomp and circumstance coupled with a determination to meet and delight the “ordinary” men and women who make such occasions possible. I saw and wondered at the total lack of bitterness in a man who had more excuse than any of his fellows to be bitter; the genuine humility of one who had more reason to be proud than any other leader in the world today.

I admired his persistent refusal to deploy the race card as a means to garner popular support, his recognition that to do so would divide once again those whom he has united.

And I fell frequent and willing victim to his charm and his implacable will when he deployed these to enlist my support for a favourite cause or charity.

No one, I learned, could say “no” to Madiba. I enjoyed his infectious sense of fun and his simple love of life. Above all, I admired the determination of a man with more reason than anyone to look back in anger, to instead look forward in hope.

Much has been written over the years about the “Madiba magic” that helped to bring peace to South Africa, and many countries around the world have sought the healing touch of a man internationally regarded, like Gandhi, as a secular saint of our time. By definition, however, magic and sainthood defy imitation; they imply unique qualities to which lesser mortals and lesser leaders cannot possibly aspire.

But this is too easy and undemanding a route; it exonerates us from even trying, as we must, to learn the lessons of his life and his leadership. History — and his story — demands more of us if we are to remember him as we must and as he would wish, not in sculptures in stone or bronze or in words, but by following his example and remembering his message that the new South Africa was forged not in conflict, but in reconciliation.

Twenty-three years ago, fortune smiled on South Africa when Nelson Mandela emerged at last from prison to prove that sometimes, very occasionally, when the hour comes so does the man.

A country so prodigal in its prejudices and fears could hardly be said to have deserved its luck.

If in the years ahead we squander that remarkable inheritance on ancient grievances and prejudices, we will deface his memory no matter how often we invoke his name.

We will remember him best by continuing to forge the country he wanted; only then will we be able to say: if you seek his monument, look around — at a people at peace with each other and with themselves.