THE worldwide outpouring of grief and praise at the death of Nelson Mandela is a truly astonishing phenomenon. I can think of no other political figure in modern times who has attracted such universal admiration. As the New York Times noted, the array of heads of state and government who came together for his funeral was akin to a sitting of the United Nations General Assembly.

Newspapers and TV stations around the world have given wall-to-wall coverage of his death, memorial service and funeral. The BBC alone ran a solid 48 hours on Mandela last week.

I can understand why we South Africans feel so emotional about him. Mandela saved us from a terrible race war that would have ruined all our lives. By liberating his own oppressed people, he freed us white South Africans from the bondage of guilt and shame. So we all owe him deep gratitude.

But what of the rest of the world? What has he meant to them? It is not as though he saved a world power from a disaster that would have affected them all. South Africa is small fry in global politics.

Nor has he always been a peacemaker, as Mohandas Gandhi and Martin Luther King Jr were.

Mandela was the founder of a revolutionary army bent on overthrowing the government of his country by force. He was regarded as a "terrorist" by most of the western world, which would have nothing to do with his organisation, so that it had to turn to the communist East to find support.

Yet now they all glorify him to a point verging on reverence. Why?

I think the answer is that there is a pervasive sense of uncertainty and insecurity among people everywhere.

The world is shrinking fast into Marshall McLuhan’s global village, and the neighbourhood is becoming a seriously conflicted place. Mandela’s image as a miracle peacemaker plays into that.

We have just emerged from the bloodiest century in all of human history. The First World War was supposed to be the war to end all wars; instead, it turned out to be the war to end all peace.

Since then, we have had another, much bigger world war, the Cold War, the Korean War, the Vietnam War; according to Wikipedia, 247 wars, large and small, in the 20th century, with about 400-million people killed.

It witnessed monstrous deeds — the Holocaust, the Armenian genocide, the Rwandan genocide, and the use of weapons of mass destruction, chemical and nuclear. All that killing was committed by human beings against other human beings of different cultures or colours or faiths or ethnicities or ideologies. Against "the other", people who were different and therefore feared and hated.

Now we have entered the 21st century and the pace of global shrinkage is accelerating. Today we can communicate instantly by satellite with anyone anywhere on earth. We can fly anywhere in a matter of hours.

Meanwhile, the wretched of the earth are migrating from poorer lands to richer lands. They are crossing the Mexican border into the US and the Mediterranean into southern Italy, and thence into the rest of the European Union, itself a union of 28 states.

They are moving from Turkey into Germany and from Sudan into Israel. Easterners are moving west and southerners are moving north; former colonialists are colonising their old metropoles in an ironic twist of history.

As this happens, the rich and comfortable are trying to keep out the great unwashed. They are building border fences and barrier walls, requiring expensive visas and passing stringent immigration laws. These are pass laws, really. Influx control. Apartheid.

Like the old South Africa, the developed world is trying to keep out "the other".

But, like us, they will find that apartheid doesn’t work and they will have to come to terms with the fact that the whole world is integrating.

That is not easy, as we know. Because cultural conflict leads to violence. Americans have experienced 9/11, bombs have gone off in London buses and in its underground railway system. There have been bombs in Nairobi and New York, at the Boston Marathon and in Nigeria and Sudan. There have been car bombs and aircraft bombs and there is almost permanent conflict throughout the ethnically diverse Middle East.

Terrorism is everywhere and the pilotless drone is the new tool of targeted assassination. Nowhere is safe and everyone lives in a penumbra of fear.

Faced with this state of our global village, the late Samuel Huntington predicted the next great war would not be about ideological differences but between incompatible civilisations. He pointed a finger at the Muslim world and urged the US to be prepared. US president George Bush took him seriously and declared his war on terrorism and "the axis of evil".

But Huntington was wrong. For the sensible among us know there can be no winner of such a global holy war in the nuclear age, just as Mandela realised there could be no winner of a race war in South Africa. Only a wasteland would be left. So he found a better way.

That, I sense, is why everyone looks to Mandela as the symbolic peacemaker that this troubled global village so desperately needs. His way was to conquer fear of "the other" in South Africa so that he could bring the warring factions together in a spirit of reconciliation.

He succeeded because he was able himself to set an example of forgiveness. If Mandela was able to forgive white South Africans for oppressing his people for 350 years, and for the 27 years they incarcerated him, destroyed the prime of his life and brutalised his family, then surely everyone else could forgive too.

Forgiveness, as Jonny Steinberg has written, is a tricky thing.

It has to be genuine or it won’t work, and that requires huge self-confidence, political shrewdness and emotional intelligence, all of which Mandela had in abundance.

Empathy is the key; the ability to understand your adversary. What made him oppress you and your people? What made him so vindictive?

Mandela set about acquiring that understanding while he was in prison. He probed the mind-set of his harshest jailers and he began reading Afrikaans literature, even its poetry.

He came to understand the Afrikaners’ powerful sense of identity and love of the soil of Africa. They feared losing all that if ever there was universal franchise. They feared vengeance and they feared being swamped out of existence by sheer numbers.

Out of that came Mandela’s realisation that the aggression stemmed from fear.

Remove the fear and the aggression would recede, making reconciliation possible. So that is what he did.

That is what I sense the people of the world yearn for.

Leaders who try to understand their adversaries, who are capable of realising that they fear you if you are powerful and overbearing, and who will work to reduce that fear so there can be less aggression in our global village.

So let us celebrate what is perhaps the greatest of all Mandela’s achievements — turning the polecat of the world into its pathfinder.

• Sparks is a former editor of the Rand Daily Mail.

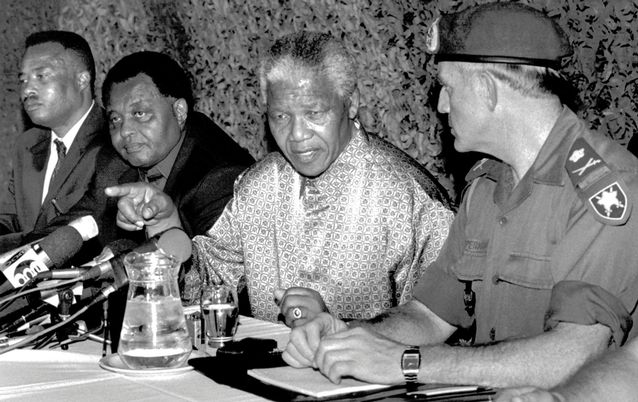

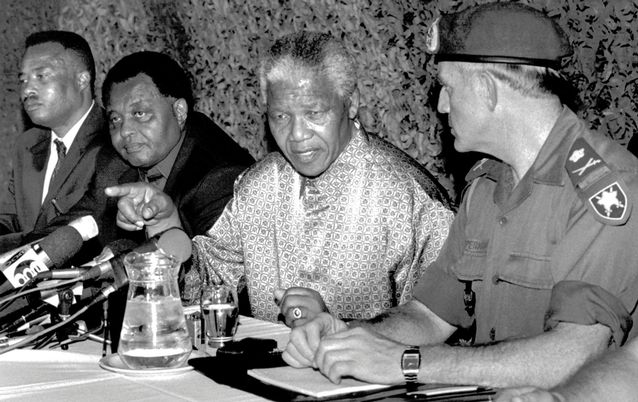

PEACE TALK: Nelson Mandela in discussions in the early 1990s after his release from prison. Picture: GETTY IMAGES

THE worldwide outpouring of grief and praise at the death of Nelson Mandela is a truly astonishing phenomenon. I can think of no other political figure in modern times who has attracted such universal admiration. As the New York Times noted, the array of heads of state and government who came together for his funeral was akin to a sitting of the United Nations General Assembly.

Newspapers and TV stations around the world have given wall-to-wall coverage of his death, memorial service and funeral. The BBC alone ran a solid 48 hours on Mandela last week.

I can understand why we South Africans feel so emotional about him. Mandela saved us from a terrible race war that would have ruined all our lives. By liberating his own oppressed people, he freed us white South Africans from the bondage of guilt and shame. So we all owe him deep gratitude.

But what of the rest of the world? What has he meant to them? It is not as though he saved a world power from a disaster that would have affected them all. South Africa is small fry in global politics.

Nor has he always been a peacemaker, as Mohandas Gandhi and Martin Luther King Jr were.

Mandela was the founder of a revolutionary army bent on overthrowing the government of his country by force. He was regarded as a "terrorist" by most of the western world, which would have nothing to do with his organisation, so that it had to turn to the communist East to find support.

Yet now they all glorify him to a point verging on reverence. Why?

I think the answer is that there is a pervasive sense of uncertainty and insecurity among people everywhere.

The world is shrinking fast into Marshall McLuhan’s global village, and the neighbourhood is becoming a seriously conflicted place. Mandela’s image as a miracle peacemaker plays into that.

We have just emerged from the bloodiest century in all of human history. The First World War was supposed to be the war to end all wars; instead, it turned out to be the war to end all peace.

Since then, we have had another, much bigger world war, the Cold War, the Korean War, the Vietnam War; according to Wikipedia, 247 wars, large and small, in the 20th century, with about 400-million people killed.

It witnessed monstrous deeds — the Holocaust, the Armenian genocide, the Rwandan genocide, and the use of weapons of mass destruction, chemical and nuclear. All that killing was committed by human beings against other human beings of different cultures or colours or faiths or ethnicities or ideologies. Against "the other", people who were different and therefore feared and hated.

Now we have entered the 21st century and the pace of global shrinkage is accelerating. Today we can communicate instantly by satellite with anyone anywhere on earth. We can fly anywhere in a matter of hours.

Meanwhile, the wretched of the earth are migrating from poorer lands to richer lands. They are crossing the Mexican border into the US and the Mediterranean into southern Italy, and thence into the rest of the European Union, itself a union of 28 states.

They are moving from Turkey into Germany and from Sudan into Israel. Easterners are moving west and southerners are moving north; former colonialists are colonising their old metropoles in an ironic twist of history.

As this happens, the rich and comfortable are trying to keep out the great unwashed. They are building border fences and barrier walls, requiring expensive visas and passing stringent immigration laws. These are pass laws, really. Influx control. Apartheid.

Like the old South Africa, the developed world is trying to keep out "the other".

But, like us, they will find that apartheid doesn’t work and they will have to come to terms with the fact that the whole world is integrating.

That is not easy, as we know. Because cultural conflict leads to violence. Americans have experienced 9/11, bombs have gone off in London buses and in its underground railway system. There have been bombs in Nairobi and New York, at the Boston Marathon and in Nigeria and Sudan. There have been car bombs and aircraft bombs and there is almost permanent conflict throughout the ethnically diverse Middle East.

Terrorism is everywhere and the pilotless drone is the new tool of targeted assassination. Nowhere is safe and everyone lives in a penumbra of fear.

Faced with this state of our global village, the late Samuel Huntington predicted the next great war would not be about ideological differences but between incompatible civilisations. He pointed a finger at the Muslim world and urged the US to be prepared. US president George Bush took him seriously and declared his war on terrorism and "the axis of evil".

But Huntington was wrong. For the sensible among us know there can be no winner of such a global holy war in the nuclear age, just as Mandela realised there could be no winner of a race war in South Africa. Only a wasteland would be left. So he found a better way.

That, I sense, is why everyone looks to Mandela as the symbolic peacemaker that this troubled global village so desperately needs. His way was to conquer fear of "the other" in South Africa so that he could bring the warring factions together in a spirit of reconciliation.

He succeeded because he was able himself to set an example of forgiveness. If Mandela was able to forgive white South Africans for oppressing his people for 350 years, and for the 27 years they incarcerated him, destroyed the prime of his life and brutalised his family, then surely everyone else could forgive too.

Forgiveness, as Jonny Steinberg has written, is a tricky thing.

It has to be genuine or it won’t work, and that requires huge self-confidence, political shrewdness and emotional intelligence, all of which Mandela had in abundance.

Empathy is the key; the ability to understand your adversary. What made him oppress you and your people? What made him so vindictive?

Mandela set about acquiring that understanding while he was in prison. He probed the mind-set of his harshest jailers and he began reading Afrikaans literature, even its poetry.

He came to understand the Afrikaners’ powerful sense of identity and love of the soil of Africa. They feared losing all that if ever there was universal franchise. They feared vengeance and they feared being swamped out of existence by sheer numbers.

Out of that came Mandela’s realisation that the aggression stemmed from fear.

Remove the fear and the aggression would recede, making reconciliation possible. So that is what he did.

That is what I sense the people of the world yearn for.

Leaders who try to understand their adversaries, who are capable of realising that they fear you if you are powerful and overbearing, and who will work to reduce that fear so there can be less aggression in our global village.

So let us celebrate what is perhaps the greatest of all Mandela’s achievements — turning the polecat of the world into its pathfinder.

• Sparks is a former editor of the Rand Daily Mail.

News and views on the death, and life, of former president Nelson Mandela, with tributes and photographs

News and views on the death, and life, of former president Nelson Mandela, with tributes and photographs