IT’s the strangest feeling in the world to be of an age when your childhood heroes begin dying. David Bowie, Prince, and now Muhammad Ali have all died this year, and the year is not halfway yet.

Comedian and actor Chris Rock has captured a bit of the moment, tweeting alongside pictures of Prince and Ali, "I wish this year would stop already: it’s just too much."

I remember as a high school student listening on a shortwave radio to commentary of the classic Rumble in the Jungle match in which Ali regained his heavyweight crown against George Foreman in the then Zaire. It was impossible to know what was going on. Radio commentary of boxing matches can sound like a satire of itself. It’s a continuous stream of uppercuts and left jabs, and circling and right hooks. Blows just come too fast for anyone to describe them with any accuracy.

But the sheer number of blows being landed by Foreman seemed to suggest that pre-match predictions that he would win were turning out to be correct. And then, all of sudden, he was down and out. Ali was King again. The King of Everything.

The fight changed the way he was regarded throughout the world. The big-mouth, anti-Vietnam war campaigner suddenly emerged out of it an icon.

His artistry in the ring, his brutal streak, his contradictory playfulness, his strange religion and amazing photogenic appeal combined into a kind of symbolic unity.

He had forced himself forward in a supreme act of will and, in doing so, he shares so much with the other two celebrity deaths so far this year.

Like Bowie, who was so much more of an image than a musician, and Prince, the emblem of brashness and gentility, Ali shares an odd quality: they are all ambidextrous characters blazing their own individual paths.

What a contrast to the heroes of our day. When I listen to the post-match interviews with modern tennis players after big tournaments, they are so thoughtful and kind to each other that it feels scripted. They probably are scripted.

They are so deferential, calmly professional and media astute, you can sense the presence of the small army of endorsement contractors hovering in the background.

What Ali and the host of other celebrities of the ’60s and ’70s gave us was something entirely different — a celebration of the raw, burning power of individualism.

One of the most enduring criticisms of Ali was his narcissism.

But, unlike modern-day narcissism, his was more the narcissism of self-promotion than the narcissism of personal vanity. Dave Kindred, an Ali biographer quoted in the New York Times, put it this way: "We forgive Muhammad Ali his excesses because we see in him the child in us, and if he is foolish or cruel, if he is arrogant, if he is outrageously in love with his reflection, we forgive him because we no more can condemn him than condemn a rainbow for dissolving into the dark. Rainbows are born of thunderstorms, and Muhammad Ali is both."

This may be a kind of pretension, but I see a lot of Nelson Mandela in Ali, and vice versa. They share some aspects of their era: a strident individualism combined with both a streak of wilfulness and a deep sense of caring and kindness.

Individualism was a mark of the age, and it’s hard to understand now what a new and vital thing that was in ’60s. Dressing in a deliberately offensive way, men growing their hair long and denying society’s strictures were all an instinctive rebellion against the "rules" of society in general, and a whole basket of the "isms" of the age: sexism, fascism and, to some extent, communism.

In taking his stand, Ali and his many and varied cohorts broke down barriers in more ways and with more depth than I imagine people generally now appreciate.

They made some terrible mistakes too: endorsing sloth, drug dependency and, most of all, failing to understand economics, and particularly the baleful economics of communism.

Yet, in so many ways, they shaped the modern era. I always thought their contribution to society might have been great, but their effect on business was slight, until I began reading about Apple founder Steve Jobs.

Jobs’s notion of personal computing came straight out of the audacious individualist handbook.

We are saying goodbye to a generation whose contribution seems at once fundamental and also lost. It’s both a great pity and inevitable.

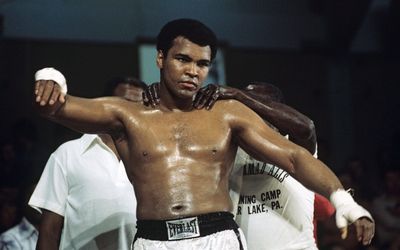

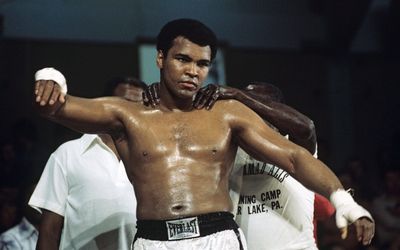

A picture made available on June 4 2016 and dated May 25 1976 shows Muhammad Ali training ahead of his heavyweight fight against British Richard Dunn at the Olympiahalle in Munich, Germany. Picture: EPA/ISTVAN BAJZAT

IT’s the strangest feeling in the world to be of an age when your childhood heroes begin dying. David Bowie, Prince, and now Muhammad Ali have all died this year, and the year is not halfway yet.

Comedian and actor Chris Rock has captured a bit of the moment, tweeting alongside pictures of Prince and Ali, "I wish this year would stop already: it’s just too much."

I remember as a high school student listening on a shortwave radio to commentary of the classic Rumble in the Jungle match in which Ali regained his heavyweight crown against George Foreman in the then Zaire. It was impossible to know what was going on. Radio commentary of boxing matches can sound like a satire of itself. It’s a continuous stream of uppercuts and left jabs, and circling and right hooks. Blows just come too fast for anyone to describe them with any accuracy.

But the sheer number of blows being landed by Foreman seemed to suggest that pre-match predictions that he would win were turning out to be correct. And then, all of sudden, he was down and out. Ali was King again. The King of Everything.

The fight changed the way he was regarded throughout the world. The big-mouth, anti-Vietnam war campaigner suddenly emerged out of it an icon.

His artistry in the ring, his brutal streak, his contradictory playfulness, his strange religion and amazing photogenic appeal combined into a kind of symbolic unity.

He had forced himself forward in a supreme act of will and, in doing so, he shares so much with the other two celebrity deaths so far this year.

Like Bowie, who was so much more of an image than a musician, and Prince, the emblem of brashness and gentility, Ali shares an odd quality: they are all ambidextrous characters blazing their own individual paths.

What a contrast to the heroes of our day. When I listen to the post-match interviews with modern tennis players after big tournaments, they are so thoughtful and kind to each other that it feels scripted. They probably are scripted.

They are so deferential, calmly professional and media astute, you can sense the presence of the small army of endorsement contractors hovering in the background.

What Ali and the host of other celebrities of the ’60s and ’70s gave us was something entirely different — a celebration of the raw, burning power of individualism.

One of the most enduring criticisms of Ali was his narcissism.

But, unlike modern-day narcissism, his was more the narcissism of self-promotion than the narcissism of personal vanity. Dave Kindred, an Ali biographer quoted in the New York Times, put it this way: "We forgive Muhammad Ali his excesses because we see in him the child in us, and if he is foolish or cruel, if he is arrogant, if he is outrageously in love with his reflection, we forgive him because we no more can condemn him than condemn a rainbow for dissolving into the dark. Rainbows are born of thunderstorms, and Muhammad Ali is both."

This may be a kind of pretension, but I see a lot of Nelson Mandela in Ali, and vice versa. They share some aspects of their era: a strident individualism combined with both a streak of wilfulness and a deep sense of caring and kindness.

Individualism was a mark of the age, and it’s hard to understand now what a new and vital thing that was in ’60s. Dressing in a deliberately offensive way, men growing their hair long and denying society’s strictures were all an instinctive rebellion against the "rules" of society in general, and a whole basket of the "isms" of the age: sexism, fascism and, to some extent, communism.

In taking his stand, Ali and his many and varied cohorts broke down barriers in more ways and with more depth than I imagine people generally now appreciate.

They made some terrible mistakes too: endorsing sloth, drug dependency and, most of all, failing to understand economics, and particularly the baleful economics of communism.

Yet, in so many ways, they shaped the modern era. I always thought their contribution to society might have been great, but their effect on business was slight, until I began reading about Apple founder Steve Jobs.

Jobs’s notion of personal computing came straight out of the audacious individualist handbook.

We are saying goodbye to a generation whose contribution seems at once fundamental and also lost. It’s both a great pity and inevitable.