How to read the tea leaves, grown and brewed in China

by Darias Jonker,

2015-12-04 05:58:20.0

THE sixth ministerial and summit meetings of the Forum on China-Africa Co-operation take place in the context of a cooling Chinese economy, a resultant decline in global commodity prices with a significant economic effect on the continent, the South African economy in particular.

It is, therefore, useful to consider what the meetings may herald for the future of our country: how the China-Africa relationship has developed, what this means for SA and how policy makers in the government and in the African National Congress (ANC) may plan accordingly.

As African countries gained independence, Maoist China supported liberation movements through ideological solidarity and political alliances in international institutions. Following the policy reforms implemented by Deng Xiaoping in 1978, China started to expand its economic relations with Africa. In the 1980s and 1990s, the pace of Chinese economic and diplomatic activity on the continent increased steadily as China’s economic growth trajectory required it to access new markets and secure supplies of natural resources. A more confident diplomatic posture saw China using its relationships with African countries to build support for its agenda as a global power.

The forum was established in 2000 to create an overarching framework for China to engage the continent. It is convened every three years, alternating between Beijing and an African capital. The meetings usually conclude with a political declaration underscoring the strength and goodwill of China-Africa relations and an action plan announcing China’s economic and developmental projects in Africa over coming years.

On the bilateral level, political relations between the People’s Republic of China and the ANC-led government have increased significantly after official recognition in 1997, when SA adopted the "One China" policy and amended its relations with Taiwan. Senior government officials from the two countries including the presidents, meet regularly and China is arguably SA’s most important international partner outside the continent. The Brics grouping adds another important layer to the bilateral relationship as the countries also closely co-operate in this club of emerging powers.

However, the South African government has been criticised for cosying up to a global power that does not necessarily interpret human rights in the manner called for by our Bill of Rights or Constitution. The Dalai Lama visa application debacle is frequently used as an example of the government kowtowing to China.

The ANC and alliance partner, the South African Communist Party (SACP) have entrenched their relations with the Communist Party of China (CPC). The parties regularly host delegations sent by their counterparts, and the CPC assists the ANC and the SACP through training opportunities and study tours.

The unprecedented economic activity in China in the past two decades saw bilateral trade increasing many times over since the mid-1990s. China is now SA’s largest trading partner, with mostly raw materials being exported from here and mostly manufactured goods being imported. This increase in Chinese activity in the local economy has been met with concern as domestic manufacturers struggle to compete with Chinese imports and large orders for raw materials remind some observers of a trading relationship from the colonial era.

Nonetheless, exporters enjoy access to a large and growing market, while consumers benefit from shelves stocked with a wider and more affordable range of products. Chinese companies have made large investments in our economy and their government develops our human resources through scholarships and training.

Under these circumstances, creating scenarios of how SA responds to China in the next 15 years allows policy makers to see the likely consequences of their actions.

An initial step in developing the scenarios would be to note the factors that drive China’s activities in SA that the preceding paragraphs show to be political, economic and cultural-social.

We then identify the predetermined elements of the scenarios, that is the certainties we can assume will remain constant throughout the 15-year period. These are that the CPC will remain in power; China will remain committed to growing and modernising its economy, will continue to internationalise and will not withdraw from the global stage; and the principles of Afro-Asian solidarity will remain a foundation of Chinese policy towards SA.

Now we have an idea of how China is likely to behave in our country. But how will SA behave? Experts in academia and think-tanks are calling for a number of policy recommendations the government should follow that would see China’s overtures being used to maximise benefits and avoid pitfalls. For the purpose of the scenarios, these policy decisions have already been considered by our leaders and we now find ourselves in the year 2030, looking back at two possible outcomes:

• Scenario 1, Wise moves: in this situation our leaders have a good understanding of China — some Cabinet members even speak Mandarin — and a more empowered, assertive policy towards China has tackled areas of concern including the unequal trading relationship. The economy is diversified and competitive, beneficiating most commodities before exporting them to China. State-owned enterprises and government departments use the lessons learnt from their Chinese counterparts radically to improve their efficiency. Thousands of South Africans return from China every year after graduating in engineering, medicine and information technology.

• Scenario 2, Missteps: Here, China has stepped in to help SA recover from a currency crisis caused by falling exports to China and an overreliance on Chinese consumer goods. The Cabinet travels to Beijing every quarter to meet its Chinese counterparts and provide progress reports on the rescue plan, which saw soft loans being extended in exchange for mining rights.

The stadiums and infrastructure required by Durban to host the 2024 Summer Olympics were built by Chinese labour, securing Chinese companies the right to mine the dunes around the iSimangaliso wetlands. Chinese tourists, the richest segment of the market, prefer to travel to the destinations for which they no longer need visas, mostly Europe and the US.

From these two portrayals of good and bad decision making, a realist may determine that the most likely scenario will see both types of decisions being made in more equal measures.

The exercise does, however, show us what could happen when the better angels of our nature are able to fly high. It also shows us what could happen if the lesser angels drag us down. Let us see how the angels fight it out in the next few days.

•J onker is a former South African diplomat and the founder of Jonker Advisory, who consults on government relations and strategic engagement

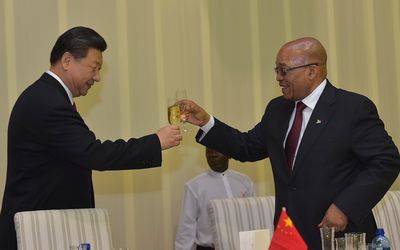

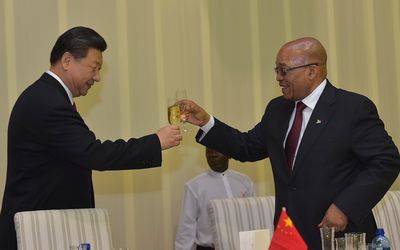

Chinese President Xi Jinping and President Jacob Zuma. Picture: CGIS

THE sixth ministerial and summit meetings of the Forum on China-Africa Co-operation take place in the context of a cooling Chinese economy, a resultant decline in global commodity prices with a significant economic effect on the continent, the South African economy in particular.

It is, therefore, useful to consider what the meetings may herald for the future of our country: how the China-Africa relationship has developed, what this means for SA and how policy makers in the government and in the African National Congress (ANC) may plan accordingly.

As African countries gained independence, Maoist China supported liberation movements through ideological solidarity and political alliances in international institutions. Following the policy reforms implemented by Deng Xiaoping in 1978, China started to expand its economic relations with Africa. In the 1980s and 1990s, the pace of Chinese economic and diplomatic activity on the continent increased steadily as China’s economic growth trajectory required it to access new markets and secure supplies of natural resources. A more confident diplomatic posture saw China using its relationships with African countries to build support for its agenda as a global power.

The forum was established in 2000 to create an overarching framework for China to engage the continent. It is convened every three years, alternating between Beijing and an African capital. The meetings usually conclude with a political declaration underscoring the strength and goodwill of China-Africa relations and an action plan announcing China’s economic and developmental projects in Africa over coming years.

On the bilateral level, political relations between the People’s Republic of China and the ANC-led government have increased significantly after official recognition in 1997, when SA adopted the "One China" policy and amended its relations with Taiwan. Senior government officials from the two countries including the presidents, meet regularly and China is arguably SA’s most important international partner outside the continent. The Brics grouping adds another important layer to the bilateral relationship as the countries also closely co-operate in this club of emerging powers.

However, the South African government has been criticised for cosying up to a global power that does not necessarily interpret human rights in the manner called for by our Bill of Rights or Constitution. The Dalai Lama visa application debacle is frequently used as an example of the government kowtowing to China.

The ANC and alliance partner, the South African Communist Party (SACP) have entrenched their relations with the Communist Party of China (CPC). The parties regularly host delegations sent by their counterparts, and the CPC assists the ANC and the SACP through training opportunities and study tours.

The unprecedented economic activity in China in the past two decades saw bilateral trade increasing many times over since the mid-1990s. China is now SA’s largest trading partner, with mostly raw materials being exported from here and mostly manufactured goods being imported. This increase in Chinese activity in the local economy has been met with concern as domestic manufacturers struggle to compete with Chinese imports and large orders for raw materials remind some observers of a trading relationship from the colonial era.

Nonetheless, exporters enjoy access to a large and growing market, while consumers benefit from shelves stocked with a wider and more affordable range of products. Chinese companies have made large investments in our economy and their government develops our human resources through scholarships and training.

Under these circumstances, creating scenarios of how SA responds to China in the next 15 years allows policy makers to see the likely consequences of their actions.

An initial step in developing the scenarios would be to note the factors that drive China’s activities in SA that the preceding paragraphs show to be political, economic and cultural-social.

We then identify the predetermined elements of the scenarios, that is the certainties we can assume will remain constant throughout the 15-year period. These are that the CPC will remain in power; China will remain committed to growing and modernising its economy, will continue to internationalise and will not withdraw from the global stage; and the principles of Afro-Asian solidarity will remain a foundation of Chinese policy towards SA.

Now we have an idea of how China is likely to behave in our country. But how will SA behave? Experts in academia and think-tanks are calling for a number of policy recommendations the government should follow that would see China’s overtures being used to maximise benefits and avoid pitfalls. For the purpose of the scenarios, these policy decisions have already been considered by our leaders and we now find ourselves in the year 2030, looking back at two possible outcomes:

• Scenario 1, Wise moves: in this situation our leaders have a good understanding of China — some Cabinet members even speak Mandarin — and a more empowered, assertive policy towards China has tackled areas of concern including the unequal trading relationship. The economy is diversified and competitive, beneficiating most commodities before exporting them to China. State-owned enterprises and government departments use the lessons learnt from their Chinese counterparts radically to improve their efficiency. Thousands of South Africans return from China every year after graduating in engineering, medicine and information technology.

• Scenario 2, Missteps: Here, China has stepped in to help SA recover from a currency crisis caused by falling exports to China and an overreliance on Chinese consumer goods. The Cabinet travels to Beijing every quarter to meet its Chinese counterparts and provide progress reports on the rescue plan, which saw soft loans being extended in exchange for mining rights.

The stadiums and infrastructure required by Durban to host the 2024 Summer Olympics were built by Chinese labour, securing Chinese companies the right to mine the dunes around the iSimangaliso wetlands. Chinese tourists, the richest segment of the market, prefer to travel to the destinations for which they no longer need visas, mostly Europe and the US.

From these two portrayals of good and bad decision making, a realist may determine that the most likely scenario will see both types of decisions being made in more equal measures.

The exercise does, however, show us what could happen when the better angels of our nature are able to fly high. It also shows us what could happen if the lesser angels drag us down. Let us see how the angels fight it out in the next few days.

•J onker is a former South African diplomat and the founder of Jonker Advisory, who consults on government relations and strategic engagement

Change: -1.04%

Change: -1.17%

Change: -1.77%

Change: -0.53%

Change: -2.66%

Data supplied by Profile Data

Change: 0.00%

Change: 0.00%

Change: -1.04%

Change: 0.00%

Change: 0.00%

Data supplied by Profile Data

Change: 0.44%

Change: 0.45%

Change: 0.78%

Change: 0.75%

Change: 0.11%

Data supplied by Profile Data

Change: 0.00%

Change: 0.00%

Change: 0.00%

Change: 0.00%

Change: 0.00%

Data supplied by Profile Data