FORTY years ago, drug-resistant tuberculosis (TB) was already a concern in rural Zululand. As we drove through northern KwaZulu-Natal this December, my mum recalled how, even then, 8%-10% of patients would fail to respond to the first line combination of drugs used to treat TB at the hospital in Hlabisa where she was superintendent.

As a notifiable and highly communicable disease, patients who tested positive for TB at the hospital were by law immediately admitted to hospital for a minimum of six weeks — to a maximum of three months — for treatment. In those days, the life-saving first line treatment was a combination of streptomycin, isoniazid and aminosalicylic acid, which were administered orally and intravenously either daily or every second day.

Earlier treatment showed that if the drugs were administered individually the bacteria would quickly develop a resistance to the drugs and the treatment would not work, but as a combination the drugs were far more effective — much like modern combination HIV therapy.

"The TB doctor would come up at least every six weeks to assess every patient and if they produced a negative sputum result and he was happy that they were healthy, he would discharge them back into the community," explained mum.

"These days, it seems hugely restrictive to force people to be in-patients, but the programme was very successful in dropping the rate of both reinfection and new infections."

It makes perfect sense that by stopping infected people from returning home, they were prevented from infecting others, and by ensuring that the full course of drugs was administered in hospital, patients would be completely healthy on discharge and hopefully avoid reinfections.

Yet even under such tight controls, some patients still developed a resistance to the first-line drugs. After three months of treatment if a patient was not responding and tested positive on a sputum test, they would be started on second-line drugs that once again needed to be signed off by the TB doctor.

Most patients recovered on the second-line treatment but in some cases they did not, and were discharged back into their communities while still carrying the disease in a mutated form.

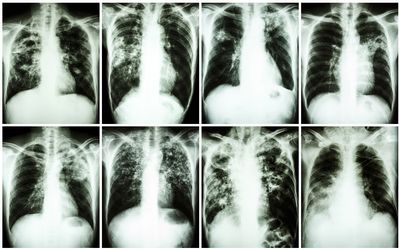

The bad news is that the resistance that TB bacteria developed in response to these early first-line treatment regimes has only become worse. Since then multi-drug resistant TB, or MDR-TB, and extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis, or XDR-TB, have become increasingly common in SA and the rest of the world.

In 2013, about 480,000 new cases of MDR-TB were identified and XDR-TB has been identified in 100 countries. The numbers might seem small on a global scale, but the problem is not limited to TB.

One of the more depressing implications of Darwin’s theory of natural selection is that resistance to antimicrobial agents is inevitable.

When treatment with an antimicrobial begins, nonresistant virus strains and bacteria are wiped out, leaving resistant cells to thrive.

Indeed, when Sir Alexander Fleming accepted his Nobel prize in 1945 for the discovery of penicillin, he warned in his speech that it was "not difficult to make microbes resistant to penicillin".

The inevitable result is that the more antimicrobial medicines are used, the more microbes will develop resistance to them, and the great strides made in treating and managing malaria and HIV could be reversed.

Although the treatment of MDR-TB and XDR-TB with second-and third-line drugs can still be successful, the treatment takes longer and the drugs are more expensive and have more side-effects. The same tends to apply to second-and third-line antibiotics used to treat other multi-drug resistant infections.

The rise of superbugs in hospitals — most notably MRSA or methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus — has garnered some media attention in recent years, but these stories take place against a robust public perception that modern medical science continues to make rapid progress in discovering new wonder drugs that treat more and more of our ills. The reality is somewhat further from the truth.

I grabbed a word with Jim O’Neill last month when he addressed hundreds of health ministers and parliamentarians from across the world who met as part of the Global TB Caucus to raise awareness for and commitment to the Global Plan to End TB.

Lord O’Neill is serving as the chairman of the British Review of Antimicrobial Resistance and hopes to not only raise awareness among consumers about the potential dangers of incorrect use of antimicrobials, but also to convince pharmaceutical companies to invest more in costly research and development of new drugs.

The review estimates that if left unchecked drug-resistant infections could kill an extra 10-million people across the world every year by 2050, and could cost the world about $100-trillion in lost output: more than the size of the current world economy and roughly equivalent to the world losing the output of the UK economy every year for 35 years.

One solution to the problem is to control the unnecessary use of antibiotics through better regulation and to better target the use of antibiotics through improved diagnostics. To this end, the £10m Longitude Prize aims to spur the development of a cheap, accurate, rapid, and easy to use test for bacterial infections that will allow doctors to better target their treatments.

Another is to encourage the production of new drugs through government incentives, something Lord O’Neill hopes to address at the next meeting of the Group of 20 nations.

Ultimately, without further research into new drugs, existing second-, third-and even experimental fourth-line drugs will also soon become limited in their efficacy — and the social and economic consequences will be disastrous.

THOSE of you who have been regular readers of my column over the years will know how fond I was of my father. Every morning he and the family dog, Basil, would inevitably wake me up as they clattered past my room on the way to pick up Business Day from the front door.

Dad passed away on December 16 last year after a brief battle with cancer. I love you and will miss you, Dad.

Change: -0.95%

Change: -1.26%

Change: -1.23%

Change: -0.89%

Change: -2.34%

Data supplied by Profile Data

Change: 0.00%

Change: 0.00%

Change: -0.95%

Change: 0.00%

Change: 0.00%

Data supplied by Profile Data

Change: -0.03%

Change: -0.01%

Change: 0.01%

Change: 0.00%

Change: -0.58%

Data supplied by Profile Data

Change: 0.00%

Change: 0.00%

Change: 0.00%

Change: 0.00%

Change: 0.00%

Data supplied by Profile Data