LAST week, the International Monetary Fund cut its growth forecast for SA to 0.7% for this year.

The Reuters consensus forecast is now 0.9%, and some economists have taken theirs down to 0.2%.

At any other time, this might seem a moment for monetary policy to go slow on doing anything that might further undermine growth prospects. As it is, it is not a matter of whether the Reserve Bank’s monetary policy committee (MPC) will hike rates when it meets this week, but a matter of how much.

That’s because the way the world is going, and the position in which SA finds itself, there is surely no other option. By how much is a more difficult question.

All but one of 31 economists polled by Reuters expect a rate hike this week, with most predicting the MPC will go 50basis points rather than 25, as it did in July and November.

When the rand tanked and bond yields soared after President Jacob Zuma fired Nhlanhla Nene as finance minister in December, some economists felt the Bank should call an emergency meeting to raise rates. It correctly held fire and avoided stoking the panic.

But the rand is no doubt going to be the biggest consideration in its "data dependent" decision this week. It is not just that the rand has not recovered from December’s savaging, but that the global environment has turned increasingly hostile to emerging markets. The combination has seen the rand tank.

It has lost more than 18% to the dollar since the MPC last met. Bank deputy governor Daniel Mminele noted in a recent speech that the rand had fallen 44% since the beginning of last year.

This is dire. Rand weakness will stoke inflation as its level is arguably one of the biggest influences on business people’s expectations of inflation and therefore on pricing. The Bank’s November forecast was for inflation to average 6% this year and to breach the top of the target range every now and again. That is definitely going to be raised.

Add to the rand’s sharp decline the costs of the drought, and the outlook for inflation is worse. With SA likely to import significant amounts of maize, the effect on food inflation is likely to be a lot greater than the Bank expected at its last meeting. Economists now have inflation going over 7% by the end of this year.

We have oil at below $30 on our side. But Mr Mminele has already indicated that the combined effect of the rand, the drought and higher electricity prices would outweigh any benefits of lower commodity prices.

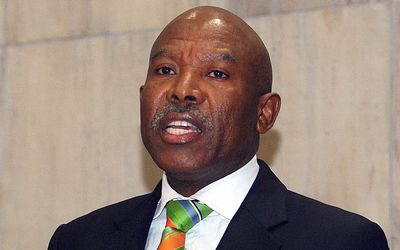

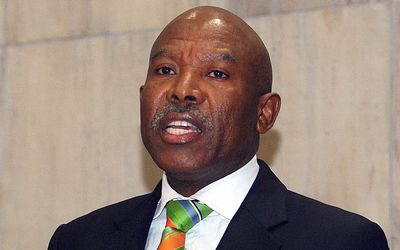

Governor Lesetja Kganyago made it clear last year that the Bank was uncomfortable with the degree to which inflationary expectations had got stuck at the top of the target range — allowing no scope for further shocks — and that the Bank had the appetite to take pre-emptive action to curb those expectations and prevent second-round effects on inflation.

That is what he and the MPC will have to do this week, despite SA’s weak growth trajectory — paradoxically, partly to protect what growth we have.

One of the biggest risks is the loss of policy credibility that could well see rating agencies downgrade SA to junk status. That could erode the rand, stoke inflationary pressures and undermine growth by robbing SA of foreign capital. Any competitiveness gains from a weaker exchange rate would be undermined by higher inflation and input costs.

If the Bank has said it would act proactively on inflation, it needs to do just that, and that indicates 50basis points rather than 25, given how much the outlook could deteriorate.

Which is not to say the inflation versus growth dilemma is not of concern. But as Mr Mminele has emphasised, monetary policy has only a limited role to play given the structural constraints to the economy.

South African Reserve Bank governor Lesetja Kganyago. Picture: PUXLEY MAKGATHO

LAST week, the International Monetary Fund cut its growth forecast for SA to 0.7% for this year.

The Reuters consensus forecast is now 0.9%, and some economists have taken theirs down to 0.2%.

At any other time, this might seem a moment for monetary policy to go slow on doing anything that might further undermine growth prospects. As it is, it is not a matter of whether the Reserve Bank’s monetary policy committee (MPC) will hike rates when it meets this week, but a matter of how much.

That’s because the way the world is going, and the position in which SA finds itself, there is surely no other option. By how much is a more difficult question.

All but one of 31 economists polled by Reuters expect a rate hike this week, with most predicting the MPC will go 50basis points rather than 25, as it did in July and November.

When the rand tanked and bond yields soared after President Jacob Zuma fired Nhlanhla Nene as finance minister in December, some economists felt the Bank should call an emergency meeting to raise rates. It correctly held fire and avoided stoking the panic.

But the rand is no doubt going to be the biggest consideration in its "data dependent" decision this week. It is not just that the rand has not recovered from December’s savaging, but that the global environment has turned increasingly hostile to emerging markets. The combination has seen the rand tank.

It has lost more than 18% to the dollar since the MPC last met. Bank deputy governor Daniel Mminele noted in a recent speech that the rand had fallen 44% since the beginning of last year.

This is dire. Rand weakness will stoke inflation as its level is arguably one of the biggest influences on business people’s expectations of inflation and therefore on pricing. The Bank’s November forecast was for inflation to average 6% this year and to breach the top of the target range every now and again. That is definitely going to be raised.

Add to the rand’s sharp decline the costs of the drought, and the outlook for inflation is worse. With SA likely to import significant amounts of maize, the effect on food inflation is likely to be a lot greater than the Bank expected at its last meeting. Economists now have inflation going over 7% by the end of this year.

We have oil at below $30 on our side. But Mr Mminele has already indicated that the combined effect of the rand, the drought and higher electricity prices would outweigh any benefits of lower commodity prices.

Governor Lesetja Kganyago made it clear last year that the Bank was uncomfortable with the degree to which inflationary expectations had got stuck at the top of the target range — allowing no scope for further shocks — and that the Bank had the appetite to take pre-emptive action to curb those expectations and prevent second-round effects on inflation.

That is what he and the MPC will have to do this week, despite SA’s weak growth trajectory — paradoxically, partly to protect what growth we have.

One of the biggest risks is the loss of policy credibility that could well see rating agencies downgrade SA to junk status. That could erode the rand, stoke inflationary pressures and undermine growth by robbing SA of foreign capital. Any competitiveness gains from a weaker exchange rate would be undermined by higher inflation and input costs.

If the Bank has said it would act proactively on inflation, it needs to do just that, and that indicates 50basis points rather than 25, given how much the outlook could deteriorate.

Which is not to say the inflation versus growth dilemma is not of concern. But as Mr Mminele has emphasised, monetary policy has only a limited role to play given the structural constraints to the economy.

Change: -0.47%

Change: -0.57%

Change: -1.76%

Change: -0.34%

Change: 0.02%

Data supplied by Profile Data

Change: -1.49%

Change: -0.01%

Change: -0.47%

Change: 0.00%

Change: -0.08%

Data supplied by Profile Data

Change: 0.61%

Change: 0.85%

Change: 0.20%

Change: -0.22%

Change: 0.82%

Data supplied by Profile Data

Change: 0.27%

Change: -0.42%

Change: 0.13%

Change: -1.22%

Change: -1.88%

Data supplied by Profile Data