PUT this in your pipe to smoke: Justin Bieber is as old as SA’s democracy. Make that 57 days older, born as he was on March 1, 1994. What can this mean? And specifically, what does this fact have to say for young people in SA who are just as old as he is, and who we might be finding on the ramparts in the student revolution, or what remains of it?

He could certainly stand for all that is wrong with whiteness, the picture of unfair privilege, poster child in the bubble wrap of white enclaves, the living spoof of western ignorance … not to speak of the Trump card in the argument, his hairstyle.

His South African student peers could add him to their new swear word, that year of 1994, which in their rhetoric has become something of an annus horribilis, when Nelson Mandela, now a rogue for many of their parents too, sold out the black economic revolution to white capital.

It has become commonplace to speak in derogatory terms of the 1994 narrative of reconciliation, which they say abandoned black socialism and prioritised racial harmony over racial justice. Even when struggle stalwarts patiently point out that Mandela took the courageous lead in taming what were still very destructive state forces, the neorevolutionaries remain unmoved.

Indeed, 1994 was an annus horribilis in many respects, not least for the 100 days of the Rwandan genocide, which coincided with the South African election. The fallout of the genocide dominated African politics for the next 15 years, preparing the ground for the continent’s own six-nation "world war", and eventually the Zimbabwean land grabs and the world’s most ambitious peace mission yet and state creation in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. An outbreak of the worst racism imaginable, the genocide’s lessons for our students are emphatic, as some of their own campaigns degenerate into ethnic scapegoating. The Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF), who have come close to hijacking #FeesMustFall, and the Hutu supremacists are all of a piece.

But the lesson should also be that our genocidal instincts can flourish anywhere; we were reminded all over again of the Holocaust, and that genocide was not just a function of technological overconfidence rooted in the misguided Enlightenment in Europe, but that it is also possible among the poorest of the poor armed with machetes only.

Those who claim that racism is confined to one race forget 1994 all too easily.

Talk racism and 1994 jumps out for the running news sensation of the decade: OJ Simpson’s killings of his wife Nicole and Ronald Goldman, followed by the most viewed car chase of all time. It was the year black America began striking back, when Rodney King was paid $3.2m for being beaten up by white cops. What the OJ Simpson trial later showed was that no longer was it only rich, white celebrity lawyers that could get rich, white criminals off the hook in the US: rich, black celebrity lawyers could return the compliment.

...

IT SHOWED how debilitating a discourse on racism can be, a wildfire that leaves nothing unscorched. Detective Mark Fuhrman entered the halls of infamy with his bloodied glove contaminating an open-and-shut case, much as latter-day white racists in SA poison anything they touch, from the constitutional rights of Afrikaans speakers to Neil Diamond impersonations (à la Hofmeyr).

It remains a travesty, though, that Furhman was the only figure in the trial to be prosecuted. It will always stand for its unrivalled demonstration on how to play the race card, and in SA the students with their obsession over whiteness have built a house of race cards that can go only one way.

For the rest, 1994 was an annus mirabilis. The last Russian troops left the Baltic states and East Germany, putting a full stop to the long afterword to 1945, the Cold War. Russia and the US pointed nuclear missiles away from each other with the Kremlin accords.

It was a good year for women’s rights. The Anglican Church ordained its first woman priests, Lorena Bobbit was let off the hook after cutting off the penis of her abusive husband, the US got its first female cadet at The Citadel military academy.

But the significance of 1994 for Bieber’s peers in SA is in the Rumpelstiltskin strides of globalisation. In January, China gained access to the internet. The Superhighway Summit presided over by then US vice-president Al Gore was held, as was the first conference devoted to the web’s commercial potential.

America Online gave ordinary Americans access to the web with the first search engine, Netscape Navigator. Many used that year’s new PowerPC microprocessors from Apple, an industry quantum leap.

The surge in global transport and appetite for dismantling borders, essential for globalisation, was heralded by the opening of the Channel Tunnel linking Paris and London. While it is probably true that the readiness for peace that swept the world in the 1990s played its part in Mandela’s ostensible compromise, what really changed SA and the world was the internet’s infiltration into everything. With it came an economic sea change with which we are still struggling to come to grips.

From 1994 onwards, the global village became a digital reality. Businesses hooked up, conducting operations in real time from all over the world. Money began flowing on a cosmic scale — soon the estimates would start hitting $3-trillion a day circling the world at electron speed. For US workers, the consequences were devastating, as was the North American Free Trade Agreement struck in 1994.

Decades of hard-fought labour rights that were already under siege, were now the excuse for Big Business to outsource jobs on a huge scale to the new constellation of special economic zones in China.

This is what really undermined SA’s revolution, this brave new world swamped by cheap western-designed products made in China, and the new world labour regime built on foundations laid by the Communist Party and its repression, leading to mass starvation and a Chinese survivalist work ethic under slave wages. Today it assiduously applies its own forms of apartheid — right down to passes and lokasies.

...

THEY were the new labour rivals in a global economy in which the internet allowed investment to be switched instantly from one country to another. The dispersal of the multinational corporations’ resources, personnel, and operations meant that the classic model of revolution, of the workers marching on the factory and seizing it, was no longer possible, or existed only in the fervid dreams of adolescents growing up on slogans in a liberation war that never was, as seems to be the case with the EFF.

Globalisation meant white capital became deracinated. In SA, it was no longer headquartered in Johannesburg; its global reincarnations turned their backs on any responsibility for apartheid restitution, complicity in it having been overridden in a freshly downloaded institutional memory. China declared it was fighting poverty in Africa by fighting it among its own subjects.

The internet also wired the world for exponential increases in the size of the derivatives industry. Risk could be sold down the global back alley several times, creating a boom world economy that in turn allowed companies to absorb SA’s affirmative action requirements. When the whole Potemkin village collapsed in 2008, a million of these quota employees were made redundant in SA overnight.

This is what the black born-frees discovered when they woke up and found their parents had failed to provide for their future, despite 21 years of managing the economy. All they had were cheap Chinese-made cellphones, PCs, and tablets that seduced them into believing they had kryptonite in their hands, like Superman.

Justin Bieber, the first internet superstar is above all the poster boy of its artifice. I remember how deeply offended I was when Vodacom, after a cellphone was foisted onto me, sent me a Justin Bieber CD as a bonus.

I could easily call it neocolonialist triumphalism. On a more intellectual level, his student peers are flying the flag of globalisation too — privilege theory, whiteness, intersectionality, just about every "new" concept in the debate comes from Anglo-American campuses, courtesy of the digital humanities.

That is the real lesson of 1994.

-

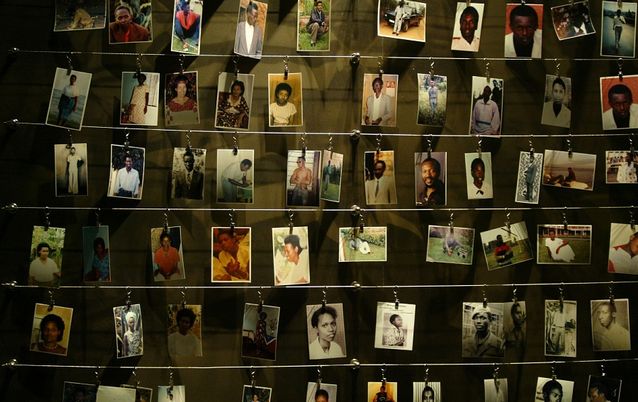

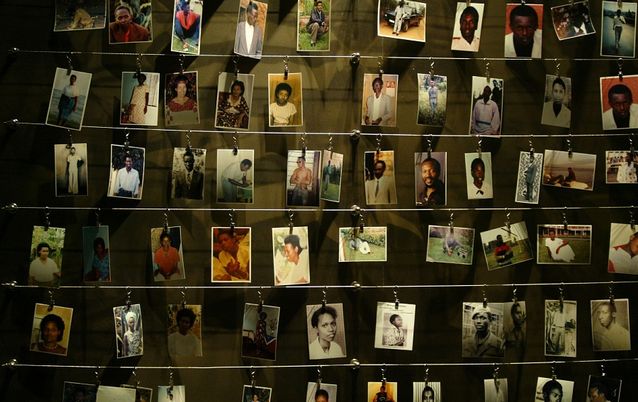

The year 1994 was notable for the coming of democracy to SA, the horrors of Rwanda, the opening of the Channel Tunnel and the killings committed by OJ Simpson. Picture: JUDA NGWENYA /REUTERS

-

OJ Simpson, wearing the blood stained gloves found by Los Angeles Police and entered into evidence in Simpson's murder trial, displays his hands to the jury at the request of prosecutor Christopher Darden in this file photograph from June 15, 1995. Picture: JUDA NGWENYA /REUTERS

-

Pictures of killed people donated by survivors are installed on a wall inside the Gisozi memorial in Kigali. Picture: REUTERS

-

The Eurostar express emerges on the French side after passing through the Channel tunnel at Sangatte. Picture: REUTERS

PUT this in your pipe to smoke: Justin Bieber is as old as SA’s democracy. Make that 57 days older, born as he was on March 1, 1994. What can this mean? And specifically, what does this fact have to say for young people in SA who are just as old as he is, and who we might be finding on the ramparts in the student revolution, or what remains of it?

He could certainly stand for all that is wrong with whiteness, the picture of unfair privilege, poster child in the bubble wrap of white enclaves, the living spoof of western ignorance … not to speak of the Trump card in the argument, his hairstyle.

His South African student peers could add him to their new swear word, that year of 1994, which in their rhetoric has become something of an annus horribilis, when Nelson Mandela, now a rogue for many of their parents too, sold out the black economic revolution to white capital.

It has become commonplace to speak in derogatory terms of the 1994 narrative of reconciliation, which they say abandoned black socialism and prioritised racial harmony over racial justice. Even when struggle stalwarts patiently point out that Mandela took the courageous lead in taming what were still very destructive state forces, the neorevolutionaries remain unmoved.

Indeed, 1994 was an annus horribilis in many respects, not least for the 100 days of the Rwandan genocide, which coincided with the South African election. The fallout of the genocide dominated African politics for the next 15 years, preparing the ground for the continent’s own six-nation "world war", and eventually the Zimbabwean land grabs and the world’s most ambitious peace mission yet and state creation in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. An outbreak of the worst racism imaginable, the genocide’s lessons for our students are emphatic, as some of their own campaigns degenerate into ethnic scapegoating. The Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF), who have come close to hijacking #FeesMustFall, and the Hutu supremacists are all of a piece.

But the lesson should also be that our genocidal instincts can flourish anywhere; we were reminded all over again of the Holocaust, and that genocide was not just a function of technological overconfidence rooted in the misguided Enlightenment in Europe, but that it is also possible among the poorest of the poor armed with machetes only.

Those who claim that racism is confined to one race forget 1994 all too easily.

Talk racism and 1994 jumps out for the running news sensation of the decade: OJ Simpson’s killings of his wife Nicole and Ronald Goldman, followed by the most viewed car chase of all time. It was the year black America began striking back, when Rodney King was paid $3.2m for being beaten up by white cops. What the OJ Simpson trial later showed was that no longer was it only rich, white celebrity lawyers that could get rich, white criminals off the hook in the US: rich, black celebrity lawyers could return the compliment.

...

IT SHOWED how debilitating a discourse on racism can be, a wildfire that leaves nothing unscorched. Detective Mark Fuhrman entered the halls of infamy with his bloodied glove contaminating an open-and-shut case, much as latter-day white racists in SA poison anything they touch, from the constitutional rights of Afrikaans speakers to Neil Diamond impersonations (à la Hofmeyr).

It remains a travesty, though, that Furhman was the only figure in the trial to be prosecuted. It will always stand for its unrivalled demonstration on how to play the race card, and in SA the students with their obsession over whiteness have built a house of race cards that can go only one way.

For the rest, 1994 was an annus mirabilis. The last Russian troops left the Baltic states and East Germany, putting a full stop to the long afterword to 1945, the Cold War. Russia and the US pointed nuclear missiles away from each other with the Kremlin accords.

It was a good year for women’s rights. The Anglican Church ordained its first woman priests, Lorena Bobbit was let off the hook after cutting off the penis of her abusive husband, the US got its first female cadet at The Citadel military academy.

But the significance of 1994 for Bieber’s peers in SA is in the Rumpelstiltskin strides of globalisation. In January, China gained access to the internet. The Superhighway Summit presided over by then US vice-president Al Gore was held, as was the first conference devoted to the web’s commercial potential.

America Online gave ordinary Americans access to the web with the first search engine, Netscape Navigator. Many used that year’s new PowerPC microprocessors from Apple, an industry quantum leap.

The surge in global transport and appetite for dismantling borders, essential for globalisation, was heralded by the opening of the Channel Tunnel linking Paris and London. While it is probably true that the readiness for peace that swept the world in the 1990s played its part in Mandela’s ostensible compromise, what really changed SA and the world was the internet’s infiltration into everything. With it came an economic sea change with which we are still struggling to come to grips.

From 1994 onwards, the global village became a digital reality. Businesses hooked up, conducting operations in real time from all over the world. Money began flowing on a cosmic scale — soon the estimates would start hitting $3-trillion a day circling the world at electron speed. For US workers, the consequences were devastating, as was the North American Free Trade Agreement struck in 1994.

Decades of hard-fought labour rights that were already under siege, were now the excuse for Big Business to outsource jobs on a huge scale to the new constellation of special economic zones in China.

This is what really undermined SA’s revolution, this brave new world swamped by cheap western-designed products made in China, and the new world labour regime built on foundations laid by the Communist Party and its repression, leading to mass starvation and a Chinese survivalist work ethic under slave wages. Today it assiduously applies its own forms of apartheid — right down to passes and lokasies.

...

THEY were the new labour rivals in a global economy in which the internet allowed investment to be switched instantly from one country to another. The dispersal of the multinational corporations’ resources, personnel, and operations meant that the classic model of revolution, of the workers marching on the factory and seizing it, was no longer possible, or existed only in the fervid dreams of adolescents growing up on slogans in a liberation war that never was, as seems to be the case with the EFF.

Globalisation meant white capital became deracinated. In SA, it was no longer headquartered in Johannesburg; its global reincarnations turned their backs on any responsibility for apartheid restitution, complicity in it having been overridden in a freshly downloaded institutional memory. China declared it was fighting poverty in Africa by fighting it among its own subjects.

The internet also wired the world for exponential increases in the size of the derivatives industry. Risk could be sold down the global back alley several times, creating a boom world economy that in turn allowed companies to absorb SA’s affirmative action requirements. When the whole Potemkin village collapsed in 2008, a million of these quota employees were made redundant in SA overnight.

This is what the black born-frees discovered when they woke up and found their parents had failed to provide for their future, despite 21 years of managing the economy. All they had were cheap Chinese-made cellphones, PCs, and tablets that seduced them into believing they had kryptonite in their hands, like Superman.

Justin Bieber, the first internet superstar is above all the poster boy of its artifice. I remember how deeply offended I was when Vodacom, after a cellphone was foisted onto me, sent me a Justin Bieber CD as a bonus.

I could easily call it neocolonialist triumphalism. On a more intellectual level, his student peers are flying the flag of globalisation too — privilege theory, whiteness, intersectionality, just about every "new" concept in the debate comes from Anglo-American campuses, courtesy of the digital humanities.

That is the real lesson of 1994.

Change: -1.27%

Change: -1.42%

Change: -1.87%

Change: -1.08%

Change: -2.01%

Data supplied by Profile Data

Change: -0.47%

Change: 0.61%

Change: -1.27%

Change: 0.00%

Change: 0.63%

Data supplied by Profile Data

Change: -0.12%

Change: -1.22%

Change: -0.17%

Change: 0.54%

Change: 0.00%

Data supplied by Profile Data

Change: -0.84%

Change: -1.85%

Change: -2.59%

Change: 0.36%

Change: -2.35%

Data supplied by Profile Data