AUTHOR INTERVIEW: Pitt plumbs depths of fading memory to free family’s secrets

by Sue Grant-Marshall,

2015-11-20 05:55:34.0

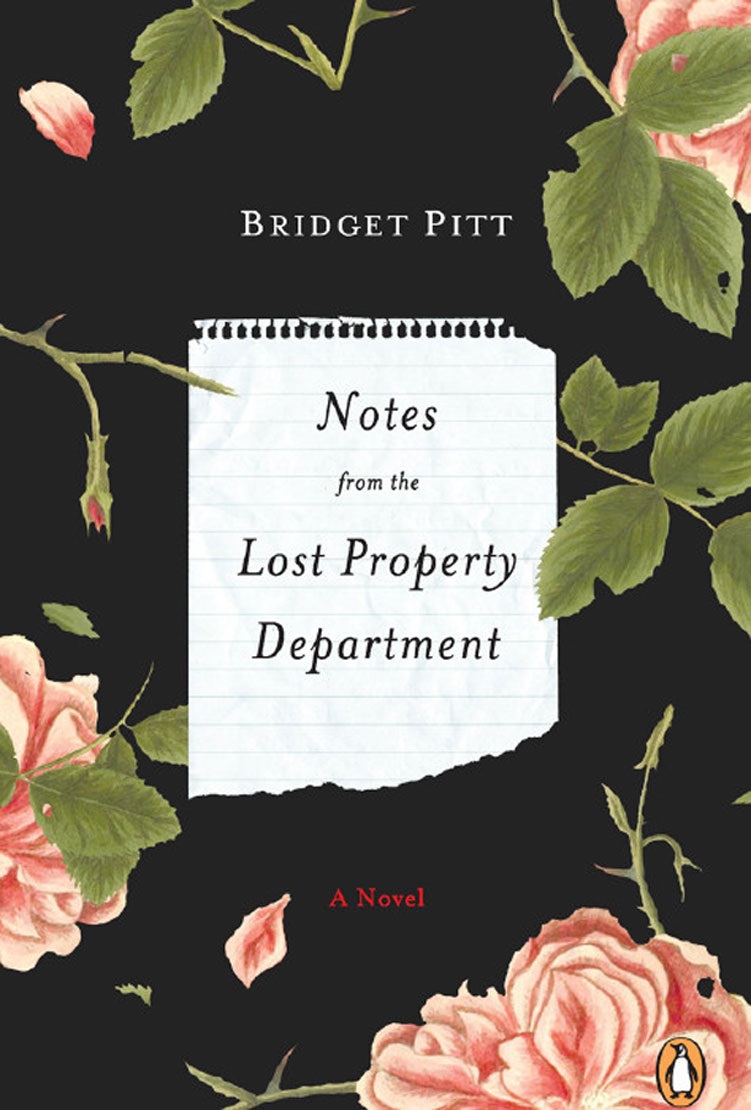

FAMILY secrets, parental guilt and the intricacies of memory fill this latest book from South African novelist Bridget Pitt, who continues to gather accolades for her work.

Principal protagonist Iris Langley is 11 years old when she plunges down a sheer cliff in the Drakensberg, sustaining severe brain damage. Her mother, Grace, falls too and suffers a stroke.

But the main action takes place many years later, in a retirement home. Iris, now a mother, rushes to Grace’s hospital bedside. There, she fights for Grace’s life the way her mother once fought to keep her from being institutionalised.

The story is told in two time spans and in the voices of Iris and Grace.

Grace home-schools Iris until the child has recovered enough of her brain faculties to return to the classroom and, eventually, to attend university. But she does not regain her memory of the day she fell. As Grace fades into dementia, Iris becomes convinced her mother is hiding a secret about the mountain accident.

Iris, once a sensitive child, has grown into an anxious, self-doubting adult whose life has been ruled by protective Grace’s decisions.

But with Iris’s fragmented memory and Grace’s once clear mind in tatters, the young woman ponders how she will ever find out what really happened on the day she fell.

As images flash tantalisingly in and out of her mind, Iris decides to jot down anything she can remember. In a role reversal well known to anyone who has had to mother their own mother, the increasingly confident Iris takes control of Grace’s life.

The contemporary narrative is set in Johannesburg. Pitt grew up in the city. She and her large family — she is one of five siblings — often travelled to holiday in the Drakensberg, climbing the chain ladder to the escarpment in the Amphitheatre region and staying at the Royal Natal National Park Hotel, where much of the novel’s action takes place.

Pitt has fictionalised several of her life’s experiences. Both her parents, Aubrey and Dodo Pitt, to whom she has dedicated this book, had falls in the Drakensberg. "And, both suffered from dementia, although for different reasons," she says.

Pitt has not based the young Iris’s manifestations of her brain damage on any particular case she studied when doing research for the book. "They were all so different, even with almost identical injuries. Iris is a composite."

How people recover, or don’t recover, is apparently highly individual, and in the 1970s, which is when young Iris falls, "they knew a lot less about the brain and were inclined to write you off. Now, they realise you can recover quite a lot of your faculties with the right stimulation and remedial assistance".

Pitt’s growing stature on the South African literary scene is well-deserved, for her characters are subtly and sensitively drawn.

Her fictional relationships — whether between an arrogant preteen and a shy, withdrawn one; once young lovers who meet again in middle age; or the often-tortured and precarious relationship between mothers and daughters — are unerringly portrayed.

Pitt, who was born in Zimbabwe, obtained her honours in psychology from the University of Cape Town before teaching in the early 1980s at schools on the Cape Flats.

"But I fell foul of the authorities, so I worked for the community newspaper, Grassroots, until 1987."

She was arrested several times due to her media work, her cartoons, the banners she painted for political and trade union marches, and the pamphlets she designed. At one stage, she had to go on the run in disguise. Some of those struggle-days experiences are fictionalised in her first book, Unbroken Wing, set in 1989 Cape Town.

Then followed a 12-year writing gap out of which emerged The Unseen Leopard, which was shortlisted for the Africa region of the 2011 Commonwealth Writers’ Prize, and shortlisted for the 2012 Wole Soyinka Prize for Literature in Africa.

A few months ago she was named runner-up in the 2015 Short Sharp Stories Awards, and also appears in a new book, Incredible Journey.

Bridget Pitt. Picture: SUPPLIED

FAMILY secrets, parental guilt and the intricacies of memory fill this latest book from South African novelist Bridget Pitt, who continues to gather accolades for her work.

Principal protagonist Iris Langley is 11 years old when she plunges down a sheer cliff in the Drakensberg, sustaining severe brain damage. Her mother, Grace, falls too and suffers a stroke.

But the main action takes place many years later, in a retirement home. Iris, now a mother, rushes to Grace’s hospital bedside. There, she fights for Grace’s life the way her mother once fought to keep her from being institutionalised.

The story is told in two time spans and in the voices of Iris and Grace.

Grace home-schools Iris until the child has recovered enough of her brain faculties to return to the classroom and, eventually, to attend university. But she does not regain her memory of the day she fell. As Grace fades into dementia, Iris becomes convinced her mother is hiding a secret about the mountain accident.

Iris, once a sensitive child, has grown into an anxious, self-doubting adult whose life has been ruled by protective Grace’s decisions.

But with Iris’s fragmented memory and Grace’s once clear mind in tatters, the young woman ponders how she will ever find out what really happened on the day she fell.

As images flash tantalisingly in and out of her mind, Iris decides to jot down anything she can remember. In a role reversal well known to anyone who has had to mother their own mother, the increasingly confident Iris takes control of Grace’s life.

The contemporary narrative is set in Johannesburg. Pitt grew up in the city. She and her large family — she is one of five siblings — often travelled to holiday in the Drakensberg, climbing the chain ladder to the escarpment in the Amphitheatre region and staying at the Royal Natal National Park Hotel, where much of the novel’s action takes place.

Pitt has fictionalised several of her life’s experiences. Both her parents, Aubrey and Dodo Pitt, to whom she has dedicated this book, had falls in the Drakensberg. "And, both suffered from dementia, although for different reasons," she says.

Pitt has not based the young Iris’s manifestations of her brain damage on any particular case she studied when doing research for the book. "They were all so different, even with almost identical injuries. Iris is a composite."

How people recover, or don’t recover, is apparently highly individual, and in the 1970s, which is when young Iris falls, "they knew a lot less about the brain and were inclined to write you off. Now, they realise you can recover quite a lot of your faculties with the right stimulation and remedial assistance".

Pitt’s growing stature on the South African literary scene is well-deserved, for her characters are subtly and sensitively drawn.

Her fictional relationships — whether between an arrogant preteen and a shy, withdrawn one; once young lovers who meet again in middle age; or the often-tortured and precarious relationship between mothers and daughters — are unerringly portrayed.

Pitt, who was born in Zimbabwe, obtained her honours in psychology from the University of Cape Town before teaching in the early 1980s at schools on the Cape Flats.

"But I fell foul of the authorities, so I worked for the community newspaper, Grassroots, until 1987."

She was arrested several times due to her media work, her cartoons, the banners she painted for political and trade union marches, and the pamphlets she designed. At one stage, she had to go on the run in disguise. Some of those struggle-days experiences are fictionalised in her first book, Unbroken Wing, set in 1989 Cape Town.

Then followed a 12-year writing gap out of which emerged The Unseen Leopard, which was shortlisted for the Africa region of the 2011 Commonwealth Writers’ Prize, and shortlisted for the 2012 Wole Soyinka Prize for Literature in Africa.

A few months ago she was named runner-up in the 2015 Short Sharp Stories Awards, and also appears in a new book, Incredible Journey.

Change: 1.37%

Change: 1.32%

Change: 2.91%

Change: 0.45%

Change: 3.09%

Data supplied by Profile Data

Change: 1.63%

Change: 0.83%

Change: 1.37%

Change: 0.00%

Change: 0.69%

Data supplied by Profile Data

Change: -2.04%

Change: -1.78%

Change: -1.55%

Change: -1.86%

Change: -1.48%

Data supplied by Profile Data

Change: -1.19%

Change: 0.31%

Change: -0.65%

Change: -1.39%

Change: 2.92%

Data supplied by Profile Data