HALF ART: Local windows on global significance

by Chris Thurman,

2016-03-04 05:57:25.0

THERE is a photograph pinned to the board in my office. It’s an image of a mine worker at the Serra Pelada, a now-defunct open-pit gold mine in Brazil. After a nugget of gold was found on an isolated farm in 1979, people rushed in their thousands to stake claims on the land — there had been nothing like it since the discovery of the Witwatersrand reef almost a century before.

A shanty town sprung up around what became a huge chasm in the earth. Nearby villages became notorious hubs of prostitution, booze and murder. Fortunes were made and lost. Basically, it was just like Johannesburg in the early days (some would say Joburg hasn’t changed much in the intervening century).

There, however, the similarities to SA end. The mine workers at the Serra Pelada worked under terrible conditions; they were subject to extortion by greedy entrepreneurs who hoarded basic goods to sell them at inflated prices; the state placed operations under the aegis of the Brazilian military; and environmental damage was severe.

Yet the place of the Serra Pelada in Brazil’s history is in no way comparable to the fundamental fusion of mining with SA’s economy and, consequently, with its race and class politics.

The mine worker stares down at me from my office wall, his clothing torn, his face and body caked with mud, smiling a Mona Lisa smile. His expression could be interpreted as optimistic, proud, stoical, cynical or any combination of these. There is something teasing in the photograph; it resists easy generalisations about individual agency or systemic oppression, about exploitation or resilient humanity.

The image was taken by Chilean artist Alfredo Jaar, and I first came across it in 2012, when it was displayed alongside an exhibition by SA’s photographic documenter-in-chief of mines, David Goldblatt. Now Jaar is back in SA, and a very different body of work can be viewed across two sites: The Sound of Silence at the Wits Art Museum and Amilcar, Frantz, Patrice and the Others at the Goodman Gallery Johannesburg.

If Jaar’s photographs of the Serra Pelada lured me into transnational comparisons, only to have these undermined by historical details, then the current exhibitions challenge South Africans again to consider the global circulation of images that seem to have "local" (place- and time specific) meanings. The Sound of Silence is a meditation on the famous photograph by Bang-Bang Club member Kevin Carter depicting a skeletal child apparently being stalked by a vulture during the famine in Sudan in 1993. Jaar’s film and installation try to get visitors to see the photo as if for the first time.

This Pulitzer Prize-winning image has become a standard reference point in debates about the ethics of photojournalism — the role of the photographer as participant-observer in situations of suffering, the value of shocking photos in raising awareness about important but often-neglected news stories, the commodification of such images in an age of voracious visual consumption, and so on.

Jaar faced similar ethical dilemmas with regard to the Rwandan genocide. While his critique emphasises the indifference shown towards Rwanda by western media and the deadly combination of meddling in and neglect of the conflict by European states in particular, South Africans are reminded that our own parochialism and exceptionalist self-congratulation in the wake of the first democratic elections led us, and our government, to an equally complicit negligence. This was a foreign policy failing of the Mandela era to which former president Thabo Mbeki’s African diplomatic efforts may be seen as an overcorrection.

Amilcar, Frantz, Patrice and the Others enters the South African scene while our country’s relation to the rest of the African continent remains contested. Although xenophobic attacks are a common occurrence, the African political thinkers and leaders that Jaar invokes — Cabral, Fanon, Lumumba — are a common feature of our political discourse.

And, of course, Nelson Mandela, to whom he also pays tribute, is increasingly being distanced from this "revolutionary" company.

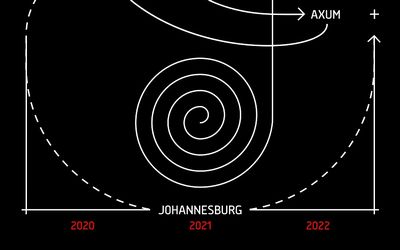

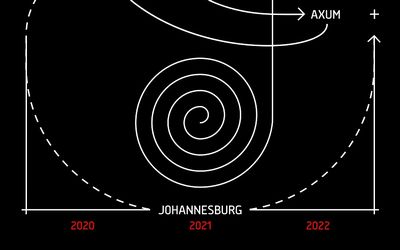

Johannesburg 2026 is part of the Alfredo Jaar exhibition, Amilcar, Frantz, Patrice and the Others, at the Goodman Gallery. Picture: SUPPLIED

THERE is a photograph pinned to the board in my office. It’s an image of a mine worker at the Serra Pelada, a now-defunct open-pit gold mine in Brazil. After a nugget of gold was found on an isolated farm in 1979, people rushed in their thousands to stake claims on the land — there had been nothing like it since the discovery of the Witwatersrand reef almost a century before.

A shanty town sprung up around what became a huge chasm in the earth. Nearby villages became notorious hubs of prostitution, booze and murder. Fortunes were made and lost. Basically, it was just like Johannesburg in the early days (some would say Joburg hasn’t changed much in the intervening century).

There, however, the similarities to SA end. The mine workers at the Serra Pelada worked under terrible conditions; they were subject to extortion by greedy entrepreneurs who hoarded basic goods to sell them at inflated prices; the state placed operations under the aegis of the Brazilian military; and environmental damage was severe.

Yet the place of the Serra Pelada in Brazil’s history is in no way comparable to the fundamental fusion of mining with SA’s economy and, consequently, with its race and class politics.

The mine worker stares down at me from my office wall, his clothing torn, his face and body caked with mud, smiling a Mona Lisa smile. His expression could be interpreted as optimistic, proud, stoical, cynical or any combination of these. There is something teasing in the photograph; it resists easy generalisations about individual agency or systemic oppression, about exploitation or resilient humanity.

The image was taken by Chilean artist Alfredo Jaar, and I first came across it in 2012, when it was displayed alongside an exhibition by SA’s photographic documenter-in-chief of mines, David Goldblatt. Now Jaar is back in SA, and a very different body of work can be viewed across two sites: The Sound of Silence at the Wits Art Museum and Amilcar, Frantz, Patrice and the Others at the Goodman Gallery Johannesburg.

If Jaar’s photographs of the Serra Pelada lured me into transnational comparisons, only to have these undermined by historical details, then the current exhibitions challenge South Africans again to consider the global circulation of images that seem to have "local" (place- and time specific) meanings. The Sound of Silence is a meditation on the famous photograph by Bang-Bang Club member Kevin Carter depicting a skeletal child apparently being stalked by a vulture during the famine in Sudan in 1993. Jaar’s film and installation try to get visitors to see the photo as if for the first time.

This Pulitzer Prize-winning image has become a standard reference point in debates about the ethics of photojournalism — the role of the photographer as participant-observer in situations of suffering, the value of shocking photos in raising awareness about important but often-neglected news stories, the commodification of such images in an age of voracious visual consumption, and so on.

Jaar faced similar ethical dilemmas with regard to the Rwandan genocide. While his critique emphasises the indifference shown towards Rwanda by western media and the deadly combination of meddling in and neglect of the conflict by European states in particular, South Africans are reminded that our own parochialism and exceptionalist self-congratulation in the wake of the first democratic elections led us, and our government, to an equally complicit negligence. This was a foreign policy failing of the Mandela era to which former president Thabo Mbeki’s African diplomatic efforts may be seen as an overcorrection.

Amilcar, Frantz, Patrice and the Others enters the South African scene while our country’s relation to the rest of the African continent remains contested. Although xenophobic attacks are a common occurrence, the African political thinkers and leaders that Jaar invokes — Cabral, Fanon, Lumumba — are a common feature of our political discourse.

And, of course, Nelson Mandela, to whom he also pays tribute, is increasingly being distanced from this "revolutionary" company.

Change: 1.19%

Change: 1.36%

Change: 2.19%

Change: 1.49%

Change: -0.77%

Data supplied by Profile Data

Change: -0.19%

Change: 0.69%

Change: 1.19%

Change: 0.00%

Change: 0.44%

Data supplied by Profile Data

Change: 0.62%

Change: 0.61%

Change: 0.23%

Change: 0.52%

Change: 0.12%

Data supplied by Profile Data

Change: -0.21%

Change: -1.22%

Change: -0.69%

Change: -0.51%

Change: 0.07%

Data supplied by Profile Data