HALF ART: Art of reflecting growing dissatisfaction

by Chris Thurman,

2015-12-18 06:01:03.0

AS I write, Jacob Zuma is the president of SA and Pravin Gordhan the minister of finance. Given recent events, it’s not impossible that by the time you read this column things will have changed again. But it’s unlikely. Although the dire consequences of Zuma’s Nhlanhla Nene-Desmond van Rooyen shuffle have yet to be fully felt, a measure of stability — albeit an unconvincing and temporary one — has returned.

This presents an opportunity to reflect on 2015, and particularly on the race and class dynamics of #RhodesMustFall, #FeesMustFall and, yes, even #ZumaMustFall. Dissatisfaction with the state of the nation after 20 years of nominal freedom, translating into anger at the African National Congress and the party political system that it has dominated, may well reach a tipping point next year. But so may frustration with the entrenched privilege of the whites and the wealthy in our unequal society.

Thus, while South Africans of various stripes find themselves in agreement over the incompetence, selfishness and malice of Jacob Zuma, there is very little common ground beyond that consensus.

It is not simply a matter of asking and answering: What is to be done? Some feel that change is best achieved through the ballot box; others, through the internal machinations of the ruling alliance; others, through Parliament and policy; others, through the Constitution and courts; others, through mass protest action. These means are not mutually exclusive.

Rather, the conflict can be understood in terms described by Caribbean-American writer and activist Audre Lorde: "There is no such thing as a single-issue struggle because we do not live single-issue lives." This is often cited in discussions of "intersectionality", to emphasise the ways in which social identities, and the challenges facing those who bear these identities, converge or diverge under changing circumstances.

Earlier this week, however, political commentator TO Molefe applied Lorde’s affirmation to a predicament that many people will face next year. When South Africans do take to the street en masse to vent their anger and bring about change — and when, hopefully, having had their first taste of protest action through #ZumaMustFall, white people join broad-based movements in which they make up a small demographic — compatriots will often share little beyond their immediate target.

"Single-issue struggles," Molefe wrote, "have you marching with someone who has separate enamel crockery for your mother, who’s barred from eating from the family dishware she cleans even though she’s apparently just like family." It’s an extreme example, but the point applies in untold more subtle instances where race, class and gender nuances may be elided for the sake of a common battle. We ignore such elision at our peril.

And what of South African artists? Art can neither be constrained by, nor can it ever entirely escape, the historical conditions under which it is produced. Next year I expect plenty of explicit critique — more scathing depictions of Zuma that will force us to confront the ugly truth of the man and of the party that gave him such sway. Yet rage and despair are often sublimated in works of art; a painting of a baobab tree can be suffused with the tragedy of the miners shot down at Marikana.

The key lies in what we as viewers make of such works. Two exhibitions running in Johannesburg demonstrate this point neatly.

At the Goodman Gallery, the drawings in ruby onyinyechi amanze’s Salt and Water insist, both in their media (she uses a combination of graphite, ink, enamel, paper collage, photo transfers and pencil) and in their subjects (curious hybrid characters who share the page but hardly seem to be connected), on the "absurdity", the inevitability and indeed the necessity of the kind of "co-existence" observed by Molefe.

Meanwhile, Room Gallery’s new premises in Doornfontein are dedicated to the continuation of The Bright Night Project, which aims to raise awareness about the solar powered lamps distributed by the Little Sun initiative. The art works are a means to a practical end: the promotion of an inclusive social business (not a charity). There is a balance here of optimism and pragmatism, both of which will be sorely needed next year.

• Goodman Gallery, 10 Chester Rd, Johannesburg; Room Gallery, 23 Voorhout St, Johannesburg.

-

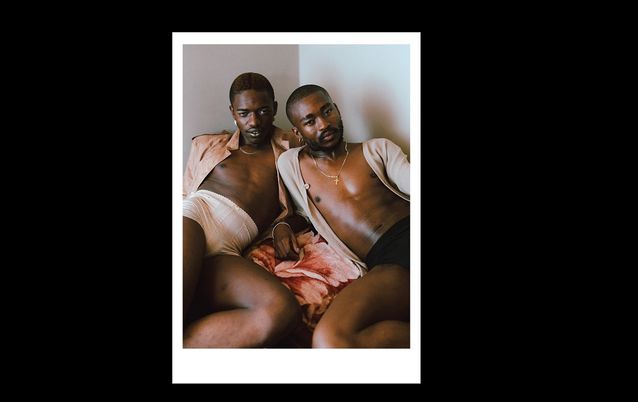

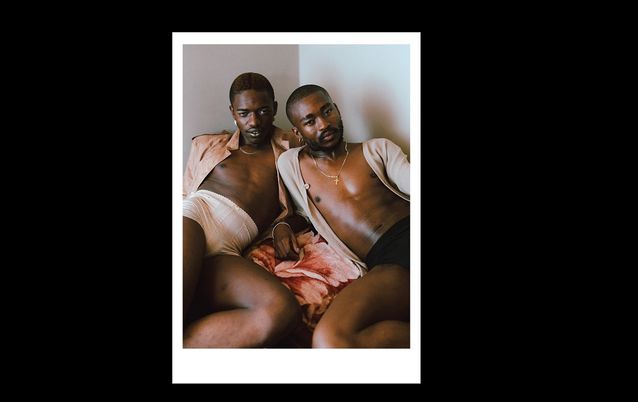

Desire Marea & Fela Gucci (FAKA) (detail). Kristin-Lee Moolman. Picture: SUPPLIED

-

Enlightened (detail). Karabo Poppy Moletsane. Picture: SUPPLIED

-

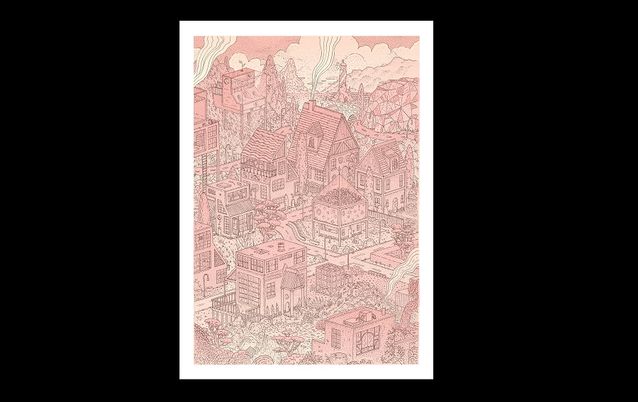

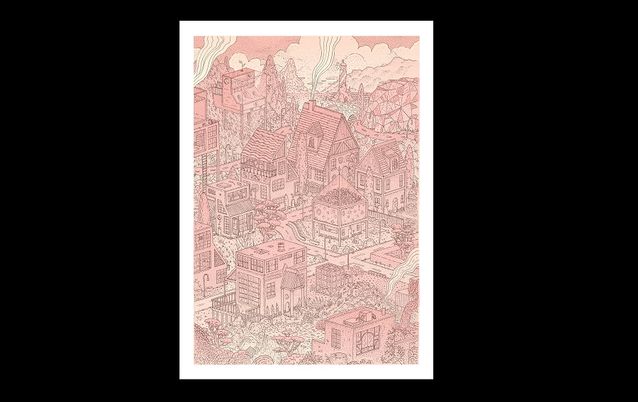

Twilight Town (detail). Jean de Wet. Picture: SUPPLIED

-

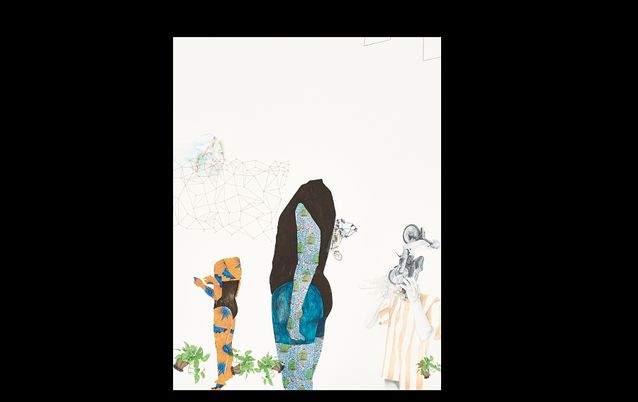

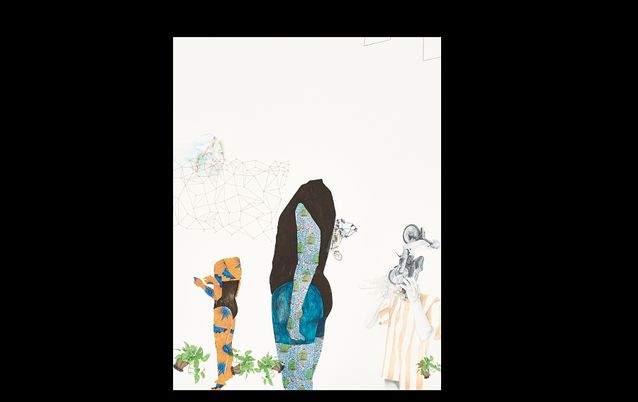

The Way You Think is Like a Wing, 2015 (detail). ruby onyinyechi amanze. Graphite, ink, photo transfers and metallic enamel 127 x 96.52cm. Picture: SUPPLIED

-

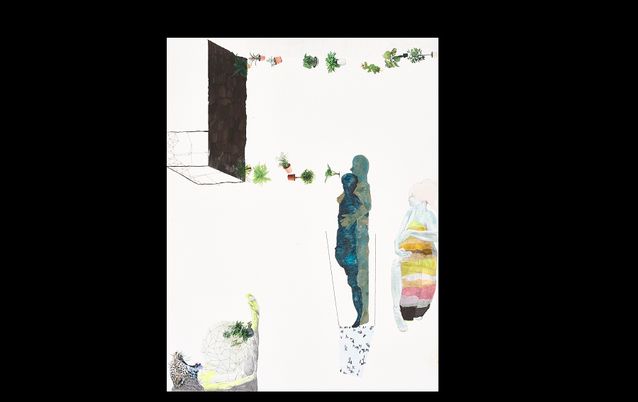

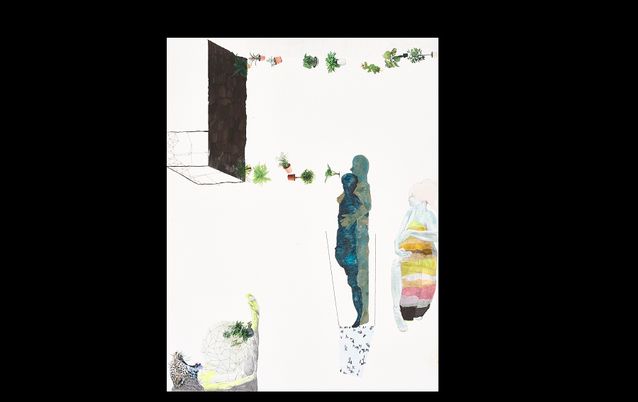

The Weight of Nothing [even plants fly], 2015 (detail). ruby onyinyechi amanze. Graphite, ink, photo transfers and colored pencils 96.52 x 127cm . Picture: SUPPLIED

AS I write, Jacob Zuma is the president of SA and Pravin Gordhan the minister of finance. Given recent events, it’s not impossible that by the time you read this column things will have changed again. But it’s unlikely. Although the dire consequences of Zuma’s Nhlanhla Nene-Desmond van Rooyen shuffle have yet to be fully felt, a measure of stability — albeit an unconvincing and temporary one — has returned.

This presents an opportunity to reflect on 2015, and particularly on the race and class dynamics of #RhodesMustFall, #FeesMustFall and, yes, even #ZumaMustFall. Dissatisfaction with the state of the nation after 20 years of nominal freedom, translating into anger at the African National Congress and the party political system that it has dominated, may well reach a tipping point next year. But so may frustration with the entrenched privilege of the whites and the wealthy in our unequal society.

Thus, while South Africans of various stripes find themselves in agreement over the incompetence, selfishness and malice of Jacob Zuma, there is very little common ground beyond that consensus.

It is not simply a matter of asking and answering: What is to be done? Some feel that change is best achieved through the ballot box; others, through the internal machinations of the ruling alliance; others, through Parliament and policy; others, through the Constitution and courts; others, through mass protest action. These means are not mutually exclusive.

Rather, the conflict can be understood in terms described by Caribbean-American writer and activist Audre Lorde: "There is no such thing as a single-issue struggle because we do not live single-issue lives." This is often cited in discussions of "intersectionality", to emphasise the ways in which social identities, and the challenges facing those who bear these identities, converge or diverge under changing circumstances.

Earlier this week, however, political commentator TO Molefe applied Lorde’s affirmation to a predicament that many people will face next year. When South Africans do take to the street en masse to vent their anger and bring about change — and when, hopefully, having had their first taste of protest action through #ZumaMustFall, white people join broad-based movements in which they make up a small demographic — compatriots will often share little beyond their immediate target.

"Single-issue struggles," Molefe wrote, "have you marching with someone who has separate enamel crockery for your mother, who’s barred from eating from the family dishware she cleans even though she’s apparently just like family." It’s an extreme example, but the point applies in untold more subtle instances where race, class and gender nuances may be elided for the sake of a common battle. We ignore such elision at our peril.

And what of South African artists? Art can neither be constrained by, nor can it ever entirely escape, the historical conditions under which it is produced. Next year I expect plenty of explicit critique — more scathing depictions of Zuma that will force us to confront the ugly truth of the man and of the party that gave him such sway. Yet rage and despair are often sublimated in works of art; a painting of a baobab tree can be suffused with the tragedy of the miners shot down at Marikana.

The key lies in what we as viewers make of such works. Two exhibitions running in Johannesburg demonstrate this point neatly.

At the Goodman Gallery, the drawings in ruby onyinyechi amanze’s Salt and Water insist, both in their media (she uses a combination of graphite, ink, enamel, paper collage, photo transfers and pencil) and in their subjects (curious hybrid characters who share the page but hardly seem to be connected), on the "absurdity", the inevitability and indeed the necessity of the kind of "co-existence" observed by Molefe.

Meanwhile, Room Gallery’s new premises in Doornfontein are dedicated to the continuation of The Bright Night Project, which aims to raise awareness about the solar powered lamps distributed by the Little Sun initiative. The art works are a means to a practical end: the promotion of an inclusive social business (not a charity). There is a balance here of optimism and pragmatism, both of which will be sorely needed next year.

• Goodman Gallery, 10 Chester Rd, Johannesburg; Room Gallery, 23 Voorhout St, Johannesburg.

Change: -0.07%

Change: -0.13%

Change: -1.59%

Change: 0.00%

Change: 1.05%

Data supplied by Profile Data

Change: -0.40%

Change: -0.98%

Change: -0.07%

Change: 0.00%

Change: -1.20%

Data supplied by Profile Data

Change: -0.01%

Change: -0.03%

Change: -0.05%

Change: -0.07%

Change: 0.00%

Data supplied by Profile Data

Change: 0.00%

Change: 0.21%

Change: -0.07%

Change: 0.19%

Change: 0.08%

Data supplied by Profile Data