THE cumulative science of HIV/ AIDS stands or falls independently of former president Thabo Mbeki’s — or any other individual’s — views or opinions on what causes what in the natural world.

Medical science is indifferent to individual views on the science of what causes disease. What is important to medical research are laboratory, clinical and community epidemiological observations.

When it comes to HIV/AIDS, the facts could not be clearer, as stated in one of the best scientific texts on the subject (Viruses and Human Disease, 2002, page 196) co-authored by the California Institute of Technology’s James and Ellen Strauss.

They write: "Two human lentiviruses, HIV-1 and HIV-2, cause the well-known disease called AIDS (acquired immune-deficiency syndrome).

"Although both HIV-1 and HIV-2 cause AIDS in people, HIV-2 is not as serious a pathogen. It is HIV-1 that is responsible for the vast majority of AIDS in people, and HIV-1 has correspondingly been much more exhaustively studied."

This summary of a conclusion reached in the mid-1990s, when Mbeki was former president Nelson Mandela’s deputy, is the basis of all developments on the treatment side of HIV/AIDS — advances in antiretroviral (ARV) and gene-replacement therapies — and on the preventive side — preparations are being made to test a promising candidate prevaccine in SA as we speak.

The biological fact that HIV causes AIDS is incontrovertible. If further proof is required, specifically that a virus such as HIV is able to cause a syndrome such as AIDS, here is one of our distinguished world-class experts, Dr Salim Abdool Karim: "The fact is that viruses can and do cause syndromes.

"The chickenpox virus causes Ramsay Hunt syndrome, an ear-canal rash with facial neuropathy. Middle East Respiratory Syndrome is caused by the MERS corona-virus. Slapped cheek syndrome is caused by parvo-virus B19."

The case, as they say, is closed. Why then does Mbeki persist where others would cringe in embarrassment?

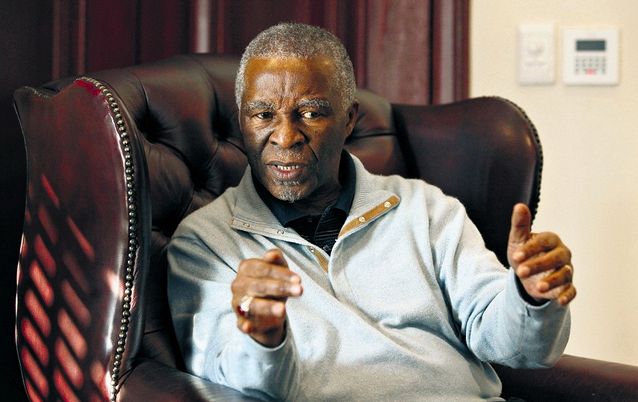

Mbeki is no ordinary citizen, but was the country’s president when our HIV/AIDS epidemic spun out of control.

His and the late former health minister Manto Tshabalala-Msimang’s confused thinking and policy paralysis resulted, as the highly regarded Harvard University study estimated, in the premature deaths of 330,000 people.

Mbeki is the villain in this piece. The heroes were the Treatment Action Campaign, with its unremitting activism, the Constitutional Court’s ARV roll-out order, former health minister Barbara Hogan, who set policy right in September 2008, and individuals such as Dr Fareed Abdullah, who ran the Western Cape’s ARV programme in utter defiance of the "garlic and beetroot" approach of Tshabalala-Msimang.

Mbeki and Tshabalala-Msimang’s paralysis also left the staggering legacy of our health system having to support, as we must, the 6.8-million individuals living with HIV/AIDS as of 2014, that the country’s health and medical community, under the leadership of Health Minister Aaron Motsoaledi, keep on ARV treatment.

Understanding why Mbeki failed to take the right course of action matters, if only to set up a balanced relationship between the world of science and responsible public policy-making.

While judgment matters in the final analysis, policy makers cannot get away with going against proven scientific argument without good reason and, whichever way one looks at it, Mbeki’s thinking is plain wrong.

So, what’s up?

A simple reason may be that he cannot own up to his mistakes. He has not explained nor apologised for keeping Zimbabwe’s President Robert Mugabe in power, nor for his mistaken views on HIV/AIDS.

Indeed, Mbeki flummoxed everyone by restating the denialism, conferring a self-inflicted wound on his dubious legacy.

Another possible reason is that Mbeki is trained in social science, not science, and there are huge differences in how these fields of inquiry deal with the concepts of "theory" and "cause".

In social science, a theory is a group of hypotheses. In science, a theory is a body of proven fact. In social science, a cause is the measurement of social action in an uncontrolled environment.

In biological science, a cause is a laboratory-based observable measurement of biochemical actions in a controlled environment. As a result, the degree of certainty varies considerably between the one epistemology and the other.

Mbeki clearly — and deliberately — confused the two.

But the real reason for Mbeki’s folly is poor judgment.

Beyond Zimbabwe and HIV/AIDS, Mbeki’s narcissism and poor power play in an organisation he knew very well — the African National Congress (ANC) — resulted in Jacob Zuma, someone who originally had no ambition to become president, rising to become Number One.

Like many other overcontrolling leaders, he tried to orchestrate a succession in an environment he could not perforce control, an environment that was democratic and not Marxist-Leninist.

Mbeki had forgotten he was no longer in exile, no longer the chief strategist of a liberation movement, no longer someone who could get things done by pulling strings, no longer someone who could operate inscrutably and no longer someone who did not have to contend with democratic checks and balances.

Perhaps, most important of all, he no longer was someone whose moral community consisted only of ANC cadres but, instead, the South African nation as whole.

One sees the same phenomenon with the current president, Zuma — that sad, enduring inability to see the nation as a moral community in its full wholesomeness.

But it would be wrong to reduce the problem to an individual.

Mbeki and Zuma are symptoms of the deeper institutional malaise of the ANC’s inability to become a modern political party with a forward-looking vision that serves the full moral community of South Africans by taking responsible decisions in the national, and not the party’s, interests.

The great Oxford biographer Gitta Sereny once wrote (Into that Darkness, page 367) that: "Social morality is contingent upon the individual’s capacity to make responsible decisions, to make the fundamental choice between right and wrong."

This capacity, she notes, emerges when we begin to be in charge of and increasingly responsible for our actions, a quality that best develops under circumstances of freedom, not oppression.

The deepest problem of the ANC is that it never grounded this moral quality that the revered Mandela had in such extraordinary abundance, in the heart and soul of its institutions.

Instead, we have Mbeki and Zuma, individuals who are unmoved by social morality, but instead do things when they are compelled to by law or by the narrow political forces that matter to them.

• Dr James is health spokesperson for the Democratic Alliance and honorary professor in the division of human genetics at the University of Cape Town’s Medical School.

Change: 1.19%

Change: 1.36%

Change: 2.19%

Change: 1.49%

Change: -0.77%

Data supplied by Profile Data

Change: -0.19%

Change: 0.69%

Change: 1.19%

Change: 0.00%

Change: 0.44%

Data supplied by Profile Data

Change: 0.62%

Change: 0.61%

Change: 0.23%

Change: 0.52%

Change: 0.12%

Data supplied by Profile Data

Change: -0.21%

Change: -1.22%

Change: -0.69%

Change: -0.51%

Change: 0.07%

Data supplied by Profile Data