THE institution of a national minimum wage in SA has the potential to raise the incomes of the poor, reduce inequality, and boost domestic spending, consumption, output and growth — all without a significant effect on employment.

This is international experience and the results of the most appropriate statistical modelling exercise undertaken to date. It is not the position advanced by Nicoli Nattrass and Jeremy Seekings in their Business Day article of December 8.

It would be impossible to deny that companies face cost constraints and that a national minimum wage set at a decent level would raise wage costs, while having various beneficial effects. Equally, it is implausible to conclude, as Nattrass and Seekings repeatedly do, that boosting domestic demand has no role to play in generating growth in the economy.

They rely on the results of the Treasury’s computable general equilibrium model, which shows that even a minimum wage set at an amount lower than many existing minima would lead to catastrophe for the economy. This is not surprising. The model is designed in such a way that this is the only outcome possible. The architecture is such that almost any "friction" in the labour market (such as "artificially" raising wages through instituting minimum wages) will result in the economy automatically "substituting" away from labour and employment falling. The model is "supply-side" driven, with prices — including the cost of labour — playing a determining role.

In the model, investment is equal to savings, with no meaningful depiction of the financial sector or real corporate behaviour, and corporate savings presumably fall when wages increase. It appears that increased spending in the model is automatically skewed towards imports and not domestic demand. There is no room for increased demand to play a substantive role in stimulating the domestic economy.

The results of the Treasury’s model include significant harm at a national minimum wage of a shamefully low R1,258 a month (a 0.8%, or 90,000, drop in employment in the short term and 1% lower gross domestic product, or GDP, in the long term), disaster at R1,886 (a fall of 2.1%, or around 250,000, in employment and 2.5% in GDP) and catastrophe at R4,303 (employment plummeting by 10.1%, or about 1.4-million, and GDP sliding 13%).

Tellingly, a similar computable general equilibrium model predicted that a youth wage subsidy — effectively a reduction in the cost of labour — would boost employment 2%-10%. Thus far, the youth wage subsidy instituted at the start of last year has had zero positive impact.

The claim by Nattrass and Seekings that SA is "profit-led" and not "wage-led" is selective and overly simplified. The cited studies, which use an extremely simplistic model not at all customised for SA, show that domestic demand in SA is "wage-led", but overall demand is not. What "profit-led" means is that the benefits in consumption from increased wages — those do exist — are outweighed by the decline in investment from profits and shifts in net imports and exports. But profit-led regimes are dysfunctional, as the same authors note: "growth has nowhere been based on a profit-led growth process.

IT IS a well-established fact that the poor consume a higher proportion of their wages. The "profit-led" finding is in part based on this being less true for SA. However, looking only at the post-apartheid period (the model runs until 2004), the findings change and consumption by the poor becomes much more important. The high propensity to import may be driven in significant part by luxury goods for the rich. None of these factors are explored in any depth.

More recent analysis, exploring the same relationships and using the United Nations Global Policy Model, shows that a rising wage share in SA would be good for growth. This model is far more sophisticated and, unlike the one cited by Nattrass and Seekings, is used for forecasting by the Group of 20.

This is congruent with a 2015 International Monetary Fund study that shows that higher wages for the poor spur growth, while increasing income for the richest hurts growth.

The modelling undertaken by Wits University’s National Minimum Wage Research Initiative on the effect of a national minimum wage is also rejected out of hand by Nattrass and Seekings. This modelling relies on detailed analysis of the past relations of the South African economy.

Unlike the computable general equilibrium model, it includes dynamic interaction between supply and demand factors in the economy, allowing for the possibility that increases to domestic demand may compensate for higher input costs.

The results, most tellingly, are in line with international and domestic experience, showing reductions in poverty and inequality and aggregate benign employment effects. The results Nattrass and Seekings cite are in line with the doom-and-gloom prophesies that have been made by conservative scholars and business pundits around the world before the implementation of a national minimum wage that have systematically been proved false.

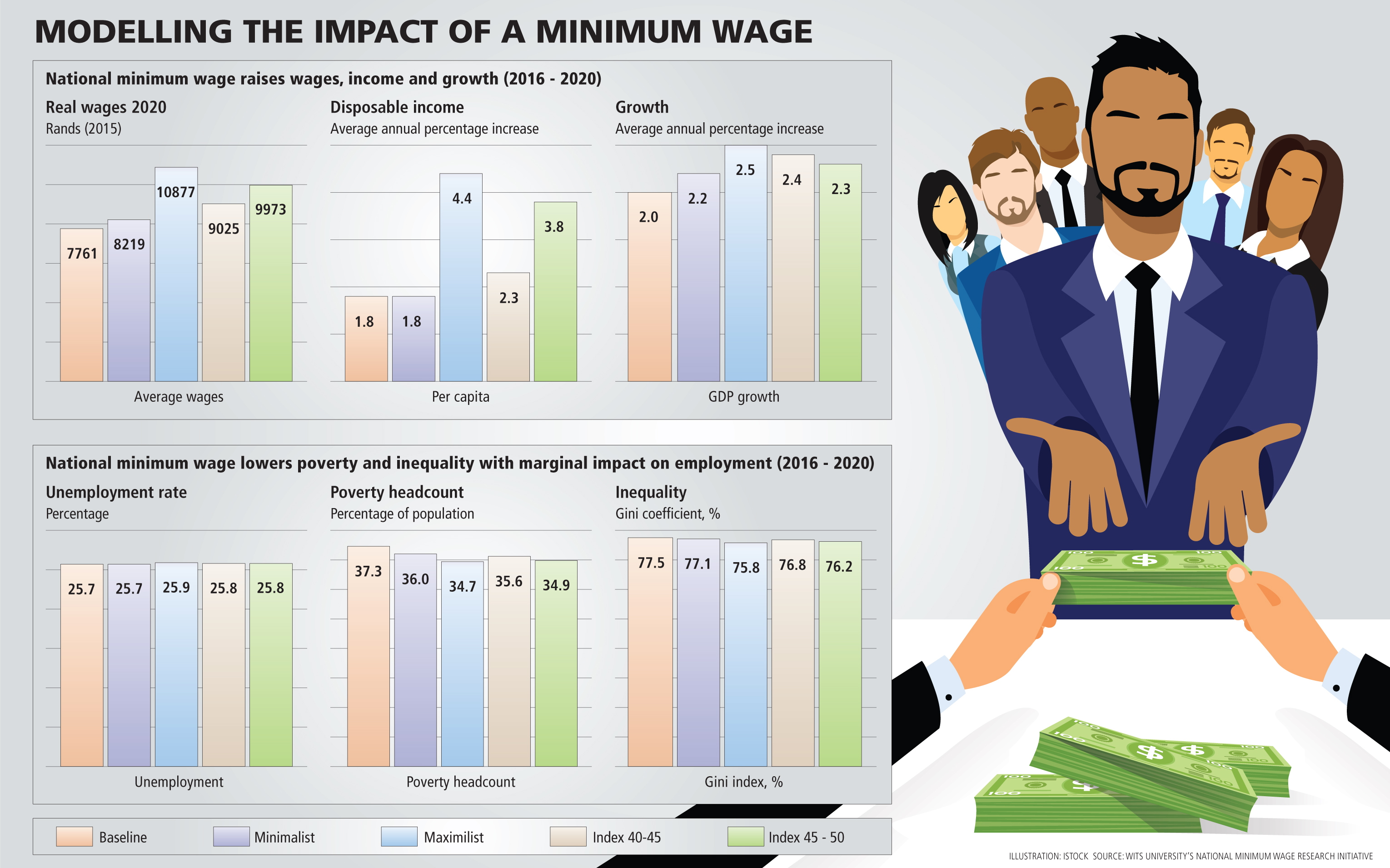

The five scenarios modelled by Wits — of increases of between R2,250 (the "minimalist" scenario) and R6,000 (the "maximalist" scenario) show estimates for 2016-2020.

Indexation scenarios refer to tying the national minimum wage to a gradually increasing percentage of the average wage over five years: "index 40%-45%" moves from approximately R3,500 to R3,900 and "index 45%-50%" from approximately R4,600 to R5,100 (in 2014 rand).

Average real wages for full-time employees are higher than the baseline "business as usual" scenario in the other four scenarios. They rise by a maximum of 28% to R10,877 in the maximalist scenario by 2020.

Wage increases disproportionately benefit the poorest. This leads to a rise in disposable income and an increase in household spending. Once again, the indexation scenarios fall between the minimalist and maximalist positions.

THE rise in incomes stimulates growth through increased spending. Real GDP growth in the baseline scenario averages at only 2%, but rises to 2.2%-2.5% with the institution of a national minimum wage. Stimulating output and growth in the economy in five years can have long-lasting effects in changing the trajectory of the economy in the long term.

In all the scenarios, the number of people employed increases, while the unemployment rate rises marginally above the baseline, by a maximum of 0.2% — assuming that nothing else is done to make the growth path more "jobs rich".

This very slight increase in the unemployment rate fits the pattern observed internationally. It is a minor trade-off when considering the positive growth effects.

Unsurprisingly, and again in line with the international experience, we see a drop in poverty and inequality in all scenarios. The percentage of the population defined as poor is as much as 2.6 percentage points lower than the 37.3% in the baseline scenario.

We should recall that income disparity (and not unemployment) is the main driver of inequality. Minimum wages have been shown to also push up wages for those earning close to, but above the minimum, so the effect on inequality is likely to be greater than shown.

Finally, there is scant empirical evidence, and none offered by Nattrass and Seekings, that low wages will assist SA in boosting growth and reducing poverty, inequality and unemployment. The persistence of low real wages and rising unemployment in the past two decades suggests the opposite.

The national minimum was promised by the government and the ANC, if set at a level above the current (often low) sectoral minima, has the potential to reduce inequality and poverty and boost growth in the economy.

Do we need to be prudent in the design of a national minimum wage? Yes. Are the doom-and-gloom predictions of Nattrass and Seekings credible? No.

• Isaacs is the co-ordinator of the National Minimum Wage Research Initiative at Corporate Strategy and Industrial Development, in the school of economics and business sciences at the University of the Witwatersrand.

Picture: THINKSTOCK

THE institution of a national minimum wage in SA has the potential to raise the incomes of the poor, reduce inequality, and boost domestic spending, consumption, output and growth — all without a significant effect on employment.

This is international experience and the results of the most appropriate statistical modelling exercise undertaken to date. It is not the position advanced by Nicoli Nattrass and Jeremy Seekings in their Business Day article of December 8.

It would be impossible to deny that companies face cost constraints and that a national minimum wage set at a decent level would raise wage costs, while having various beneficial effects. Equally, it is implausible to conclude, as Nattrass and Seekings repeatedly do, that boosting domestic demand has no role to play in generating growth in the economy.

They rely on the results of the Treasury’s computable general equilibrium model, which shows that even a minimum wage set at an amount lower than many existing minima would lead to catastrophe for the economy. This is not surprising. The model is designed in such a way that this is the only outcome possible. The architecture is such that almost any "friction" in the labour market (such as "artificially" raising wages through instituting minimum wages) will result in the economy automatically "substituting" away from labour and employment falling. The model is "supply-side" driven, with prices — including the cost of labour — playing a determining role.

In the model, investment is equal to savings, with no meaningful depiction of the financial sector or real corporate behaviour, and corporate savings presumably fall when wages increase. It appears that increased spending in the model is automatically skewed towards imports and not domestic demand. There is no room for increased demand to play a substantive role in stimulating the domestic economy.

The results of the Treasury’s model include significant harm at a national minimum wage of a shamefully low R1,258 a month (a 0.8%, or 90,000, drop in employment in the short term and 1% lower gross domestic product, or GDP, in the long term), disaster at R1,886 (a fall of 2.1%, or around 250,000, in employment and 2.5% in GDP) and catastrophe at R4,303 (employment plummeting by 10.1%, or about 1.4-million, and GDP sliding 13%).

Tellingly, a similar computable general equilibrium model predicted that a youth wage subsidy — effectively a reduction in the cost of labour — would boost employment 2%-10%. Thus far, the youth wage subsidy instituted at the start of last year has had zero positive impact.

The claim by Nattrass and Seekings that SA is "profit-led" and not "wage-led" is selective and overly simplified. The cited studies, which use an extremely simplistic model not at all customised for SA, show that domestic demand in SA is "wage-led", but overall demand is not. What "profit-led" means is that the benefits in consumption from increased wages — those do exist — are outweighed by the decline in investment from profits and shifts in net imports and exports. But profit-led regimes are dysfunctional, as the same authors note: "growth has nowhere been based on a profit-led growth process.

IT IS a well-established fact that the poor consume a higher proportion of their wages. The "profit-led" finding is in part based on this being less true for SA. However, looking only at the post-apartheid period (the model runs until 2004), the findings change and consumption by the poor becomes much more important. The high propensity to import may be driven in significant part by luxury goods for the rich. None of these factors are explored in any depth.

More recent analysis, exploring the same relationships and using the United Nations Global Policy Model, shows that a rising wage share in SA would be good for growth. This model is far more sophisticated and, unlike the one cited by Nattrass and Seekings, is used for forecasting by the Group of 20.

This is congruent with a 2015 International Monetary Fund study that shows that higher wages for the poor spur growth, while increasing income for the richest hurts growth.

The modelling undertaken by Wits University’s National Minimum Wage Research Initiative on the effect of a national minimum wage is also rejected out of hand by Nattrass and Seekings. This modelling relies on detailed analysis of the past relations of the South African economy.

Unlike the computable general equilibrium model, it includes dynamic interaction between supply and demand factors in the economy, allowing for the possibility that increases to domestic demand may compensate for higher input costs.

The results, most tellingly, are in line with international and domestic experience, showing reductions in poverty and inequality and aggregate benign employment effects. The results Nattrass and Seekings cite are in line with the doom-and-gloom prophesies that have been made by conservative scholars and business pundits around the world before the implementation of a national minimum wage that have systematically been proved false.

The five scenarios modelled by Wits — of increases of between R2,250 (the "minimalist" scenario) and R6,000 (the "maximalist" scenario) show estimates for 2016-2020.

Indexation scenarios refer to tying the national minimum wage to a gradually increasing percentage of the average wage over five years: "index 40%-45%" moves from approximately R3,500 to R3,900 and "index 45%-50%" from approximately R4,600 to R5,100 (in 2014 rand).

Average real wages for full-time employees are higher than the baseline "business as usual" scenario in the other four scenarios. They rise by a maximum of 28% to R10,877 in the maximalist scenario by 2020.

Wage increases disproportionately benefit the poorest. This leads to a rise in disposable income and an increase in household spending. Once again, the indexation scenarios fall between the minimalist and maximalist positions.

THE rise in incomes stimulates growth through increased spending. Real GDP growth in the baseline scenario averages at only 2%, but rises to 2.2%-2.5% with the institution of a national minimum wage. Stimulating output and growth in the economy in five years can have long-lasting effects in changing the trajectory of the economy in the long term.

In all the scenarios, the number of people employed increases, while the unemployment rate rises marginally above the baseline, by a maximum of 0.2% — assuming that nothing else is done to make the growth path more "jobs rich".

This very slight increase in the unemployment rate fits the pattern observed internationally. It is a minor trade-off when considering the positive growth effects.

Unsurprisingly, and again in line with the international experience, we see a drop in poverty and inequality in all scenarios. The percentage of the population defined as poor is as much as 2.6 percentage points lower than the 37.3% in the baseline scenario.

We should recall that income disparity (and not unemployment) is the main driver of inequality. Minimum wages have been shown to also push up wages for those earning close to, but above the minimum, so the effect on inequality is likely to be greater than shown.

Finally, there is scant empirical evidence, and none offered by Nattrass and Seekings, that low wages will assist SA in boosting growth and reducing poverty, inequality and unemployment. The persistence of low real wages and rising unemployment in the past two decades suggests the opposite.

The national minimum was promised by the government and the ANC, if set at a level above the current (often low) sectoral minima, has the potential to reduce inequality and poverty and boost growth in the economy.

Do we need to be prudent in the design of a national minimum wage? Yes. Are the doom-and-gloom predictions of Nattrass and Seekings credible? No.

• Isaacs is the co-ordinator of the National Minimum Wage Research Initiative at Corporate Strategy and Industrial Development, in the school of economics and business sciences at the University of the Witwatersrand.

Change: 1.19%

Change: 1.36%

Change: 2.19%

Change: 1.49%

Change: -0.77%

Data supplied by Profile Data

Change: -0.08%

Change: 0.12%

Change: 1.19%

Change: 0.00%

Change: 0.10%

Data supplied by Profile Data

Change: 0.32%

Change: 0.36%

Change: 0.33%

Change: 0.22%

Change: 0.23%

Data supplied by Profile Data

Change: -0.04%

Change: -0.51%

Change: -0.25%

Change: -0.17%

Change: -0.02%

Data supplied by Profile Data