PRESIDENT Jacob Zuma is no stranger to court, but in February and March, two cases will be heard that could have significant personal consequences for him. After more than six years of legal wrangling, the court case that could lead to Mr Zuma facing corruption charges once again has finally been set down to be heard in March.

The so-called "spy tapes" case, in which the Democratic Alliance (DA) seeks to have the 2009 decision to drop corruption charges against Mr Zuma reversed, will be heard by a full high court bench in Pretoria on March 1 to 3.

When former acting national director of public prosecutions Mokotedi Mpshe announced his decision to drop the charges against Mr Zuma, he read out excerpts from what later became known as the "spy tapes" — intercepted phone conversations between former National Prosecuting Authority (NPA) head Bulelani Ngcuka and former Scorpions boss Leonard McCarthy.

The tapes seemed to show that Mr Ngcuka and Mr McCarthy had colluded on the timing of the indictment of African National Congress (ANC) president Zuma to influence the outcome of the party’s 2007 elective conference in Polokwane.

Mr Mpshe said the abuse of the legal process was "so gravely wrong" and such a "gross neglect of the elementary principles of fairness", that it would be "unconscionable" for a trial to continue. But the DA’s case is that his decision was irrational and unconstitutional, and that nothing revealed in the tapes affected the quality of the case against Mr Zuma.

After a marathon six-year preliminary battle for access to the documents on which the decision was made including the transcripts of the spy tapes, they were finally handed over to the DA.

The NPA’s case, backed up by the president, is that the prosecuting authority was so riddled with improper political interference that the prosecution of Mr Zuma was fatally tainted. In an explosive affidavit, deputy national director of public prosecutions Willie Hofmeyr laid bare the full extent of the political meddling in the NPA in the run-up to Polokwane. He submitted that Mr McCarthy’s manipulation meant the decision around when to bring the indictment, was taken for an "ulterior purpose". The courts have said that a prosecutor’s motive for a prosecution, even if it is terrible, is irrelevant if there is a case to answer. However, an ulterior purpose is a different matter.

Former Supreme Court of Appeal deputy president Louis Harms held that it would be unlawful for the prosecution to use its power for an "ulterior purpose". This meant "evidence that the prosecution of Mr Zuma was not intended to obtain a conviction", Judge Harms said.

So a prosecution would have been unlawful only if its purpose was never to convict Mr Zuma.

There are at least two hurdles the NPA will have to overcome if it is to succeed in its argument. One is that when Mr Mpshe announced his decision, he went out of his way to say the shenanigans had not affected Mr Zuma’s right to a fair trial. The second is that, in law, the decision to prosecute, as well as when to prosecute, are two, discrete legal acts. Even if the timing of the prosecution was for an ulterior purpose, it does not necessarily mean the decision itself was bad.

If the DA gets its way, the court would not only set aside the decision to withdraw charges, but also order that they be reinstated. But even if a court were to find that the decision to drop charges was unlawful, it will only step into the shoes of the decision-maker in exceptional circumstances. The court could also order that the decision be taken again — properly and lawfully.

Then there is the big Constitutional Court date, set down for February 9, over Public Protector Thuli Madonsela’s report on security upgrades to the president’s private home in Nkandla.

In two separate cases, the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) and the DA want the Constitutional Court to order Mr Zuma to implement Ms Madonsela’s directives including paying back a portion of the reasonable costs for nonsecurity upgrades.

Mr Zuma rode out the storm over the decision to drop corruption charges, but the Nkandla issue remains a hot potato. However, much will depend on whether the two parties are granted leave to approach the highest court. The Constitutional Court has only granted them an audience: to explain why the case warrants leapfrogging the lower courts.

The EFF’s case is that this is one of exclusive jurisdiction: because it involves failures by the president and Parliament to fulfil constitutional obligations.

The DA’s case was originally brought in the high court. But when the EFF was granted an audience by the Constitutional Court, the DA applied for "conditional" direct access. It said if the Constitutional Court were to give direct access to the EFF, it would be in the interests of justice for the court to hear its case at the same time.

February’s hearing might see both the opposition parties sent packing to the high court. But if the Constitutional Court does decide to hear the cases, it could mean a speedy resolution to the opposition’s demands for the president to pay back the money.

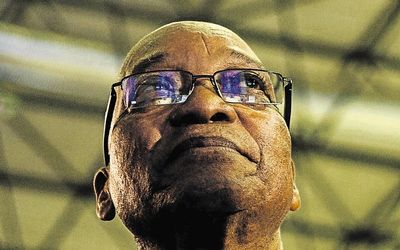

COURT DATES: The ‘spy tapes’ and ‘pay back the money’ matters, in which president Zuma is embroiled, come up in the new year. Picture: SUNDAY TIMES

PRESIDENT Jacob Zuma is no stranger to court, but in February and March, two cases will be heard that could have significant personal consequences for him. After more than six years of legal wrangling, the court case that could lead to Mr Zuma facing corruption charges once again has finally been set down to be heard in March.

The so-called "spy tapes" case, in which the Democratic Alliance (DA) seeks to have the 2009 decision to drop corruption charges against Mr Zuma reversed, will be heard by a full high court bench in Pretoria on March 1 to 3.

When former acting national director of public prosecutions Mokotedi Mpshe announced his decision to drop the charges against Mr Zuma, he read out excerpts from what later became known as the "spy tapes" — intercepted phone conversations between former National Prosecuting Authority (NPA) head Bulelani Ngcuka and former Scorpions boss Leonard McCarthy.

The tapes seemed to show that Mr Ngcuka and Mr McCarthy had colluded on the timing of the indictment of African National Congress (ANC) president Zuma to influence the outcome of the party’s 2007 elective conference in Polokwane.

Mr Mpshe said the abuse of the legal process was "so gravely wrong" and such a "gross neglect of the elementary principles of fairness", that it would be "unconscionable" for a trial to continue. But the DA’s case is that his decision was irrational and unconstitutional, and that nothing revealed in the tapes affected the quality of the case against Mr Zuma.

After a marathon six-year preliminary battle for access to the documents on which the decision was made including the transcripts of the spy tapes, they were finally handed over to the DA.

The NPA’s case, backed up by the president, is that the prosecuting authority was so riddled with improper political interference that the prosecution of Mr Zuma was fatally tainted. In an explosive affidavit, deputy national director of public prosecutions Willie Hofmeyr laid bare the full extent of the political meddling in the NPA in the run-up to Polokwane. He submitted that Mr McCarthy’s manipulation meant the decision around when to bring the indictment, was taken for an "ulterior purpose". The courts have said that a prosecutor’s motive for a prosecution, even if it is terrible, is irrelevant if there is a case to answer. However, an ulterior purpose is a different matter.

Former Supreme Court of Appeal deputy president Louis Harms held that it would be unlawful for the prosecution to use its power for an "ulterior purpose". This meant "evidence that the prosecution of Mr Zuma was not intended to obtain a conviction", Judge Harms said.

So a prosecution would have been unlawful only if its purpose was never to convict Mr Zuma.

There are at least two hurdles the NPA will have to overcome if it is to succeed in its argument. One is that when Mr Mpshe announced his decision, he went out of his way to say the shenanigans had not affected Mr Zuma’s right to a fair trial. The second is that, in law, the decision to prosecute, as well as when to prosecute, are two, discrete legal acts. Even if the timing of the prosecution was for an ulterior purpose, it does not necessarily mean the decision itself was bad.

If the DA gets its way, the court would not only set aside the decision to withdraw charges, but also order that they be reinstated. But even if a court were to find that the decision to drop charges was unlawful, it will only step into the shoes of the decision-maker in exceptional circumstances. The court could also order that the decision be taken again — properly and lawfully.

Then there is the big Constitutional Court date, set down for February 9, over Public Protector Thuli Madonsela’s report on security upgrades to the president’s private home in Nkandla.

In two separate cases, the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) and the DA want the Constitutional Court to order Mr Zuma to implement Ms Madonsela’s directives including paying back a portion of the reasonable costs for nonsecurity upgrades.

Mr Zuma rode out the storm over the decision to drop corruption charges, but the Nkandla issue remains a hot potato. However, much will depend on whether the two parties are granted leave to approach the highest court. The Constitutional Court has only granted them an audience: to explain why the case warrants leapfrogging the lower courts.

The EFF’s case is that this is one of exclusive jurisdiction: because it involves failures by the president and Parliament to fulfil constitutional obligations.

The DA’s case was originally brought in the high court. But when the EFF was granted an audience by the Constitutional Court, the DA applied for "conditional" direct access. It said if the Constitutional Court were to give direct access to the EFF, it would be in the interests of justice for the court to hear its case at the same time.

February’s hearing might see both the opposition parties sent packing to the high court. But if the Constitutional Court does decide to hear the cases, it could mean a speedy resolution to the opposition’s demands for the president to pay back the money.

Change: 0.60%

Change: 0.63%

Change: 0.47%

Change: 0.73%

Change: 0.27%

Data supplied by Profile Data

Change: 0.30%

Change: -0.41%

Change: 0.60%

Change: 0.00%

Change: -0.46%

Data supplied by Profile Data

Change: 0.54%

Change: 0.98%

Change: 0.68%

Change: 0.99%

Change: -0.23%

Data supplied by Profile Data

Change: -0.56%

Change: -1.78%

Change: -0.73%

Change: -2.48%

Change: -2.20%

Data supplied by Profile Data