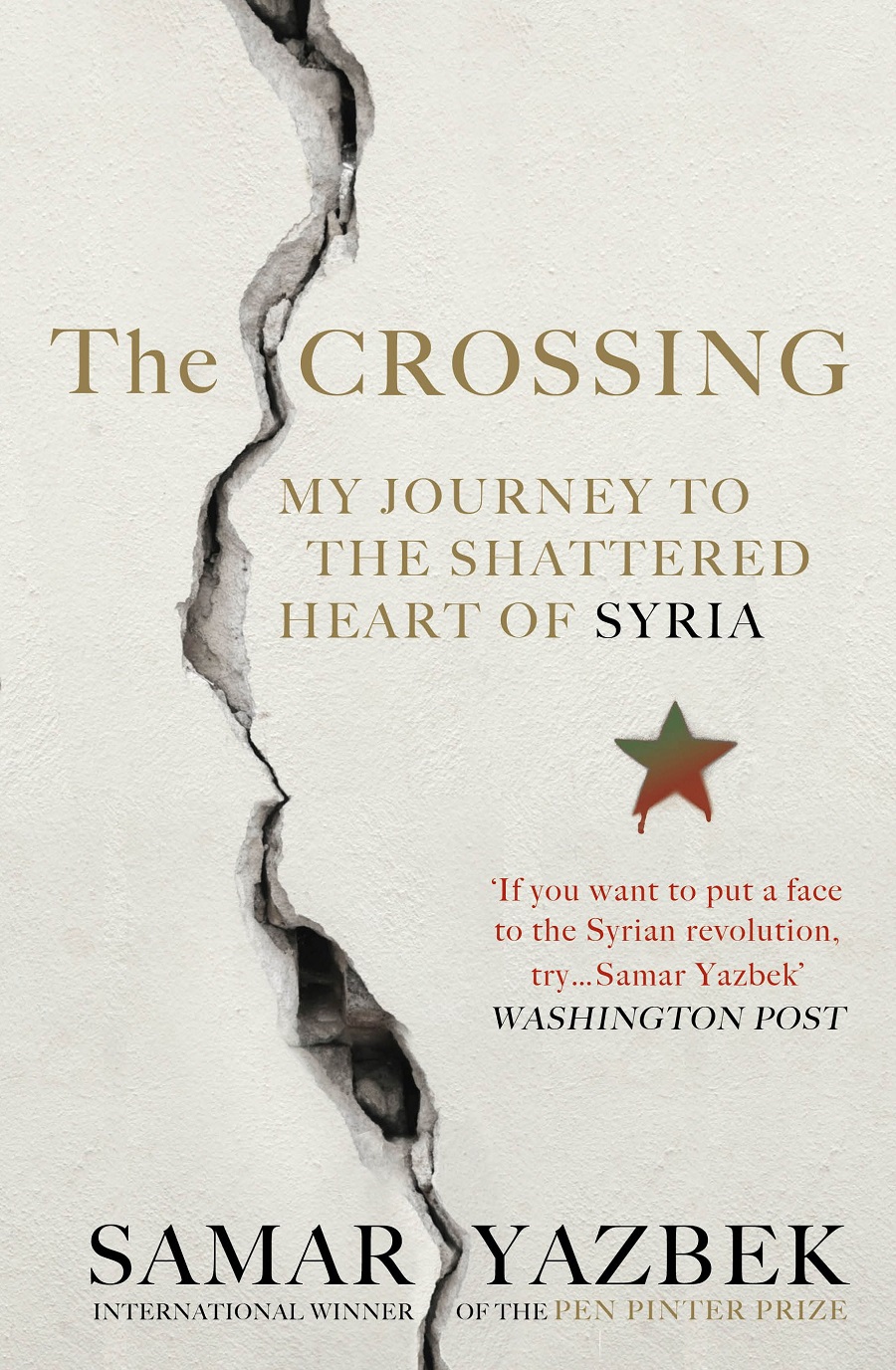

BOOK REVIEW: The Crossing: My Journey to the Heart Of Syria

by Rehana Rossouw,

2015-09-25 06:55:31.0

IN SYRIA millions of people’s lives, homes and livelihoods have been destroyed. Hundreds of thousands of abject refugees are streaming out to neighbouring countries and Europe. Since the start of the war in 2011 more than 250,000 Syrians have died — inside the country and on their way out — as Aylan Kurdi’s body on a beach will forever testify.

Samar Yazbek travels in the opposite direction, crawling under the barbed wire on the border with Turkey, lacerating her back on her way into Syria. The journalist and writer went to set up projects to help women, especially widows, earn a living and record a war with no end in sight.

She was forced into exile in July 2011 and now lives in France with her daughter. She had taken part in demonstrations at the start of the revolution and written articles exposing the intelligence service’s murder and torture, setting them onto her.

Yazbek wrote her first book, A Woman in the Crossfire, about the early days of the Syrian war; The Crossing is her account of her return to Syria in 2012 and 2013.

She makes careful notes of the stories shared by the heartbroken, fearful and violent people she encounters, collecting hundreds of first-hand accounts of lives under siege. They are all united in their grief that they have been abandoned by the world.

Yazbek provides no history of the country, the politics that dragged it into war, of the halting talks about talks that make no progress or of the insurgent movements burying Syria under rubble. Her chosen task is to keep a keen eye on the people suffering in decaying towns and villages and a keen ear on the shelling as the bombs rain down.

Throughout the book, she wrestles with the best way to describe the devastation she encounters during her three crossings into Syria.

She quickly discounts the possibility of a chronological account or an analysis of every event she witnesses.

She allows herself very little room for a collapse in the face of death trapped in rubble. "You simply have to walk up to tiny fingers and gather them up from the rubble. Just pull out the body of another child, her clothes still warm from her urine. And then move on to the next site and carry on searching for more victims.

"You must forget the faces of the victims so you can write about them later, so you can tell their stories and narrate to the outside world how their eyes shine as they watch the sky that showers us with barrel bombs and deadly gifts.

"It makes no difference if you are capable of analysing what is happening … what matters is that you stand up proud and strong as the sky hails down barrel and cluster bombs, nailing you to the spot with fear."

On her second visit, Yazbek sees that "cemeteries began to live among the people, another everyday part of life like the shops and the streets that wind between the houses. Death was so straightforward here, so close and intimate, it lingered even closer than the breath we breathed."

A woman recounts how her relationship with her husband changed before he died.

"So much death … it brings with it so much love."

Yazbek describes the changes inside the country in the short months between her second and third visit. She visits Raqqa in the north, where she had grown up in a tolerant town reading Virginia Woolf and wishing she was Mrs Dalloway. It is now the headquarters of Islamic State, and residents there warn of floggings and beheadings.

There are shortages of everything: bread, rice, tea, sugar, schooling, health services, clean water to wash her face.

Yet the projects Yazbek supports are on their feet: volunteers tour the country, bringing education to children who haven’t seen a classroom in years; journalists risk kidnapping and death to tell the story of Syria, and markets set up when the all-clear is given, so people can prepare meals to share with visiting strangers.

"We carried on with life, regardless. Families plodded on, eking out a living under the lethal sky, among the barbarism of the extremist battalions," Yazbek writes of what she witnessed. "All the same, the only victor in Syria is death: no one talks of anything else. Everything is relative and open to doubt; the only certainty is that death will triumph."

Yazbek is pessimistic and mournful about the prospect of the world’s conscience being pricked into action on Syria.

"Other people are dying instead of them. They are the survivors and that’s enough. What’s happening is nothing new in the history of humanity, but now it’s unfurling in public view, the blood spilling before our eyes and into our hands.

"We consume the news and then toss it out into the rubbish. This is what the Syrians have become in four years."

'We carried on with life, regardless. Families plodded on, eking out a living under the lethal sky, among the barbarism of the extremist battalions,' Samar Yazbek writes in her book about returning to Syria. Picture: REUTERS

IN SYRIA millions of people’s lives, homes and livelihoods have been destroyed. Hundreds of thousands of abject refugees are streaming out to neighbouring countries and Europe. Since the start of the war in 2011 more than 250,000 Syrians have died — inside the country and on their way out — as Aylan Kurdi’s body on a beach will forever testify.

Samar Yazbek travels in the opposite direction, crawling under the barbed wire on the border with Turkey, lacerating her back on her way into Syria. The journalist and writer went to set up projects to help women, especially widows, earn a living and record a war with no end in sight.

She was forced into exile in July 2011 and now lives in France with her daughter. She had taken part in demonstrations at the start of the revolution and written articles exposing the intelligence service’s murder and torture, setting them onto her.

Yazbek wrote her first book, A Woman in the Crossfire, about the early days of the Syrian war; The Crossing is her account of her return to Syria in 2012 and 2013.

She makes careful notes of the stories shared by the heartbroken, fearful and violent people she encounters, collecting hundreds of first-hand accounts of lives under siege. They are all united in their grief that they have been abandoned by the world.

Yazbek provides no history of the country, the politics that dragged it into war, of the halting talks about talks that make no progress or of the insurgent movements burying Syria under rubble. Her chosen task is to keep a keen eye on the people suffering in decaying towns and villages and a keen ear on the shelling as the bombs rain down.

Throughout the book, she wrestles with the best way to describe the devastation she encounters during her three crossings into Syria.

She quickly discounts the possibility of a chronological account or an analysis of every event she witnesses.

She allows herself very little room for a collapse in the face of death trapped in rubble. "You simply have to walk up to tiny fingers and gather them up from the rubble. Just pull out the body of another child, her clothes still warm from her urine. And then move on to the next site and carry on searching for more victims.

"You must forget the faces of the victims so you can write about them later, so you can tell their stories and narrate to the outside world how their eyes shine as they watch the sky that showers us with barrel bombs and deadly gifts.

"It makes no difference if you are capable of analysing what is happening … what matters is that you stand up proud and strong as the sky hails down barrel and cluster bombs, nailing you to the spot with fear."

On her second visit, Yazbek sees that "cemeteries began to live among the people, another everyday part of life like the shops and the streets that wind between the houses. Death was so straightforward here, so close and intimate, it lingered even closer than the breath we breathed."

A woman recounts how her relationship with her husband changed before he died.

"So much death … it brings with it so much love."

Yazbek describes the changes inside the country in the short months between her second and third visit. She visits Raqqa in the north, where she had grown up in a tolerant town reading Virginia Woolf and wishing she was Mrs Dalloway. It is now the headquarters of Islamic State, and residents there warn of floggings and beheadings.

There are shortages of everything: bread, rice, tea, sugar, schooling, health services, clean water to wash her face.

Yet the projects Yazbek supports are on their feet: volunteers tour the country, bringing education to children who haven’t seen a classroom in years; journalists risk kidnapping and death to tell the story of Syria, and markets set up when the all-clear is given, so people can prepare meals to share with visiting strangers.

"We carried on with life, regardless. Families plodded on, eking out a living under the lethal sky, among the barbarism of the extremist battalions," Yazbek writes of what she witnessed. "All the same, the only victor in Syria is death: no one talks of anything else. Everything is relative and open to doubt; the only certainty is that death will triumph."

Yazbek is pessimistic and mournful about the prospect of the world’s conscience being pricked into action on Syria.

"Other people are dying instead of them. They are the survivors and that’s enough. What’s happening is nothing new in the history of humanity, but now it’s unfurling in public view, the blood spilling before our eyes and into our hands.

"We consume the news and then toss it out into the rubbish. This is what the Syrians have become in four years."

Change: 2.98%

Change: 3.39%

Change: 2.94%

Change: 3.00%

Change: 5.00%

Data supplied by Profile Data

Change: 2.19%

Change: 1.38%

Change: 2.98%

Change: 0.00%

Change: 1.97%

Data supplied by Profile Data

Change: -0.51%

Change: 0.04%

Change: -1.31%

Change: -1.43%

Change: -0.58%

Data supplied by Profile Data

Change: -0.44%

Change: 1.41%

Change: -0.64%

Change: 0.36%

Change: 7.03%

Data supplied by Profile Data