THE National Development Plan is official policy of government. That message is being hammered home through every key political speech that is made. Almost as soon as it was written in 2012, it was officially adopted by cabinet. The 2014 elections served to entrench it within the ANC’s manifesto. The new cabinet has been given the NDP as the key guide to government business over the next five years.

President Jacob Zuma in his State of the Nation speech in June described the NDP as key to government’s programme of action. Finance Minister Nhlanhla Nene, in his medium-term budget speech in August, said budgeting was based on aiming to meet the aims of the NDP. Jeff Radebe, the Minister in the Presidency responsible for planning, monitoring and evaluation, also said in August: “The message is very clear: the NDP train left the station in 2012 and is now moving at a very high speed.”

That train has morphed into the medium-term-strategic framework (MTSF), the critical guide for government business over the next five years, which describes itself as the “first five-year implementation phase of the NDP”.

The rhetoric is clearly aimed at quelling political disquiet over the NDP. That disquiet has come largely from the alliance’s left-wing flank which has expressed the most consistent opposition, at least regarding the NDP’s economic aspects. But the ramrodding of the policy has been consistent. It has served to establish ANC policy as supreme in the alliance with Cosatu and the SA Communist Party.

That is a major shift from Zuma’s first term, when labour and other leftist concerns were given prominence. Then the crowd-pleasing tactic was to declare that any policy was up for debate, from nationalisation to labour regulations. Zuma’s second term has struck a remarkably different note: the time for debate is over. The NDP is policy and it will be implemented.

Labour strife

This stance has fed tensions within the alliance. Cosatu’s internal strife, which threatens to tear apart the organisation, is directly linked to the NDP.

The ANC, in an effort to calm SA’s destructive labour relations environment, has tried to act as peace maker, with deputy President Cyril Ramaphosa recently tasked with attempting to unite Cosatu. Labour has a new policy focus: a national minimum wage. Labour indabas held in September and November by the National Economic Development and Labour Council (Nedlac) focused on minimum wages as a potential avenue for labour to gain some traction on policy. At the September event, Ramaphosa was at pains to calm fears over the NDP, saying: “There is no way any social partner can be left behind in our effort to achieve the objectives of the NDP.” Yet on areas where there is agreement, he said implementation would forge ahead.

Despite its strong opposition, Cosatu was all but ignored on the issue of the youth wage subsidy, an NDP-backed policy that has now been implemented. Already, according to Nene, 200,000 young people are being employed because of it, far in excess of government’s initial expectation of 70,000 after six months.

The youth wage subsidy was clearly still a sore point at the indaba, with Cosatu President Sdumo Dlamini saying that he remained worried about policies “if you insist on ramming them down on us without our contribution”. He said various aspects of the NDP remained a concern within the federation.

The internecine battles in Cosatu are only likely to weaken the federation’s ability to affect policy. As this publication was going to press, the probability that a major part of the federation would split off with the National Union of Metalworkers of SA into a new political formation was high. Numsa, which in May told its members not to vote for the ANC, has accused the ruling party of no longer being “pro-worker”. Numsa now looks set to take several of Cosatu’s constituent unions with it into a new grouping that will stand opposed to the ANC, possibly alongside other formations such as the Economic Freedom Fighters and the Association of Mining and Construction Union (Amcu) which spearheaded the platinum sector strikes.

Numsa has been the most vocal critic of the NDP within the labour movement, declaring a year ago to the ANC that it was “us or the NDP”. It insisted that the NDP was “right wing” and in conflict with the Freedom Charter. It now seems set to follow through on its threat.

A divided labour movement would be less able to affect the NDP at policy level, but can stand in the way of implementation. With government rhetoric clear that the NDP is no longer up for negotiation, the response of labour has been internal political chaos. The NDP emphasises partnership between various constituencies to meet its objectives. As the highly damaging strikes in the platinum sector and metals sector this year showed, the growth objectives of the NDP can clearly be undermined. The ANC knows it is important to ensure that labour is a willing partner, but has also presented a show of strength in forging ahead with policy. It faces a dilemma of its own: the labour movement clearly delivers votes for it, but the government’s failure to drive economic growth and employment is losing it votes. Clearly the latter view is in the ascendency as the party increasingly worries about holding onto its election majority.

Running out of options

While the ANC was quick to downplay the impact of rating agency Moody’s downgrade of South Africa’s sovereign debt in November, it was a painful public indictment of the state of the economy and its prospects. “It is a problem. We are already in a bad shape on many fronts and the downgrade will make it more difficult especially to borrow. So we are in a difficult situation,” says a long-time senior bureaucrat.

The downgrade had long been expected, but Nene had attempted as far as possible to calm the nerves of ratings agencies in his medium-term budget policy statement, which emphasised curbing fiscal spending and hinted at tax increases for the first time since 1994. The downgrades have a direct effect on government’s ability to deliver aspects of the NDP that require it to raise debt on international markets. The downgrades increase the cost as buyers demand increased returns for the higher risk they are taking on. Fitch, another agency, has SA on a negative ratings watch and could well downgrade the country in December.

Moody’s reasoning included “poor medium-term growth prospects due to structural weaknesses, including ongoing energy shortages as well as rising interest rates, further deterioration in the investor climate and a less supportive capital market environment”. While it praised many aspects of the NDP, it also said the results would be too far off and some interventions are “unproven”.

The rating is now one notch away from junk status, which would make it substantially more expensive for SA to raise foreign debt. There is a sense of panic within government about how the often unbudgeted needs of various parastatals, the normal government budget deficit and the ambitious infrastructure projects of the NDP can all be financed.

The ANC is also worried about its electoral performance, with local government elections due in 2016. Key cities such as Johannesburg and Port Elizabeth are vulnerable with support in those areas having clearly deteriorated in this year’s national elections. With a potentially strong new political formation in the offing on the left, the ANC needs to cement the support of the black middle class. While the NDP pushes for sober, evidence-based policy, so keen has the ANC been on placating that constituency it has forced more radical interventions such the credit information amnesty and amendments to BEE codes that ostensibly please black middle-class voters. The pressure supports implementation of the NDP, but also risks creating political will to overstep into territory that conflicts with it.

But the country’s financial state is unavoidable. The ANC desperately needs economic growth to drive revenue collection and bring down unemployment. Both are essential to its electoral success and the NDP is what it’s hoping will deliver it.

A government within government

The broad ideological church that has been the alliance has often meant competing agendas in government delivery. Under Trevor Manuel and then Pravin Gordhan, National Treasury acted as the constraint on other departments’ policy ambitions which contradicted each other and risked damaging the economy and fiscal position of government. Treasury has a structural advantage as the controlling force over the budget process and monitoring of the financial performance of all other institutions of state. That has earned it the moniker of “government within the government”, as political analyst Richard Calland has put it.

The power of Treasury earned it some strident political opposition from other ministers who complained that it was thwarting their plans. Its attempt to implement economic impact assessments as part of the process of forming legislation showed the limits of its political authority. Departments simply refused to subject themselves to the assessments.

The power of National Treasury was at its apex during Thabo Mbeki’s Presidency with Trevor Manuel at the helm. Under Zuma that power has steadily declined, with first Pravin Gordhan and then Nhlanhla Nene clearly technically proficient but without the weight of political capital Manuel carried. Nene is not a member of the ANC’s National Executive Committee and Gordhan was only added to it halfway to through his term.

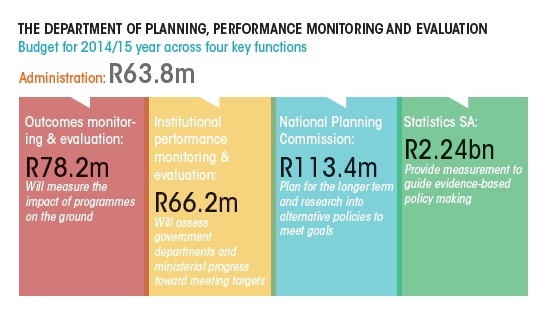

When Manuel moved from Treasury to head up the National Planning Commission as Minister in the Presidency, it marked a shift in power. The Presidency under Zuma has grown in capacity and stature. That is even more so under the new cabinet. It has centralised all planning as well as the monitoring and implementation of the NDP. With Manuel having left politics after this year’s election, the power of the Department of Planning, Monitoring and Evaluation (DPME), as it is now called, is led by Radebe, one of the longest-serving ministers in government who has the full backing of the President. This has included a restructuring within the Presidency, with the NDP secretariat now being consolidated into a single department with the older functions of monitoring and evaluation.

This creates a new “government within government”. The DPME will play a key oversight role over the rest of government with the implementation of the NDP being its prime agenda. The next five years’ business of government is reflected in the MTSF which has assigned particular responsibilities to individual departments.

The President is, according to Radebe, entering into performance agreements with all ministers based on the roles, responsibilities and targets in the MTSF (these are summarised in section 2 of this special report). National Treasury clearly still has its oversight role in ensuring money is well managed, but its overreach into issues like impact assessments has now moved squarely into the realm of the DPME. It is a government within government that previous detractors of the Treasury version are likely to find tougher.

Naturally the Presidency depends for its legitimacy on the authority of Zuma. With Zuma’s credibility battered by the Nkandla saga and lingering corruption allegations related to the arms deal, his political weight alone is not sufficient to drive the NDP. That is why it is key to see it as a cabinet-wide policy. It is also why the institutional capacity of the Presidency is important. Effective oversight will go a long way to covering ground the President cannot cover alone.

A new commission

For the National Planning Commission itself, which drew up and delivered the plan in 2012, the future is somewhat less certain. The term of the 26 commissioners comes to an end in April 2015. The commission is still engaged with research. Khulekani Mathe, the acting head of the NDP secretariat, says various research projects are live, such as a pilot programme for land reform initiatives and another to test interventions on youth unemployment.

Ramaphosa, who was deputy chairman to Manuel during the process of developing the plan, is now chairman of the commission with Radebe his deputy. It is assumed a new set of commissioners will be appointed next year and, under Ramaphosa’s guidance, they will have a new planning and research agenda.

It remains to be seen who will be appointed and what its mandate will be. The first raft were appointed by Zuma and drawn from nominations by the public. Clearly Manuel would have played a key role in deciding who made the list, which was dominated by experienced academics and scientists. Given the evidence-based orientation of policy making under the plan, tapping SA’s universities for research skills is likely to remain the approach. But this time, there will be more political contestation given the importance the plan has come to have, which could not have been anticipated back in 2010 when the first commission was appointed.

The ambition is also to entrench planning capacity across government. The commission seems set to play an important ongoing role as a bridge between government and the rest of the research capacity in the country, particularly at universities. Ramaphosa will have the task of conducting this orchestra, with its eyes focused 20 years into the future.

Change: -0.47%

Change: -0.61%

Change: 0.53%

Change: -0.42%

Change: -2.12%

Data supplied by Profile Data

Change: -0.46%

Change: -0.19%

Change: -0.47%

Change: 0.00%

Change: -0.16%

Data supplied by Profile Data

Change: -1.11%

Change: -1.07%

Change: -0.63%

Change: -1.21%

Change: -1.24%

Data supplied by Profile Data

Change: 0.52%

Change: 1.25%

Change: 1.31%

Change: 0.18%

Change: 1.12%

Data supplied by Profile Data