EDUCATION: School upgrades making a difference

by Johann Barnard ,

2014-11-20 07:01:31.0

“WITH THIS PROJECT, dignity has been given back to our learners — that is the most important thing that has changed,” comments Margot Kiewiet, principal of Die Duine Primary school on the Cape Flats in Western Cape. “There has been a huge change in terms of the learners’ and teachers’ attitudes to teaching, and seeing the learners in the classroom has brought about a change that shows what education is all about.”

Die Duine is one of 25 schools being replaced in the province under the national education department’s Accelerated School Infrastructure Delivery Initiative (ASIDI).

“Our school consisted of pre-fabricated buildings that have a lifespan of 15 years, so after 40 years they were dilapidated and not conducive to teaching. In summer it was extremely hot, and in winter they were very cold.

“What we have at the moment they specialised classrooms; hopefully we will become an arts and culture-focused school with the music and arts rooms, as well as two computer rooms,” Kiewiet says.

The school now also has a school hall that is also available for use by the local community, while the second phase of the reconstruction project is focused on improving school yards and sports facilities.

While stories such as this are becoming more common-place as the Department of Basic Education (DBE) rolls out its school infrastructure programme, many challenges still remain.

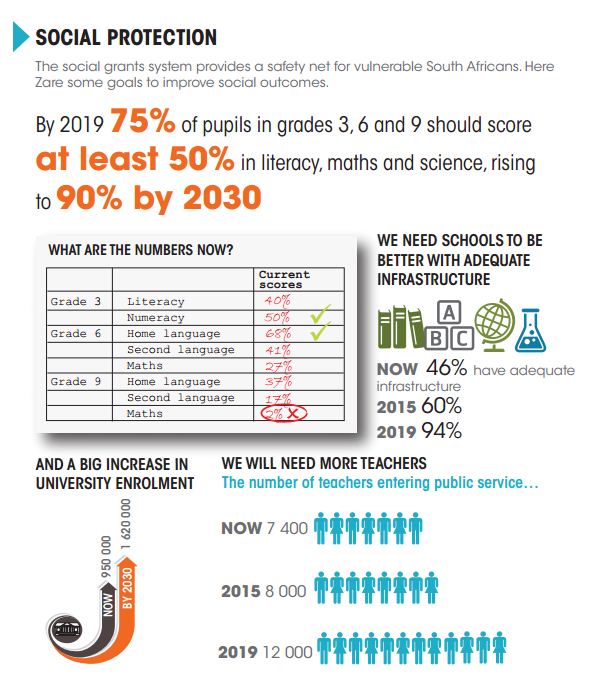

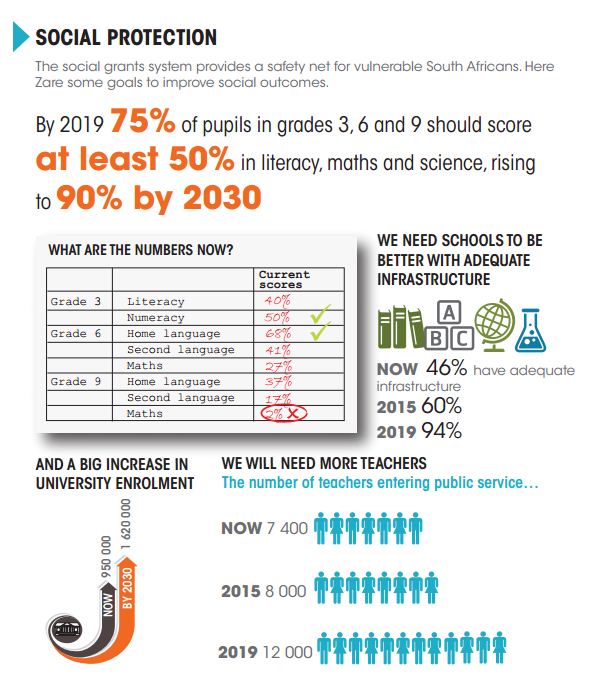

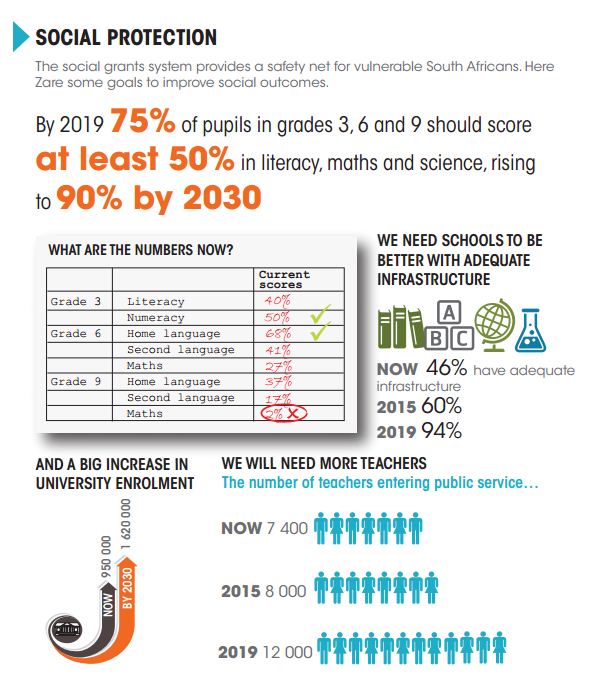

Targets published in the medium-term strategic framework (MTSF) outline two main areas requiring attention. The first is to eradicate “inappropriate” school structures, such as those at Die Duine, and to build new structures with adequate facilities.

It then also says that 60% of schools should comply with the DBE’s norms and standards by the end of this financial year. The baseline was 46% compliance in 2011. The target for 2018/19 is 94%.

The department was compelled to publish legally binding Norms and Standards for School Infrastructure at the end of 2013 after NGO Equal Education dragged the minister to court following her failure to do so.

These guidelines for the first time dictate that every school must have water, electricity, Internet access, working toilets, safe classrooms with a maximum of 40 learners, security, and thereafter libraries, laboratories and sports facilities.

It would appear that actual numbers and levels of compliance depend on who you speak to.

The Centre for Child Law published a report in August this year in which it lambasted the Department of Basic Education (DBE) for inaccuracies and contradictions in its reports on infrastructure projects.

More concerning was its finding that the department has underspent its School Infrastructure Backlog in 2011/2012 (spending little more than 10%) and only 23% by the third quarter of 2012/2013. The result was that only 10 of the 49 schools targeted for those years were built.

Eradicating unsuitable conditions at schools around the country is clearly a challenge. What is evident though is that it is making a tangible difference at schools where the department has managed to do so.

“If this is the way government is moving forward, our education will change in a few years time,” Kiewiet comments. “The children want to be here and there is a new pride in the learners and parents. The school is now like an oasis in the community and the whole mindset has changed.”

Picture: THINKSTOCK

“WITH THIS PROJECT, dignity has been given back to our learners — that is the most important thing that has changed,” comments Margot Kiewiet, principal of Die Duine Primary school on the Cape Flats in Western Cape. “There has been a huge change in terms of the learners’ and teachers’ attitudes to teaching, and seeing the learners in the classroom has brought about a change that shows what education is all about.”

Die Duine is one of 25 schools being replaced in the province under the national education department’s Accelerated School Infrastructure Delivery Initiative (ASIDI).

“Our school consisted of pre-fabricated buildings that have a lifespan of 15 years, so after 40 years they were dilapidated and not conducive to teaching. In summer it was extremely hot, and in winter they were very cold.

“What we have at the moment they specialised classrooms; hopefully we will become an arts and culture-focused school with the music and arts rooms, as well as two computer rooms,” Kiewiet says.

The school now also has a school hall that is also available for use by the local community, while the second phase of the reconstruction project is focused on improving school yards and sports facilities.

While stories such as this are becoming more common-place as the Department of Basic Education (DBE) rolls out its school infrastructure programme, many challenges still remain.

Targets published in the medium-term strategic framework (MTSF) outline two main areas requiring attention. The first is to eradicate “inappropriate” school structures, such as those at Die Duine, and to build new structures with adequate facilities.

It then also says that 60% of schools should comply with the DBE’s norms and standards by the end of this financial year. The baseline was 46% compliance in 2011. The target for 2018/19 is 94%.

The department was compelled to publish legally binding Norms and Standards for School Infrastructure at the end of 2013 after NGO Equal Education dragged the minister to court following her failure to do so.

These guidelines for the first time dictate that every school must have water, electricity, Internet access, working toilets, safe classrooms with a maximum of 40 learners, security, and thereafter libraries, laboratories and sports facilities.

It would appear that actual numbers and levels of compliance depend on who you speak to.

The Centre for Child Law published a report in August this year in which it lambasted the Department of Basic Education (DBE) for inaccuracies and contradictions in its reports on infrastructure projects.

More concerning was its finding that the department has underspent its School Infrastructure Backlog in 2011/2012 (spending little more than 10%) and only 23% by the third quarter of 2012/2013. The result was that only 10 of the 49 schools targeted for those years were built.

Eradicating unsuitable conditions at schools around the country is clearly a challenge. What is evident though is that it is making a tangible difference at schools where the department has managed to do so.

“If this is the way government is moving forward, our education will change in a few years time,” Kiewiet comments. “The children want to be here and there is a new pride in the learners and parents. The school is now like an oasis in the community and the whole mindset has changed.”

Change: -0.47%

Change: -0.61%

Change: 0.53%

Change: -0.42%

Change: -2.12%

Data supplied by Profile Data

Change: -0.46%

Change: -0.19%

Change: -0.47%

Change: 0.00%

Change: -0.16%

Data supplied by Profile Data

Change: -1.11%

Change: -1.23%

Change: -0.78%

Change: -1.36%

Change: -1.24%

Data supplied by Profile Data

Change: 0.52%

Change: 1.35%

Change: 1.31%

Change: 0.18%

Change: 1.12%

Data supplied by Profile Data