MONTHS after construction group First Tech collapsed, taking 7,000 jobs and the country’s biggest corporate bond down with it, sensational new court documents reveal how chairman Jeff Wiggill swindled blue-chip lenders out of about R4bn.

First Tech’s demise is the biggest corporate collapse this year and the largest single default in South Africa’s corporate bond market.

It left the big banks — mostly Standard Bank, Investec and Nedbank — red-faced after they enthusiastically subscribed to First Tech’s BBB-rated bond last year, pouring altogether R915m of investors’ cash into the bond in a scramble for yield.

The Industrial Development Corporation (IDC), after losing more than R800m in its investment in Top-TV and R97m in failed BEE jeweller African Romance, was exposed to the First Tech bond to the tune of R123m.

Now, court papers seen by Business Times reveal how Mr Wiggill forged the signature of FirstTech CEO Andy Bertulis, his partner of 20 years, on at least one contract in which the two top executives stood surety for all the company’s debts in their personal capacity.

In a case bearing more than a passing resemblance to the fraud involving the late Brett Kebble, Mr Wiggill was murdered on a dirt road near Soweto in June.

His body was cremated immediately, leading some investigators to believe it wasn’t he who was killed.

But behind closed doors, a legal inquiry was held this month in a bid to establish what happened, and whether anything could be salvaged for the lenders.

In one summons, fuel supplier Masana Petroleum Solutions claimed Mr Bertulis personally owed it just over R3.2m for fuel used by First Strut — the company that traded as First Tech.

Copies of the contract attached to the summons appear to have been signed and initialled by both Mr Bertulis and Mr Wiggill. The two were co-principal debtors on behalf of First Strut, which meant that they had offered up their own worldly belongings as a guarantee that the debts would be met.

However, an apparently shocked Mr Bertulis said this was nonsense. Through his lawyers, Ian Levitt Attorneys, Mr Bertulis denied owing Mansana anything at all.

In his affidavit resisting summary judgment, Mr Bertulis said “the signature is a forgery”.

Michael Strauss, Mr Bertulis’s attorney, said three handwriting analysts had examined the signatures on these documents as well as Mr Bertulis’s own. All these analysts said the signatures on the contract appeared to have been done by the same person.

Mr Strauss said Mr Bertulis was deeply distressed about having been betrayed by his friend and business partner of more than two decades.

He said that while Mr Wiggill was the financial brain, Mr Bertulis was more the face of the company involved with marketing and dealing with clients.

One of the more astonishing aspects of this case is that all the governance systems in place to prevent exactly this kind of fraud, failed.

Andrew Canter, chief investment officer of asset manager Futuregrowth, said all the institutions should bear some blame for this. “So many people were looking out for the red flags (which) the company’s finances should have raised. Analysts, the bond exchange, asset managers, credit agencies, and, above all, the auditors -but no one saw it,” he said.

No official information has been released about how all these systems were short-circuited, but individuals close to the case claim Mr Wiggill forged income statements and accounts to make it appear that the company was functional, and not drowning in a sea of debt.

It now appears that the banks extended credit because the First Tech directors signed surety in their personal capacity.

If Mr Bertulis’s signature was forged it implies that — at least in this one instance — he was not personally complicit in the fraud.

Mr Bertulis, who shared an office with Mr Wiggill at the First Tech head office in Johannesburg’s grimy industrial suburb of Benrose, has long maintained that he knew nothing about what was going on.

In a sworn statement in August applying for Cosira’s liquidation after Mr Wiggill had died, Mr Bertulis said: “The financial affairs of First Strut were solely undertaken by Mr Wiggill who was murdered on Wednesday 19 June 2013.”

As the company’s labyrinthine finances are now being informally reconstructed, the heads of several of the companies inside the First Tech stable say that First Tech was a house of cards held together through creatively accessing credit to fund ballooning debt.

While the corporate bond, listed on the SA Bond Exchange, was one example of this, First Tech raised money repeatedly to buy new subsidiaries to hide massive losses and to fund the lifestyles of Mr Wiggill and Mr Bertulis.

By the time First Tech went bust, it had 18 subsidiaries.

Senior bankers said that Mr Wiggill raised a number of bonds over the same vehicles and machinery many times over — and sometimes even to the same bank — with changed serial numbers.

Leon Kapp, who briefly ran First Tech’s subsidiary Cosira, said the heads of the various subsidiaries were never formally brought together as a board and so they never swapped the stories of their companies’ financial woes.

Eventually, Mr Kapp and three other CEOs held several meetings and established that the financial status of the holding company was unsustainable.

...

But it was too late, and the company came crashing down.

First Tech fraud leaves pensioners in the lurch

THERE is little doubt that the country’s biggest lenders have been swindled royally by years of extensive fraud at First Tech, but the defaulted R925m bond also has nasty implications for ordinary investors — you and me.

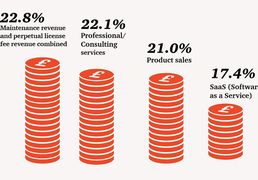

Known as “covenant lite” bonds, corporate bonds offer no protection to investors, while the banks and other lending institutions rarely extend credit without an underlying security such as property or equipment.

The implication is that institutions are willing to leave their pensioners and other investors to the wolves while keeping themselves safe.

Richard Klotnick, fixed-income portfolio manager at Momentum Asset Management, which did not buy into the bond, said that corporate bonds were generally issued to listed behemoths such as Bidvest and Imperial Holdings, which had long track records and were highly rated.

However, First Tech’s bond was rated BBB, the lowest investment grade. Investment in this bond would provide a comparatively high yield -which would make the asset managers look good — but could be risky for those invested.

Worse, because the banks had also lent to the company and their loans were secured, investors were put into a subordinated position: if the company went belly-up, as happened eventually, the banks would be first in line to get their money back after the liquidators had sold the assets.

Futuregrowth chief investment officer Andrew Canter was outspoken about the unethical nature of this structure, saying the banks arranging these deals had in the past eight years been “selling things that they would not themselves buy onto their balance sheet”.

Ultimately though, the extent of the fraud at First Tech has meant that even the banks, which thought they had security, will be left out to dry.

It appears that the security, such as property and equipment, was frequently bonded more than once, meaning there will be many bites at each cherry.

Figures for how much the banks were exposed to the bond are kept a close secret, but some numbers have trickled out.

While figures are available only for Investec (which lent R240m) and the IDC (R123m), Nedbank, Sanlam and Standard Bank were all exposed, as were numerous asset managers.

• This article was first published in Sunday Times: Business Times

OPULENT MANSION: The late Jeff Wiggill's imposing home in Woolston Drive in Westcliff, Johannesburg. Picture: SIMON MATHEBULA/SUNDAY TIMES

MONTHS after construction group First Tech collapsed, taking 7,000 jobs and the country’s biggest corporate bond down with it, sensational new court documents reveal how chairman Jeff Wiggill swindled blue-chip lenders out of about R4bn.

First Tech’s demise is the biggest corporate collapse this year and the largest single default in South Africa’s corporate bond market.

It left the big banks — mostly Standard Bank, Investec and Nedbank — red-faced after they enthusiastically subscribed to First Tech’s BBB-rated bond last year, pouring altogether R915m of investors’ cash into the bond in a scramble for yield.

The Industrial Development Corporation (IDC), after losing more than R800m in its investment in Top-TV and R97m in failed BEE jeweller African Romance, was exposed to the First Tech bond to the tune of R123m.

Now, court papers seen by Business Times reveal how Mr Wiggill forged the signature of FirstTech CEO Andy Bertulis, his partner of 20 years, on at least one contract in which the two top executives stood surety for all the company’s debts in their personal capacity.

In a case bearing more than a passing resemblance to the fraud involving the late Brett Kebble, Mr Wiggill was murdered on a dirt road near Soweto in June.

His body was cremated immediately, leading some investigators to believe it wasn’t he who was killed.

But behind closed doors, a legal inquiry was held this month in a bid to establish what happened, and whether anything could be salvaged for the lenders.

In one summons, fuel supplier Masana Petroleum Solutions claimed Mr Bertulis personally owed it just over R3.2m for fuel used by First Strut — the company that traded as First Tech.

Copies of the contract attached to the summons appear to have been signed and initialled by both Mr Bertulis and Mr Wiggill. The two were co-principal debtors on behalf of First Strut, which meant that they had offered up their own worldly belongings as a guarantee that the debts would be met.

However, an apparently shocked Mr Bertulis said this was nonsense. Through his lawyers, Ian Levitt Attorneys, Mr Bertulis denied owing Mansana anything at all.

In his affidavit resisting summary judgment, Mr Bertulis said “the signature is a forgery”.

Michael Strauss, Mr Bertulis’s attorney, said three handwriting analysts had examined the signatures on these documents as well as Mr Bertulis’s own. All these analysts said the signatures on the contract appeared to have been done by the same person.

Mr Strauss said Mr Bertulis was deeply distressed about having been betrayed by his friend and business partner of more than two decades.

He said that while Mr Wiggill was the financial brain, Mr Bertulis was more the face of the company involved with marketing and dealing with clients.

One of the more astonishing aspects of this case is that all the governance systems in place to prevent exactly this kind of fraud, failed.

Andrew Canter, chief investment officer of asset manager Futuregrowth, said all the institutions should bear some blame for this. “So many people were looking out for the red flags (which) the company’s finances should have raised. Analysts, the bond exchange, asset managers, credit agencies, and, above all, the auditors -but no one saw it,” he said.

No official information has been released about how all these systems were short-circuited, but individuals close to the case claim Mr Wiggill forged income statements and accounts to make it appear that the company was functional, and not drowning in a sea of debt.

It now appears that the banks extended credit because the First Tech directors signed surety in their personal capacity.

If Mr Bertulis’s signature was forged it implies that — at least in this one instance — he was not personally complicit in the fraud.

Mr Bertulis, who shared an office with Mr Wiggill at the First Tech head office in Johannesburg’s grimy industrial suburb of Benrose, has long maintained that he knew nothing about what was going on.

In a sworn statement in August applying for Cosira’s liquidation after Mr Wiggill had died, Mr Bertulis said: “The financial affairs of First Strut were solely undertaken by Mr Wiggill who was murdered on Wednesday 19 June 2013.”

As the company’s labyrinthine finances are now being informally reconstructed, the heads of several of the companies inside the First Tech stable say that First Tech was a house of cards held together through creatively accessing credit to fund ballooning debt.

While the corporate bond, listed on the SA Bond Exchange, was one example of this, First Tech raised money repeatedly to buy new subsidiaries to hide massive losses and to fund the lifestyles of Mr Wiggill and Mr Bertulis.

By the time First Tech went bust, it had 18 subsidiaries.

Senior bankers said that Mr Wiggill raised a number of bonds over the same vehicles and machinery many times over — and sometimes even to the same bank — with changed serial numbers.

Leon Kapp, who briefly ran First Tech’s subsidiary Cosira, said the heads of the various subsidiaries were never formally brought together as a board and so they never swapped the stories of their companies’ financial woes.

Eventually, Mr Kapp and three other CEOs held several meetings and established that the financial status of the holding company was unsustainable.

...

But it was too late, and the company came crashing down.

First Tech fraud leaves pensioners in the lurch

THERE is little doubt that the country’s biggest lenders have been swindled royally by years of extensive fraud at First Tech, but the defaulted R925m bond also has nasty implications for ordinary investors — you and me.

Known as “covenant lite” bonds, corporate bonds offer no protection to investors, while the banks and other lending institutions rarely extend credit without an underlying security such as property or equipment.

The implication is that institutions are willing to leave their pensioners and other investors to the wolves while keeping themselves safe.

Richard Klotnick, fixed-income portfolio manager at Momentum Asset Management, which did not buy into the bond, said that corporate bonds were generally issued to listed behemoths such as Bidvest and Imperial Holdings, which had long track records and were highly rated.

However, First Tech’s bond was rated BBB, the lowest investment grade. Investment in this bond would provide a comparatively high yield -which would make the asset managers look good — but could be risky for those invested.

Worse, because the banks had also lent to the company and their loans were secured, investors were put into a subordinated position: if the company went belly-up, as happened eventually, the banks would be first in line to get their money back after the liquidators had sold the assets.

Futuregrowth chief investment officer Andrew Canter was outspoken about the unethical nature of this structure, saying the banks arranging these deals had in the past eight years been “selling things that they would not themselves buy onto their balance sheet”.

Ultimately though, the extent of the fraud at First Tech has meant that even the banks, which thought they had security, will be left out to dry.

It appears that the security, such as property and equipment, was frequently bonded more than once, meaning there will be many bites at each cherry.

Figures for how much the banks were exposed to the bond are kept a close secret, but some numbers have trickled out.

While figures are available only for Investec (which lent R240m) and the IDC (R123m), Nedbank, Sanlam and Standard Bank were all exposed, as were numerous asset managers.

• This article was first published in Sunday Times: Business Times

Register/Login

Close XMy News

You can only set up or view personalised news headlines when you are logged in as a registered user. Thereafter you can choose the sectors of industry in which you are interested, and the latest articles from those sectors will display in this area of your console.

Login or Register.Top Stories

My Watchlist

You can only set up or view your share watchlist when you are logged in as a registered user. Thereafter you can select a list of companies and enter your share details to monitor their performance.

Login or Register.My Clippings

You can only clip articles when you are logged in as a registered user. Thereafter you can click on the "Read later" icon at the top of an article to save it to this area of your console, where you can return to read it at any time.

Login or Register.Change: -1.21%

Change: -1.31%

Change: -1.11%

Change: -1.12%

Change: -2.16%

Data supplied by Profile Data

Change: 0.00%

Change: 0.00%

Change: -1.21%

Change: 0.00%

Change: 0.00%

Data supplied by Profile Data

Change: 0.01%

Change: 0.05%

Change: 0.07%

Change: -0.09%

Change: -0.19%

Data supplied by Profile Data

Change: 0.00%

Change: 0.00%

Change: 0.00%

Change: 0.00%

Change: 0.00%

Data supplied by Profile Data