PULLING up in his white Mercedes sports utility vehicle, Liu Youbin shouts over the din of the shopping mall construction site where Chinese supervisors watch over a couple of dozen Zambian workers.

But Liu can’t hide his pessimism. Plans for the mall were drafted five years ago, he says, when Zambia’s economy was roaring. "Before, everything was great," he says. "Now, we lose money every day."

For more than a decade, Zambia offered prime evidence of Africa’s rise, its soaring economy propelled by China’s seemingly insatiable appetite for its copper. Deepening ties brought new roads, hospitals and stadiums, all built by the Chinese.

But China’s economic slowdown has caused Zambia’s economy to tumble. Thousands of jobs have been lost, and Zambia recently held a national day of prayer to revive its currency.

The quick downturn in recent months in many of Africa’s fastest-growing economies suggests how much of the impressive growth in the past decade-and-a-half was still driven by a boom in commodities — one supercharged by China.

Now, China’s demand for raw materials has cooled, as it tries to shift its economy away from construction, investment and exports to one driven by consumption and services. That transformation is already jolting countries in Africa, from those with diversified economies, such as SA, to those dependent on a single export, such as Zambia or Angola, even as the Chinese government and businesses express long-term commitment to the continent.

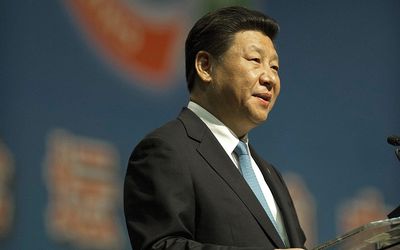

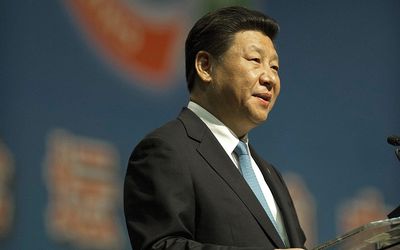

At the China-Africa forum in Johannesburg last week, China’s President Xi Jinping announced plans to help bolster industrialisation and manufacturing. Chinese businesses are still investing in Zambia and elsewhere. SA recently said China had pledged $50bn to help it industrialise.

"It’s going to be interesting to see how much capacity, strength or will China has towards Africa during this period," says Ross Anthony, acting director of the Centre for Chinese Studies at Stellenbosch University. "If they play it right and show commitment irrespective of their own domestic issues, that could really cement relations between China and Africa, because there are many people in Africa who are still sitting on the fence."

In the Copperbelt of Zambia, two mines have closed in recent weeks. Six thousand jobs have been lost.

But the shock was compounded by the fact that one of the mines had a Chinese owner, the China Nonferrous Metals Company.

"People expected China, or Chinese companies, to be the last to retrench workers," says Godfrey Hampwaye, an economic geographer at the University of Zambia. "People thought China was Africa’s best friend."

As China’s demand for commodities has diminished — helping to bring down the worldwide prices of everything from copper to coal, diamonds and gold — many other African governments are confronting yawning holes in their budgets.

Some previously high-flying, commodity-dependent countries— such as Zambia, Angola and Ghana — have borrowed heavily from international creditors in recent months.

With creditors now demanding higher interest rates, the debt load of some African nations has increased.

The continent’s two biggest economies, Nigeria and SA, are slowing down.

In Zambia, as well as in many other African countries, there are few signs that governments used the profits from the commodities boom to diversity their economies, and to make them less dependent on foreign investors and less subject to cycles of boom and bust.

Copper, which makes up more than 70% of Zambia’s exports, is now worth less than half of its peak price just a few years ago.

"The time for reckoning has come, because we have been putting all our eggs in one basket," says Nkole Chishimba, president of the Zambia Congress of Trade Unions. "Zambia, since independence in 1964, has talked about the need to diversify beyond copper, and we have just missed another great opportunity to do that," he says.

Zambia could have used revenues from the copper boom to develop other areas, such as agriculture and tourism, Chishimba and others say.

Some Chinese say they will keep doing business as Zambia rides out its slump.

"Long term, this place is still a good investment," says Liu.

During China’s economic modernisation, the government ensured companies seeking to do business in China including in the copper industry in Jiangxi, transferred skills and technology.

But Zambia and other African countries appear to have failed to benefit broadly from the commodities boom in China, whether by not negotiating better terms with Chinese companies, not insisting on technology transfers or not using the revenues from raw materials to diversify their economies.

"We have to look inwards as sub-Saharan Africa," says Kryticous Nshindano, executive director of the Civil Society for Poverty Reduction Zambia.

"Is it an issue of leadership, institutions, corruption? We know what we’re supposed to do, but why are we not doing what we’re supposed to do?" he asks.

New York Times

Despite a slowdown in the Chinese economy that is hurting Africa, President Xi Jinping announced plans to boost industrialisation and manufacturing during the China-Africa forum. Picture: AFP PHOTO/MUJAHID SAFODIEN

PULLING up in his white Mercedes sports utility vehicle, Liu Youbin shouts over the din of the shopping mall construction site where Chinese supervisors watch over a couple of dozen Zambian workers.

But Liu can’t hide his pessimism. Plans for the mall were drafted five years ago, he says, when Zambia’s economy was roaring. "Before, everything was great," he says. "Now, we lose money every day."

For more than a decade, Zambia offered prime evidence of Africa’s rise, its soaring economy propelled by China’s seemingly insatiable appetite for its copper. Deepening ties brought new roads, hospitals and stadiums, all built by the Chinese.

But China’s economic slowdown has caused Zambia’s economy to tumble. Thousands of jobs have been lost, and Zambia recently held a national day of prayer to revive its currency.

The quick downturn in recent months in many of Africa’s fastest-growing economies suggests how much of the impressive growth in the past decade-and-a-half was still driven by a boom in commodities — one supercharged by China.

Now, China’s demand for raw materials has cooled, as it tries to shift its economy away from construction, investment and exports to one driven by consumption and services. That transformation is already jolting countries in Africa, from those with diversified economies, such as SA, to those dependent on a single export, such as Zambia or Angola, even as the Chinese government and businesses express long-term commitment to the continent.

At the China-Africa forum in Johannesburg last week, China’s President Xi Jinping announced plans to help bolster industrialisation and manufacturing. Chinese businesses are still investing in Zambia and elsewhere. SA recently said China had pledged $50bn to help it industrialise.

"It’s going to be interesting to see how much capacity, strength or will China has towards Africa during this period," says Ross Anthony, acting director of the Centre for Chinese Studies at Stellenbosch University. "If they play it right and show commitment irrespective of their own domestic issues, that could really cement relations between China and Africa, because there are many people in Africa who are still sitting on the fence."

In the Copperbelt of Zambia, two mines have closed in recent weeks. Six thousand jobs have been lost.

But the shock was compounded by the fact that one of the mines had a Chinese owner, the China Nonferrous Metals Company.

"People expected China, or Chinese companies, to be the last to retrench workers," says Godfrey Hampwaye, an economic geographer at the University of Zambia. "People thought China was Africa’s best friend."

As China’s demand for commodities has diminished — helping to bring down the worldwide prices of everything from copper to coal, diamonds and gold — many other African governments are confronting yawning holes in their budgets.

Some previously high-flying, commodity-dependent countries— such as Zambia, Angola and Ghana — have borrowed heavily from international creditors in recent months.

With creditors now demanding higher interest rates, the debt load of some African nations has increased.

The continent’s two biggest economies, Nigeria and SA, are slowing down.

In Zambia, as well as in many other African countries, there are few signs that governments used the profits from the commodities boom to diversity their economies, and to make them less dependent on foreign investors and less subject to cycles of boom and bust.

Copper, which makes up more than 70% of Zambia’s exports, is now worth less than half of its peak price just a few years ago.

"The time for reckoning has come, because we have been putting all our eggs in one basket," says Nkole Chishimba, president of the Zambia Congress of Trade Unions. "Zambia, since independence in 1964, has talked about the need to diversify beyond copper, and we have just missed another great opportunity to do that," he says.

Zambia could have used revenues from the copper boom to develop other areas, such as agriculture and tourism, Chishimba and others say.

Some Chinese say they will keep doing business as Zambia rides out its slump.

"Long term, this place is still a good investment," says Liu.

During China’s economic modernisation, the government ensured companies seeking to do business in China including in the copper industry in Jiangxi, transferred skills and technology.

But Zambia and other African countries appear to have failed to benefit broadly from the commodities boom in China, whether by not negotiating better terms with Chinese companies, not insisting on technology transfers or not using the revenues from raw materials to diversify their economies.

"We have to look inwards as sub-Saharan Africa," says Kryticous Nshindano, executive director of the Civil Society for Poverty Reduction Zambia.

"Is it an issue of leadership, institutions, corruption? We know what we’re supposed to do, but why are we not doing what we’re supposed to do?" he asks.

New York Times

Change: -1.04%

Change: -1.17%

Change: -1.77%

Change: -0.53%

Change: -2.66%

Data supplied by Profile Data

Change: 0.00%

Change: 0.00%

Change: -1.04%

Change: 0.00%

Change: 0.00%

Data supplied by Profile Data

Change: 0.46%

Change: 0.45%

Change: 0.80%

Change: 0.75%

Change: 0.22%

Data supplied by Profile Data

Change: 0.00%

Change: 0.00%

Change: 0.00%

Change: 0.00%

Change: 0.00%

Data supplied by Profile Data