ALEX Thomson-Payan arrived in Angola in 2007 armed with a business degree from Babson College in Boston and $200,000 raised from Swiss and American friends.

Today the 29-year-old runs Thomson Group International, which earns monthly revenue of more than $2m selling cellphones and supplying oil explorers with services.

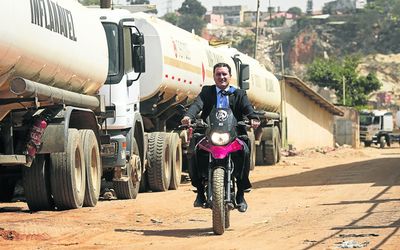

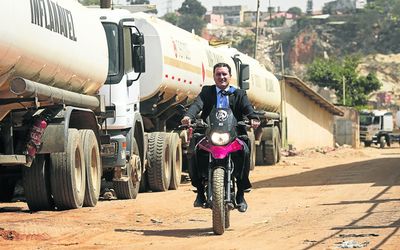

On top of a schedule from dawn to late into the night, he hosts parties at a beachfront house and collects motorcycles.

All this in a country whose civil war ended 12 years ago and which the World Bank ranks among the most difficult for doing business.

Entrepreneurs like Mr Thomson-Payan are becoming more common in Angola, which is attracting investment from Diageo, General Electric, Spar and China’s TBEA.

The country, Africa’s largest crude oil producer after Nigeria, has rebuilt a $1.9bn railway line to the Democratic Republic of Congo as part of $109bn in spending since 2002 on hydroelectric dams, airports, roads and ports, according to the International Monetary Fund.

"The perception of risk is a result of Angola’s headline news reputation, as opposed to the actuality one finds on the ground," Mr Thomson-Payan says. "The result for those who do have a local partner is amazing investment opportunities that benefit from high returns."

When the civil war ended in 2002, the capital Luanda, a city of almost 6-million, sported buildings pockmarked by shell fire and had only two or three serviceable hotels, on a sewage-filled bay. Today it boasts a skyline rivalling that of Africa’s biggest business centre, and a string of expensive restaurants and hotels along a palm-fringed spit extending into the Atlantic.

Investors are still hindered by obstacles in getting work permits for foreign workers and a cost of living that makes Luanda the world’s most expensive city for expatriates, according to Mercer. The 2014 World Bank ease of doing business index ranks Angola 179th of 189 countries, below Nigeria and Zimbabwe. It is at 153 out of 177 on Transparency International’s 2013 corruption perceptions index.

The World Bank estimates the population of Angola at 21-million and the United Nations says more than half live on less than $1.25 a day, Even so, the capital boasts restaurants that charge as much as $85 a hamburger, sports cars are not uncommon and the bay is lined with yachts.

The election victory of the ruling Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA) in 2012 was marred by protests in Luanda and a police crackdown on opponents.

The economy, sub-Saharan Africa’s third-largest, expanded by 6.8% in 2012 to $114bn, according to the World Bank. It was expected to grow 5.1% last year, President Jose Eduardo dos Santos said in October.

Inflation was 8.16% in December, according to the National Statistics Institute.

"Executives who only see challenges in Angola because the business culture is difficult to understand will miss out on a market that has many needs, the ability to pay for things and (which) provides high returns on investment," says Washington-based Frontier Strategy Group ’s senior analyst for sub-Saharan Africa, Anna Rosenberg,

Mr Thomson-Payan began by forming Electrix Telecommunicacoes to manufacture and sell cellphones, including a unit with a 30-day battery.

He distributed them through 25 stores, 20 of them in Luanda, and expanded to become the country’s largest phone distributor by offering other retailers stock financing in exchange for a share in their businesses.

It was not plain sailing at first. He had few contacts at the country’s airport and in 2008 his first three shipments, worth about $80,000 each, were delayed by red tape and looted.

"When I finally found them, 75% had been broken into, it was as if rats had eaten away at the cardboard and pulled out all the phones," he said. "It made me find a solution: someone goes onto the plane and escorts our merchandise directly to our protected area."

Another young entrepreneur, Rupert Wetterings, 25, used $250,000 raised from friends and family in South Africa and the UK to transform his company, Fides Mediador de Seguros, also known as AIBA, into the market’s largest insurance broker.

Mr Wetterings, who has a degree in management and finance from the University of Birmingham, England, said the company had gross written premiums of $30m last year, mostly from oil and gas clients.

"Angola is an exciting and challenging investment destination for those who have an abundance of enthusiasm," he says. "The start was very difficult, but through working very long hours and attracting the right people, we’ve been able to build up the business."

Mr Wetterings benefited as the government acted to weaken the control of state-run companies AAA and Empresa Nacional de Seguros e Resseguros de Angola on the insurance market. In November, Groupe Saham, a Morocco-based investment company, paid an undisclosed amount for GA Angola Seguros, Angola’s largest closely held insurance company by revenue, to gain access to Angola’s $1bn-a-year insurance market.

Companies such as Chevron, Total and BP helped the country pump 1.74-million barrels of oil a day in December, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

Oil exploration and production in Angola attracts an estimated $20bn a year in investment, according to London-based GlobalData and Oilfield Support Angola.

A Diageo spokesman says wealth from the country’s oil industry is propelling sales for the world’s biggest distiller, in premium brands Johnnie Walker Blue Label and Ciroc vodka. Diageo has plans to set up a distribution company in Angola for its Johnnie Walker whisky and Guinness beer, James Crampton says.

South African retailer Spar is supplying merchandise to an Angolan partner in a store under the Savemor brand, called Kamba locally, that opened in December in Luanda, finance director Mark Godfrey says. The first fully fledged Spar-branded store is to open in the northern oil district of Cabinda before April, he says.

Foreign investment this year in Angolan industries excluding oil was $1.9bn by the end of September, compared with $2.3bn for all of 2012, Maria Luisa Abrantes, chairwoman of the National Private Investment Agency, said on October 1.

The agency was targeting $4bn a year in investment outside petroleum as the government sought to diversify the economy, she said. Oil accounts for almost all exports and 80% of tax revenue.

Some investors targeting Angola are reaching out to others already on the ground. Mr Thomson-Payan says he has started a consulting sideline to offer advice, a $4bn investment fund offering an 18% return, and trade finance to give newcomers a leg up.

Back among his Vespas and Yamahas near a long cabana and pool below the balconies of his two-storey house, Mr Thomson-Payan recalls he was attracted to the country after a friend said "you have got to check this place out". Like Mr Wetterings, he says the beginning was tough, and he used his US and Latin American heritage as the grandnephew of Colombian president Alfonso Lopez to overcome a "bit of a wall" against foreigners.

Angola, a former Portuguese colony that gained independence in 1975, has mixed ethnicity.

Ties to South America include Brazil, its fifth-largest trade partner, which shipped $1.14bn in goods to the African country in 2012, according to the Association of Brazilian Entrepreneurs and Executives in Angola.

Thomson Group International has also expanded into construction, property and finance. "There’s a big sense of community in Angola: they take care of each other and as soon as you become a true friend, they take care of you," says Mr Thomson-Payan.

"The right document to get stuff out of the port can take weeks — or minutes if you know the right person."

OPPORTUNITY: Thomson Group International CEO Alexander Thomson-Payan rides his motorcycle in Luanda, Angola. Picture: BLOOMBERG

ALEX Thomson-Payan arrived in Angola in 2007 armed with a business degree from Babson College in Boston and $200,000 raised from Swiss and American friends.

Today the 29-year-old runs Thomson Group International, which earns monthly revenue of more than $2m selling cellphones and supplying oil explorers with services.

On top of a schedule from dawn to late into the night, he hosts parties at a beachfront house and collects motorcycles.

All this in a country whose civil war ended 12 years ago and which the World Bank ranks among the most difficult for doing business.

Entrepreneurs like Mr Thomson-Payan are becoming more common in Angola, which is attracting investment from Diageo, General Electric, Spar and China’s TBEA.

The country, Africa’s largest crude oil producer after Nigeria, has rebuilt a $1.9bn railway line to the Democratic Republic of Congo as part of $109bn in spending since 2002 on hydroelectric dams, airports, roads and ports, according to the International Monetary Fund.

"The perception of risk is a result of Angola’s headline news reputation, as opposed to the actuality one finds on the ground," Mr Thomson-Payan says. "The result for those who do have a local partner is amazing investment opportunities that benefit from high returns."

When the civil war ended in 2002, the capital Luanda, a city of almost 6-million, sported buildings pockmarked by shell fire and had only two or three serviceable hotels, on a sewage-filled bay. Today it boasts a skyline rivalling that of Africa’s biggest business centre, and a string of expensive restaurants and hotels along a palm-fringed spit extending into the Atlantic.

Investors are still hindered by obstacles in getting work permits for foreign workers and a cost of living that makes Luanda the world’s most expensive city for expatriates, according to Mercer. The 2014 World Bank ease of doing business index ranks Angola 179th of 189 countries, below Nigeria and Zimbabwe. It is at 153 out of 177 on Transparency International’s 2013 corruption perceptions index.

The World Bank estimates the population of Angola at 21-million and the United Nations says more than half live on less than $1.25 a day, Even so, the capital boasts restaurants that charge as much as $85 a hamburger, sports cars are not uncommon and the bay is lined with yachts.

The election victory of the ruling Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA) in 2012 was marred by protests in Luanda and a police crackdown on opponents.

The economy, sub-Saharan Africa’s third-largest, expanded by 6.8% in 2012 to $114bn, according to the World Bank. It was expected to grow 5.1% last year, President Jose Eduardo dos Santos said in October.

Inflation was 8.16% in December, according to the National Statistics Institute.

"Executives who only see challenges in Angola because the business culture is difficult to understand will miss out on a market that has many needs, the ability to pay for things and (which) provides high returns on investment," says Washington-based Frontier Strategy Group ’s senior analyst for sub-Saharan Africa, Anna Rosenberg,

Mr Thomson-Payan began by forming Electrix Telecommunicacoes to manufacture and sell cellphones, including a unit with a 30-day battery.

He distributed them through 25 stores, 20 of them in Luanda, and expanded to become the country’s largest phone distributor by offering other retailers stock financing in exchange for a share in their businesses.

It was not plain sailing at first. He had few contacts at the country’s airport and in 2008 his first three shipments, worth about $80,000 each, were delayed by red tape and looted.

"When I finally found them, 75% had been broken into, it was as if rats had eaten away at the cardboard and pulled out all the phones," he said. "It made me find a solution: someone goes onto the plane and escorts our merchandise directly to our protected area."

Another young entrepreneur, Rupert Wetterings, 25, used $250,000 raised from friends and family in South Africa and the UK to transform his company, Fides Mediador de Seguros, also known as AIBA, into the market’s largest insurance broker.

Mr Wetterings, who has a degree in management and finance from the University of Birmingham, England, said the company had gross written premiums of $30m last year, mostly from oil and gas clients.

"Angola is an exciting and challenging investment destination for those who have an abundance of enthusiasm," he says. "The start was very difficult, but through working very long hours and attracting the right people, we’ve been able to build up the business."

Mr Wetterings benefited as the government acted to weaken the control of state-run companies AAA and Empresa Nacional de Seguros e Resseguros de Angola on the insurance market. In November, Groupe Saham, a Morocco-based investment company, paid an undisclosed amount for GA Angola Seguros, Angola’s largest closely held insurance company by revenue, to gain access to Angola’s $1bn-a-year insurance market.

Companies such as Chevron, Total and BP helped the country pump 1.74-million barrels of oil a day in December, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

Oil exploration and production in Angola attracts an estimated $20bn a year in investment, according to London-based GlobalData and Oilfield Support Angola.

A Diageo spokesman says wealth from the country’s oil industry is propelling sales for the world’s biggest distiller, in premium brands Johnnie Walker Blue Label and Ciroc vodka. Diageo has plans to set up a distribution company in Angola for its Johnnie Walker whisky and Guinness beer, James Crampton says.

South African retailer Spar is supplying merchandise to an Angolan partner in a store under the Savemor brand, called Kamba locally, that opened in December in Luanda, finance director Mark Godfrey says. The first fully fledged Spar-branded store is to open in the northern oil district of Cabinda before April, he says.

Foreign investment this year in Angolan industries excluding oil was $1.9bn by the end of September, compared with $2.3bn for all of 2012, Maria Luisa Abrantes, chairwoman of the National Private Investment Agency, said on October 1.

The agency was targeting $4bn a year in investment outside petroleum as the government sought to diversify the economy, she said. Oil accounts for almost all exports and 80% of tax revenue.

Some investors targeting Angola are reaching out to others already on the ground. Mr Thomson-Payan says he has started a consulting sideline to offer advice, a $4bn investment fund offering an 18% return, and trade finance to give newcomers a leg up.

Back among his Vespas and Yamahas near a long cabana and pool below the balconies of his two-storey house, Mr Thomson-Payan recalls he was attracted to the country after a friend said "you have got to check this place out". Like Mr Wetterings, he says the beginning was tough, and he used his US and Latin American heritage as the grandnephew of Colombian president Alfonso Lopez to overcome a "bit of a wall" against foreigners.

Angola, a former Portuguese colony that gained independence in 1975, has mixed ethnicity.

Ties to South America include Brazil, its fifth-largest trade partner, which shipped $1.14bn in goods to the African country in 2012, according to the Association of Brazilian Entrepreneurs and Executives in Angola.

Thomson Group International has also expanded into construction, property and finance. "There’s a big sense of community in Angola: they take care of each other and as soon as you become a true friend, they take care of you," says Mr Thomson-Payan.

"The right document to get stuff out of the port can take weeks — or minutes if you know the right person."

Register/Login

Close XMy News

You can only set up or view personalised news headlines when you are logged in as a registered user. Thereafter you can choose the sectors of industry in which you are interested, and the latest articles from those sectors will display in this area of your console.

Login or Register.Top Stories

My Watchlist

You can only set up or view your share watchlist when you are logged in as a registered user. Thereafter you can select a list of companies and enter your share details to monitor their performance.

Login or Register.My Clippings

You can only clip articles when you are logged in as a registered user. Thereafter you can click on the "Read later" icon at the top of an article to save it to this area of your console, where you can return to read it at any time.

Login or Register.Change: -1.21%

Change: -1.31%

Change: -1.11%

Change: -1.12%

Change: -2.16%

Data supplied by Profile Data

Change: 0.00%

Change: 0.00%

Change: -1.21%

Change: 0.00%

Change: 0.00%

Data supplied by Profile Data

Change: -0.21%

Change: -0.11%

Change: -0.10%

Change: -0.09%

Change: -0.38%

Data supplied by Profile Data

Change: 0.00%

Change: 0.00%

Change: 0.00%

Change: 0.00%

Change: 0.00%

Data supplied by Profile Data